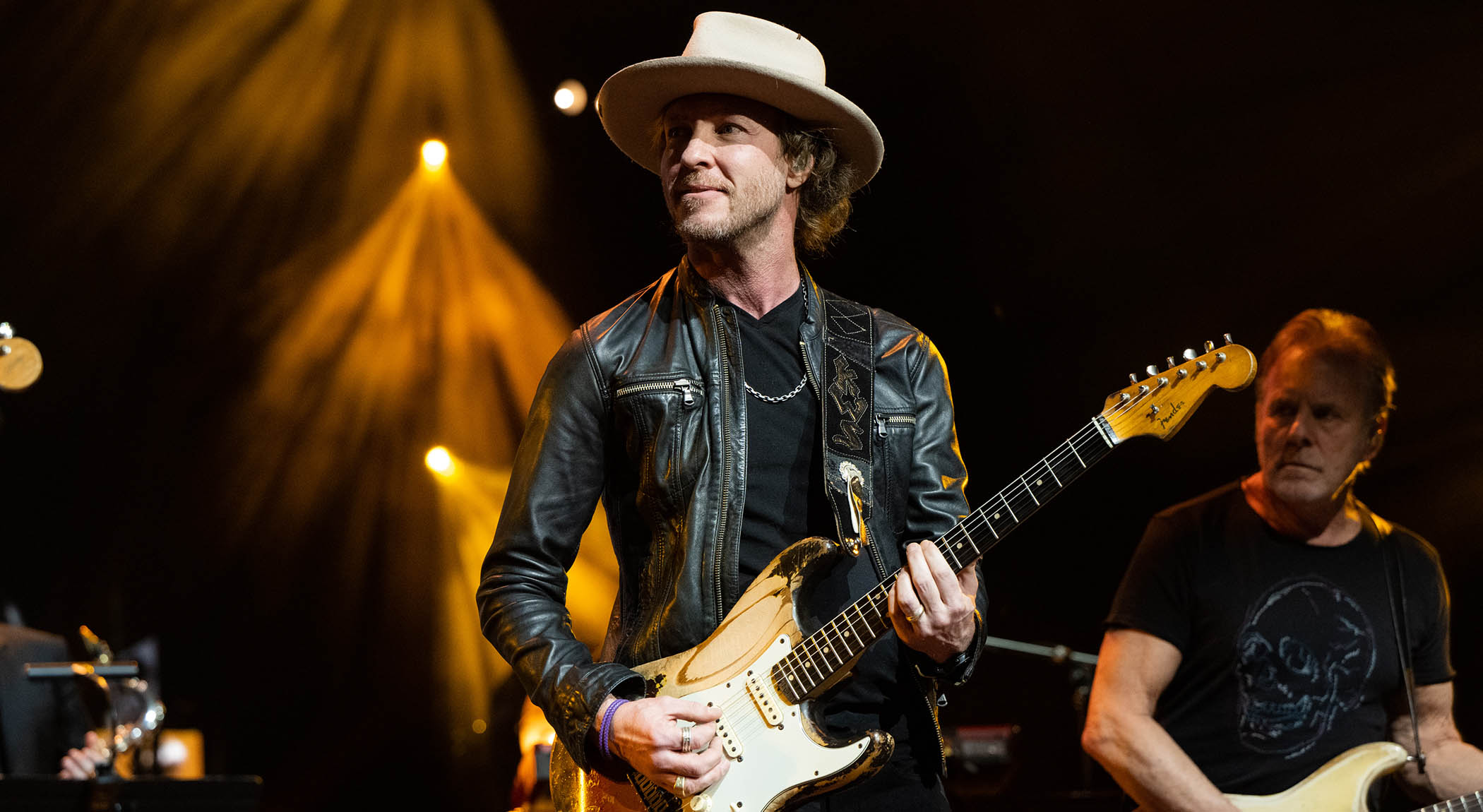

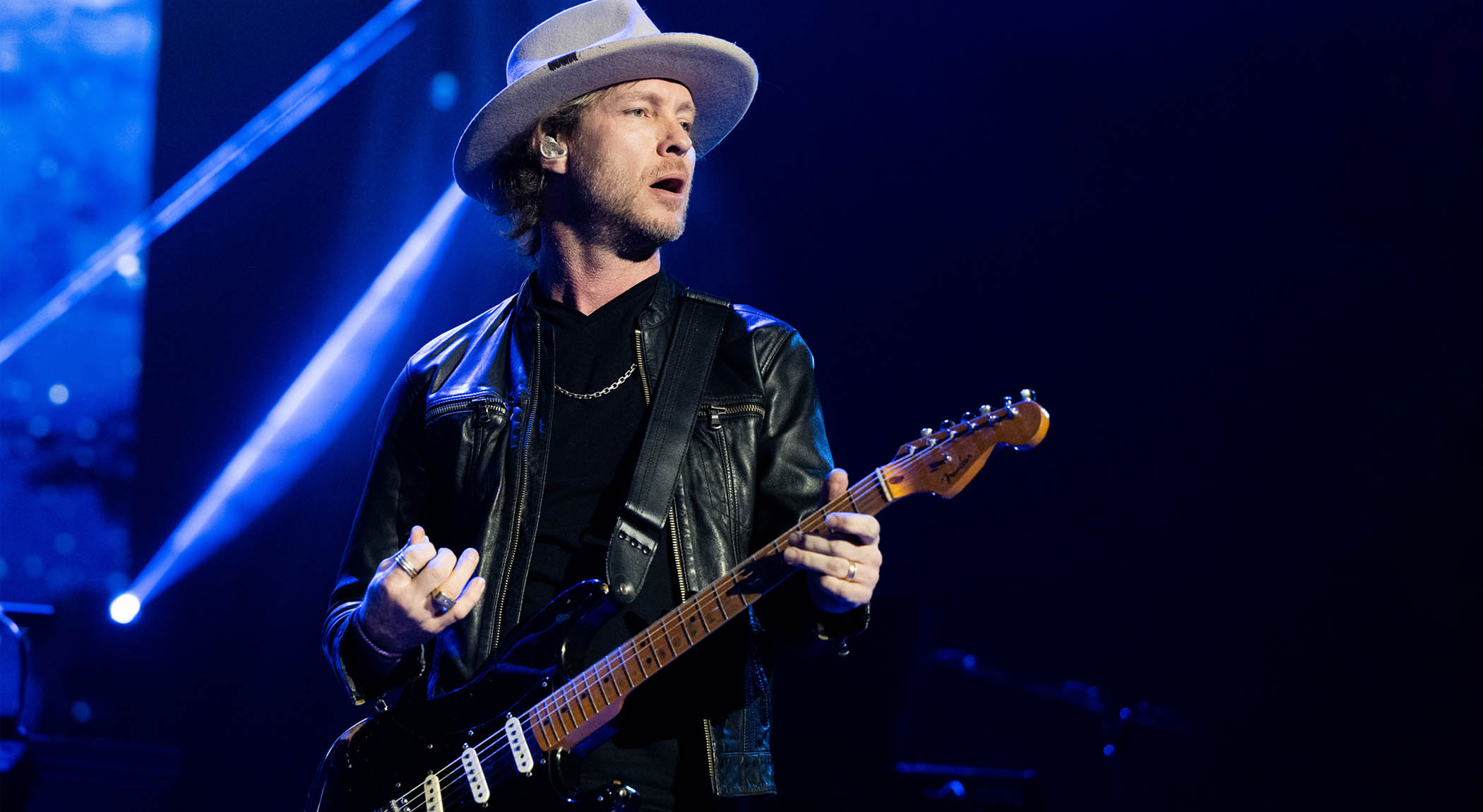

Kenny Wayne Shepherd penned a chunk of his new album Dirt On My Diamonds Vol.2 while soaking up the history of Alabama’s FAME Studios, a place where legends such as Etta James and The Rolling Stones cut records in the past.

Here, the Lousiana-born bluesman discusses his creative process from writing to recording, and explains how the gear addiction he developed as a young player is still as powerful as it ever was…

Your new album Dirt On My Diamonds Vol.2 is the second instalment of a two-volume epic. What was your thinking behind this?

“It really boiled down to me trying to do something different and wanting new ways to engage with my fans. You don’t see many two-volume albums anymore. When I first started recording these songs, I was envisioning two completely separate, unrelated albums. They’re not meant to sound similar, but they were written at the same time.

“We ended Vol.1 with Ease My Mind, which is the most down song on the whole record. It’s back-alley blues, you know? And then you pick up Vol.2 with I Got A Woman, which is a really uplifting and upbeat song. My goal over the past few records has been to project a really optimistic tone. Music is a powerful thing and I want to affect people in a positive way.”

What were the FAME sessions like?

