It was a sweet deal. But it came with a catch. The various Cub Scout troops of Monroe County got free tickets to Indiana University football games. And the seats were good ones. We’re talking entire blocks in “the Knothole” behind the Memorial Stadium end zones, just a few feet from the field where you could catch extra points and field goals—often wayward ones, when the home team was doing the kicking.

But in exchange for the tickets, the troops—in a different kind of scout’s honor—had to make a solemn, good-faith promise to stay at the games at least through halftime. Demanding kids remain in the stands for an entire college football game? That was too big an ask. But stay two quarters, stick around for the marching band, and most critically, be there when “official attendance” was tabulated. Then, you were dismissed.

Such was the sad state of Indiana football. Not just in the ’80s, when your intrepid correspondent took advantage of this deal. But for decades upon decades before and after, the Hoosiers were persistent, consistent, insistent losers. You’ve no doubt heard the stat: Entering the 2025 college football season, Indiana was the losingest program in Division I history, more than 700 defeats. But that doesn’t quite paint the dimensions of lousiness.

The last time Indiana—again, we’re talking before this season—had won the Big Ten? It was in 1967, back when the “Big Ten” was truth-in-advertising and there were only nine other teams in the conference. IU traveled to the Rose Bowl and took on USC in what was effectively a home game for the Trojans. USC won 14–3. Their charismatic star running back was the Player of the Game. O.J. Simpson was his name.

In more than a half-century since, Indiana lost early and often, often before oceans of empty seats. They lost by blowout (a 83–20 drubbing at Wisconsin in 2010 comes to mind) and by late-game collapse, stealing defeat from the maw of victory.

If you want a singular, encapsulating low moment, well, you’re spoiled for choices. There was the 1976 game against mighty Ohio State. Indiana scored an early touchdown, an event so momentous that the coach at the time, Lee Corso, burned a timeout to memorialize the occasion, organizing an impromptu team photo in front of the scoreboard, reading Hoosiers 7, Buckeyes 6. (The story became lore, in part because no one seems to have the photo; but last month Corso personally confirmed this account for us.) When the game ended, Indiana still had seven points. Ohio State had hung 47.

In those years, losing was so ritual that Corso leaned into the defeat with gallows humor. On his Sunday postmortem coach’s show, he was known to emerge from a coffin that had been left on the set at the WTTV studios. Corso would then stare at the camera and playfully proclaim, “Baby, we ain’t dead yet.” Then he would break down the grim X’s and O’s. This proved two things: 1) Long before ESPN even existed—never mind the scene-stealing roles on College GameDay—Corso had serious TV chops. 2) College football sure has changed. Imagine a Power 4 coach today, not only lasting season after season with a losing record, but then incorporating the team’s futility into a kind of recurring comedy bit.

Anyway, this was all in keeping with the vibe in Bloomington. Indiana football was so dreadful, you almost had to lean into it and laugh. “Lose the game, win the tailgate,” may as well have been the program’s slogan. John Mellencamp recalls one upside to the losing. A lifelong football fan—as a boy, he was the unofficial mascot of Seymour High School; around then, his uncle played for Indiana—he says that he would go to games starting in the ’70s, have his choice of seats amid the empty rows, and watch his favorite sport, blissfully unbothered.

Eventually fans came. One problem: They were there to cheer on the visitors. Entire fan bases from West Lafayette, Ann Arbor, Columbus and even Iowa City realized that they could convoy to Bloomington and, voilà, it was the equivalent of another home game. (Albeit with better, cheaper seats.) Another low moment: In 1996, Ohio State beat Indiana in Bloomington to clinch a Rose Bowl berth and, emboldened by the sizable Buckeye contingent, tore down one of the goalposts. Indiana players not only lost the game, they then had to stay on the field and play the role of security task force and form a cordon around both end zones. Indiana sent Ohio State a bill for damages, including $1,500 for the goalpost.

The ritual failure at Memorial Stadium was offset by all the ritual winning across the parking lot at Assembly Hall. Football season was like a warmup act for the headliner that was basketball season. When the Hoosiers and their volcanic, meticulous, decidedly un-Corso-like coach, Bob Knight, were winning three NCAA titles in 11 years (1976, 1981 and 1987) well, who cared if the guys wearing pads and helmets were throwing pick-sixes and going 4–7?

