Dementia is often thought of as a memory problem, like when an elderly person asks the same questions or misplaces things. In reality, individuals with dementia will not only experience issues in other areas of cognition like learning, thinking, comprehension and judgement, but they may also experience changes in behaviour.

It’s important to understand what dementia is and how it manifests. I didn’t imagine my grandmother’s strange behaviours were an early warning sign of a far more serious condition.

She would become easily agitated if she wasn’t successful at completing tasks such as cooking or baking. She would claim to see a woman around the house even though no woman was really there. She also became distrustful of others and hid things in odd places.

These behaviours persisted for some time before she eventually received a dementia diagnosis.

Cognitive and behavioural impairment

When cognitive and behavioural changes interfere with an individual’s functional independence, that person is considered to have dementia. However, when cognitive and behavioural changes don’t interfere with an individual’s independence, yet still negatively affect relationships and workplace performance, they are referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild behavioural impairment (MBI), respectively.

MCI and MBI can occur together, but in one-third of people who develop Alzheimer’s dementia, the behavioural symptoms come before cognitive decline.

Spotting these behavioural changes, which emerge in later life (ages 50 and over) and represent a persistent change from longstanding patterns, can be helpful for implementing preventive treatments before more severe symptoms arise. As a medical science PhD candidate, my research focuses on problem behaviours that arise later in life and indicate increased risk for dementia.

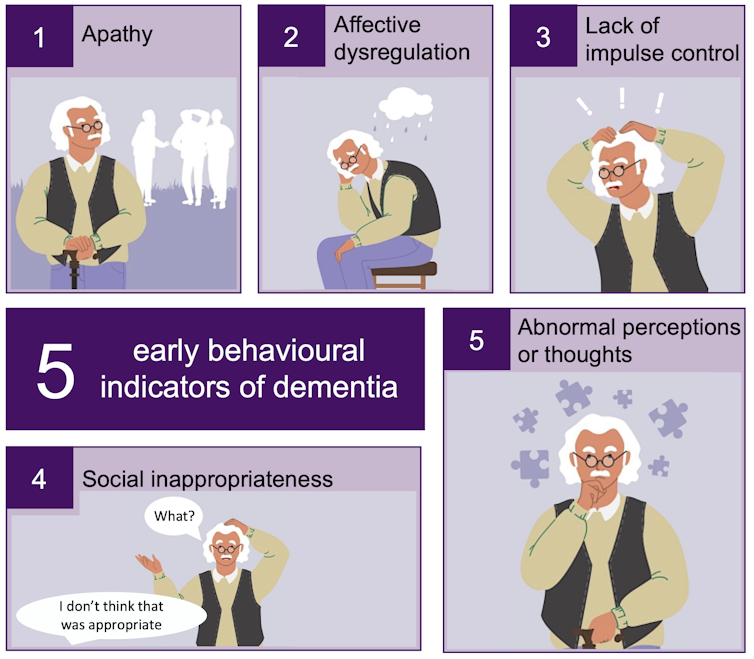

Five behavioural signs to look for

There are five primary behaviours we can look for in friends and family who are over the age of 50 that might warrant further attention.

1. Apathy

Apathy is a decline in interest, motivation and drive.

An apathetic person might lose interest in friends, family or activities. They may lack curiosity in topics that normally would have interested them, lose the motivation to act on their obligations or become less spontaneous and active. They may also appear to lack emotions compared to their usual selves and seem like they no longer care about anything.

2. Affective dysregulation

Affective dysregulation includes mood or anxiety symptoms. Someone who shows affective dysregulation may develop sadness or mood instability or become more anxious or worried about routine things such as events or visits.

3. Lack of impulse control

Impulse dyscontrol is the inability to delay gratification and control behaviour or impulses.

Someone who has impulse dyscontrol may become agitated, aggressive, irritable, temperamental, argumentative or easily frustrated. They may become more stubborn or rigid such that they are unwilling to see other views and are insistent on having their way. Sometimes they may develop sexually disinhibited or intrusive behaviours, exhibit repetitive behaviours or compulsions, start gambling or shoplifting, or experience difficulties regulating their consumption of substances like tobacco or alcohol.

4. Social inappropriateness

Social inappropriateness includes difficulties adhering to societal norms in interactions with others.

Someone who is socially inappropriate may lose the social judgement they previously had about what to say or how to behave. They may become less concerned about how their words or actions affect others, discuss private matters openly, talk to strangers as if familiar, say rude things or lack empathy in interactions with others.

5. Abnormal perceptions or thoughts

Abnormal perception or thought content refers to strongly held beliefs and sensory experiences.

Someone with abnormal perceptions or thoughts may become suspicious of other people’s intentions or think that others are planning to harm them or steal their belongings. They may also describe hearing voices or talk to imaginary people and/or act like they are seeing things that aren’t there.

Before considering any of these behaviours as a sign of a more serious problem, it’s important to rule out other potential causes of behavioural change such as drugs or medications, other medical conditions or infections, interpersonal conflict or stress, or a recurrence of psychiatric symptoms associated with a previous psychiatric diagnosis. If in doubt, it may be time for a doctor’s visit.

The impact of dementia

Many of us know someone who has either experienced dementia or cared for someone with dementia. This isn’t surprising, given that dementia is predicted to affect one million Canadians by 2030.

While people between the ages of 20 and 40 may think that they have decades before dementia affects them, it’s important to realize that dementia isn’t an individual journey. In 2020, care partners — including family members, friends or neighbours — spent 26 hours per week assisting older Canadians living with dementia. This is equivalent to 235,000 full-time jobs or $7.3 billion annually.

These numbers are expected to triple by 2050, so it’s important to look for ways to offset these predicted trajectories by preventing or delaying the progression of dementia.

Identifying those at risk

While there is currently no cure for dementia, there has been progress towards developing effective treatments, which may work better earlier in the disease course.

More research is needed to understand dementia symptoms over time; for example, the online CAN-PROTECT study assesses many contributors to brain aging.

Identifying those at risk for dementia by recognizing later-life changes in cognition, function as well as behaviour is a step towards not only preventing consequences of those changes, but also potentially preventing the disease or its progression.

Daniella Vellone does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.