“It’s like walking back in time to when all of those legendary albums were recorded back in the day. It’s an incredible facility. One of the things for me was standing in the vocal booth like, ‘This is where Etta James stood when she was singing’ – she’s one of my all time favourite blues singers. But if you walk into it going, ‘Okay, we’re in Muscle Shoals, this has to affect what we’re doing’, then it’s going to sound contrived. I try to let it happen naturally.

“When I was writing Born With A Broken Heart at my dad’s lake house, a train started rolling down the tracks – and that moment inspired the lyric referring to the blues as a slow rolling train. Your environment is always going to influence what you’re writing, but you can’t force it. The imprint of FAME is definitely on those songs.”

Going back to your beginnings, what was your first guitar?

“My parents bought me a Yamaha SE 150 when I was six or seven. It’s basically a Strat body without the contours. It had one pickup and one volume knob, and it was made out of particle board plywood, and had a Candy Apple Red paint job. It was an incredibly crude guitar.

“My family couldn’t buy me a fancy guitar even if they wanted to. But it was all I needed at the time, to get me going and to really give me an opportunity to start honing on my skills. When you start with a crappy guitar, it begins the cycle of gear addiction.

“You appreciate it, but you long for a better instrument. It gives you a level of appreciation because you started with humble beginnings, and then when you make it to the top of the guitar mountain then you’ve appreciated every step along the way and what it took to get there.”