Funny thing about it all: Yes, Indiana is most closely associated with hoops. But it’s not as though football was some kind of alien sport. This wasn’t like Alabama having a lousy skiing program. The state of Indiana had long been stocked with football players. Good ones. Five-stars, we’d call them today. Alex Karras, Bob Griese, Rod Woodson, Chris Doleman, Jay Cutler, Jeff George. Hoosiers, all. (It’s just that none went to the state university.) On the north side of the state, Notre Dame has, of course, long been a seminal college program. Even (cough, cough) Purdue was able to recruit the likes of Griese, Len Dawson, Woodson and Drew Brees.

What’s more, in 1984, an NFL franchise decamped from Baltimore in the middle of the night in moving vans, and ended up less than an hour from Bloomington. The Colts resembled the Hoosiers in those early years. That is, they didn’t just lose, but often lost in spectacular and creative ways. (One example among many: coach Rod Dowhower splitting his pants on the sideline midgame and coaching the Colts to defeat shrouded in a towel.) But in time, the Colts drafted Peyton Manning, professionalized the operation, won a Super Bowl and cultivated a rabid football fan base.

Yet none of this football success found its way to Bloomington. And nothing seemed to work. Mellencamp made a seven-figure donation in the ’90s to build an indoor practice facility, hoping it would goose recruiting. (Before this—true story—the team would practice during the week on the field, then paint the grass green before Saturday’s games.) It didn’t help. A series of coaching changes didn’t amount to much either.

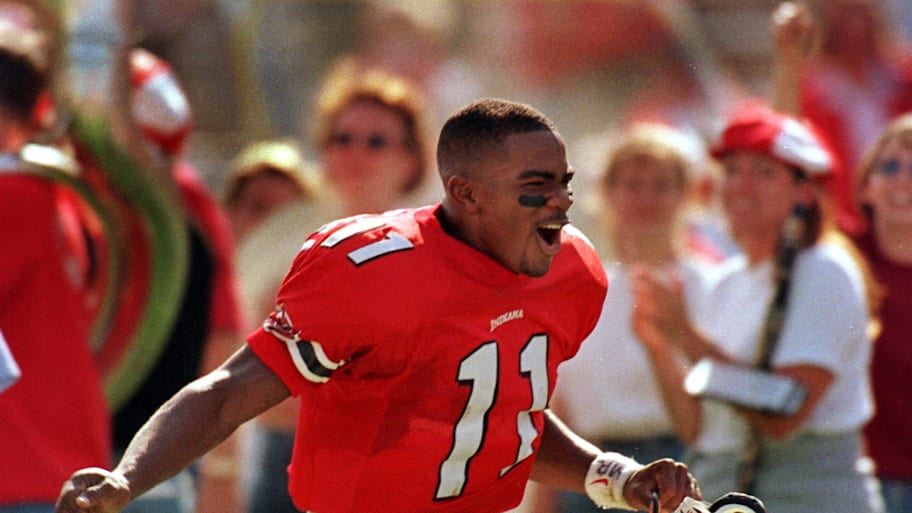

Indiana would develop some fine players, position players in particular. Trent Green. Antwaan Randle El. Anthony Thompson, who nearly (and should have) won the 1989 Heisman Trophy. But undersized O- and D-lines, would prevent success. Other seasons, the lines would hold out. But the quarterbacks couldn’t be counted on to throw a rock in an Indiana quarry.

The most the Hoosiers could muster was a kind of taunting football striptease. That is, Indiana would make a rare bowl appearance in, say, the 1979 Holiday Bowl, winning 38–37 when the BYU kicker missed a chip shot field goal in the waning seconds, leading Corso to practically do cartwheels on the sidelines. Now this thing is moving! Then, the next season the Hoosiers reverted to form and went 3–5 in the Big Ten.

More recently, Indiana looked great during the COVID-19 season of 2020 behind quarterback Michael Penix Jr. He tore his ACL in late November that season, and the following year the Hoosiers fell to 2–10, 0–9 in the Big Ten, and Penix transferred to Washington.

And then in the fall of 2023 … cue the music … one of the great plot points in all of sports, the ultimate flea-flicker. After a typically desultory 3–9 season, the Hoosiers fired head coach Tom Allen, a native Indianan. In the retelling, the school went off the board and made a genius unconventional hire. In truth, Indiana was not going to get the trustees to sign off on a sexy, eight-figure hire (assuming such a candidate would even come to the football boneyard of Bloomington.)

With days to make a hire, Indiana reached out to Curt Cignetti, the 62-year-old head coach of James Madison. “Google me,” would become his catchphrase, of course. But it was no joke. Cignetti’s status was so sufficiently modest that Don Fischer, an Indiana treasure who had been assigned (consigned?) to covering Indiana football since the 1970s had literally never before heard Cignetti’s name. “Really,” he says, “I googled him.”

Cignetti didn’t come alone. He brought his wife, Manette, who, bless her, quickly fell in love with the charms of south central Indiana. He also brought 13 players with him from James Madison, now standard operating procedure under NCAA rules. And this was critical. For one, it showed just how thin the margins are between Power 4 and mid-major talent. A kid who improves technique and puts on some muscle at, say, Kent State or Northern Illinois or Navy can hold his own in the rough-and-tumble Big Ten. And as Indiana became a “portal school,” it became an attractive landing spot for transferring players.

In the first year of the Cignetti era, Indiana went 11–2 and became the darling of college football. The Hoosiers recruited well. They again feasted at the portal, picking up a redshirt junior quarterback from Cal, Fernando Mendoza, whose kid brother was already on the team. Meanwhile Mellencamp was hosting benefits, encouraging wealthy alumni like Mark Cuban to earmark money to the football program and NIL collectives. The school also made sure Cignetti was no flight risk, putting him in the ranks of those eight-figure coaches.

And something funny happened. Instead of regressing as so many IU teams of the past had done, Indiana got even better. The Hoosiers of 2025 won at home, in front of capacity crowds. And on the road, including at Oregon, snapping what had been the longest active home undefeated streak in all of college football. They won in blowouts, perhaps most deliciously, a 56–3 pounding Purdue. They won with their season, literally, on the brink—Mendoza’s late-game touchdown pass to Omar Cooper Jr. against Penn State stands as the play of the year in college football.

And now here we are. The quarterback won the Heisman Trophy, the school’s first winner ever. Cignetti may have grown up in Pennsylvania but his measured sensibilities and mannerisms are pitch perfect for southern Indiana. The Hoosiers are undefeated, ranked No. 1, and fresh off wins against Ohio State and Alabama. It’s hard to exaggerate both the unlikelihood (Indiana beats Alabama? In football? Come on, Grandpa, let’s get you to bed) and the jarring suddenness of it all. And the grim history—the decades of turnovers and penalties and botched kicks and leaving at halftime and small integers on the scoreboard? It makes the current success all the sweeter. Never daunted, indeed.

Two more wins and Indiana is staring at a national championship. And a perfect season … one that, fittingly, comes an even 50 years after the Hoosiers ran the table in hoops (remember hoops?), the last NCAA team to go undefeated.

And then there’s next season. More recruits coming in. More bounty from the transfer portal. Yes, more money from an alumni base—the largest in the country—suddenly swollen with pride over the football program. And if the local Cub Scout troops now have to pay full price for seats inside Memorial Stadium, well, that’s a price of greatness.

More College Football from Sports Illustrated

Listen to SI’s college sports podcast, Others Receiving Votes, below or on Apple and Spotify. Watch the show on SI’s YouTube channel.

- ESPN Analyst Claims Lane Kiffin Has Made Ole Miss 'America's Team'

- Fernando Mendoza Had Deep Answer When Asked What Hype Song He Listens to Before Games

- Miami vs. Ole Miss: Three Bold Predictions for Fiesta Bowl Clash in CFP Semifinal

- Jimbo Fisher Blasts Lane Kiffin for 'Selfish' Decision With Ole Miss Assistants

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Dreadful No More, Curt Cignetti Has Turned Indiana Into a Bona Fide Football School.