Is there one guitarist above all others that has had the biggest influence on you?

It’s not just about legends. I had a friend of the family, Tommy Kramer, and he told me how to tune the guitar, stretch the strings and different ways to do vibrato... Fundamental things. He’s just as important as anyone else to me

“I think every great guitar player has heroes and they start by learning to play their heroes’ music. Then, if they’re smart, they start figuring out how to make it your own and not a note-by-note replica of what they did.

“Every legend has had someone that they’ve looked up to and learnt their music as a starting point, like Stevie Ray Vaughan was for me.

“But it’s not just about legends. I had a friend of the family, Tommy Kramer, and he told me how to tune the guitar, stretch the strings and different ways to do vibrato. He showed me fundamental things which a lot of people overlook. They became focal points in my approach to playing guitar and what I do today, so he’s just as important as anyone else to me.”

You spoke of that cycle of gear addiction. Is that still as strong as ever for you?

“I’m always looking for whatever the next thing might be, but the things that have gotten me incredibly, over-the-top excited and influence the music I’m creating are the amplifiers that Alexander Dumble built me before he passed.

“He built 11 different amplifiers over the course of our friendship, and from the first amplifier to the last they elevated my playing and creativity. It freed up so much energy for me to express myself, because I didn’t realise how much energy I was using with my previous amplifiers to try and get them to do the things I wanted them to do.

“There’s something about them that is incredibly revealing about your playing. The transparency is incredible. Some guys won’t like that. But I will officially go on record and say that playing through all of those clones there is no honest comparison. It might get you in the stadium, but you’re nowhere near the ballpark. So if we’re talking about ‘Oh sh*t!’ moments, that one is unbound. How did I live without this stuff before?”

Are you using those amps on the new album?

“I brought them all to the studio, but I’m usually running three to a maximum of five amplifiers at any given time on any given song, and then we’re creating a blend of the best two or three for that particular song. The effects were relatively minimal and very much in my standard wheelhouse.

“There hasn’t been any incredibly groundbreaking developments in the effects world for me, so I have the original versions of all my pedals. I have my Vox Clyde McCoy wah from the ’60s, my original Tycobrahe Octavia, a TS808 Tube Screamer, an Analogue Man King of Tone overdrive, an Analogue Man Bi-chorus pedal.

“And I have an MXR Univibe that allegedly belonged to Jimi Hendrix. There’s also an original ’60s Fuzz Face on Pressure. It had died on me at some point, so Dumble told me to bring it to him because he had a mod he could do to it. It’s the only Dumble Fuzz Face that I’m aware of. It has a really cool sound to it.”

Do you notice a difference with vintage pedals?

“I can hear it. But only a trained ear can hear the differences. In a live environment, are those subtle differences gonna make a difference? Absolutely not. I have no problem using reissue pedals live – by the time it’s gone through speakers, microphones and cables nobody’s gonna notice the difference.”

In terms of technique, are you still learning new tricks?

“My biggest technique that I’ve been honing in on for years, that I feel is more of a fundamental thing than a technique, is: ‘What do I need to do to make you feel something?’ That’s all that matters to me. It’s not like, ‘Am I using this many fingers?’ Or, ‘Am I doing this hybrid picking thing?’”

So what has that quest taught you?

“For me, it’s been discovering the space between the notes and the space within the notes. I’ve learnt to create a space where you normally would feel inclined to fill it to see what that does to the music.

“Does it let the music breathe? Does it give the audience a moment to reflect on what you just played? Does it create tension? And then the space within the notes means holding a note for longer. How long can I hold this note and it still mean something instead of transitioning on to the next thing?

“I’ve found that’s simplified a lot of things I’m doing on stage and in making those subtle changes at the right time, a lot of times the beauty is in the simplicity. It’s created a more emotive experience and a better statement of what I’m doing with my instrument.”

Is it hard to restrain yourself like that?

“Awareness is the first step. It’s a very conscious thing at first but so is everything with the instrument. Like learning a scale until it becomes part of your muscle memory. The hardest thing is identifying where in your music those moments exist and then it’s a lot of trial and error from there.”

I got caught up playing with The Rolling Stones. It was a massive stage and I had a 25ft cable. I took off running and I yanked the cable out of my guitar in the middle of my solo

Have you ever embarrassed yourself onstage?

“I got caught up playing with The Rolling Stones. It was a massive stage and I had a 25ft cable. I took off running and I yanked the cable out of my guitar in the middle of my solo, and then I was having to scurry around to find the cable and plug it back in – in front of 80,000 people! But we’re human. There’s been bad notes. You’ve gotta smile and shake it off. I’ll put it on full display: own it and embrace it. It takes the pressure off.”

And what would you say is your definitive Kenny Wayne Shepherd moment?

“Blue And Black sounds 100 per cent like me, and it was a massive hit. But if you wanted me to give my definition of what contemporary blues is I’d play I Want You from The Traveller. It’s not the most mainstream or successful song, but that’s my definition of modern day blues music. That sound is still evolving and there are still defining moments to be had for me.”

- Dirt on my Diamonds Vol 2 is out now via Mascot/Provogue.