The story behind Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece’s paintings ought to be better known than it is – something a new exhibition, ‘Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: An Untold Story’ at Charleston in Lewes (the East Sussex property’s town-centre gallery) aims to put right.

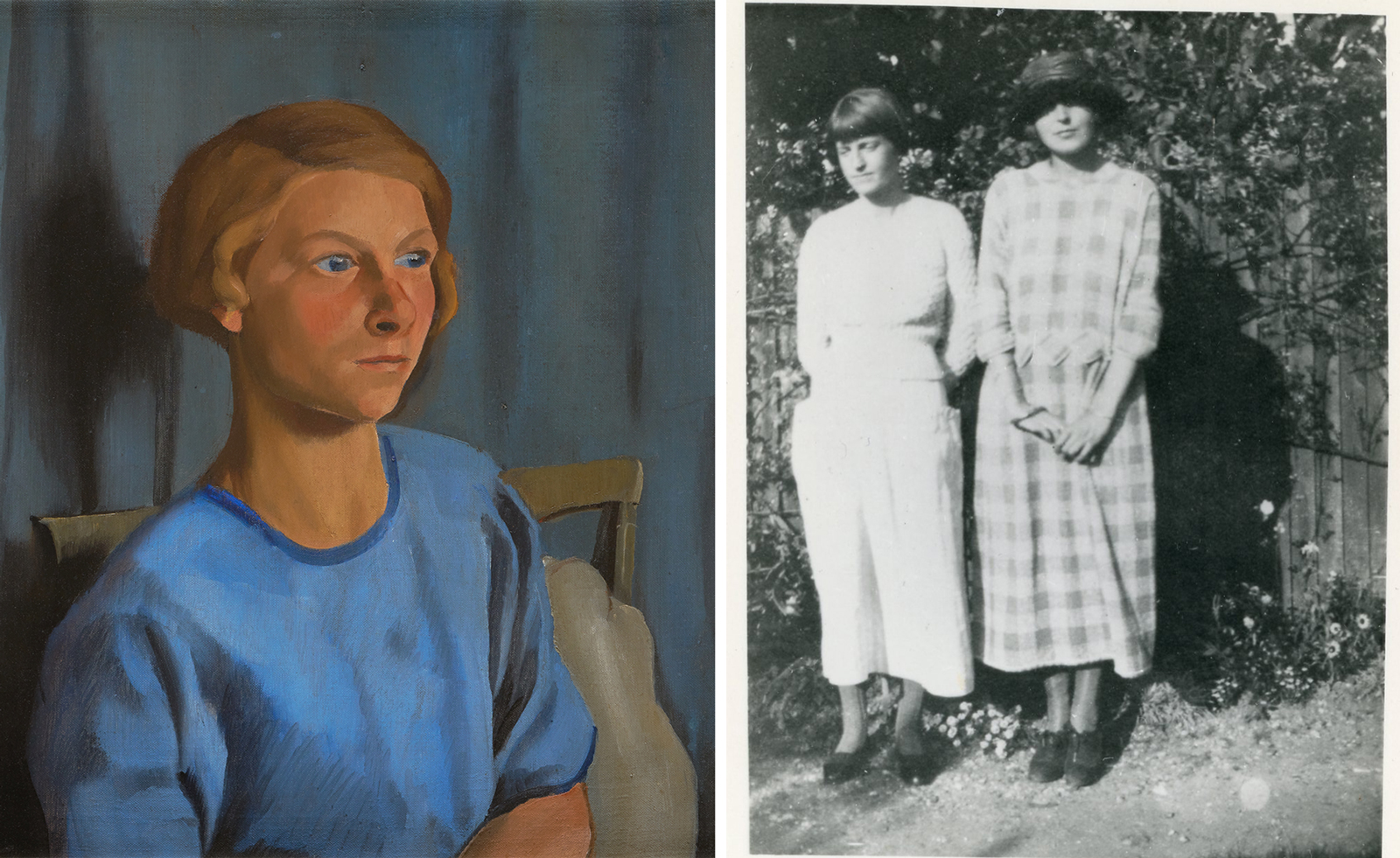

After meeting at London’s Slade School of Art in 1918 the two women – both of them artists, one magnetic and flamboyant, the other shy but a prolific artist – would go on to forge a radical queer and creative partnership that would span a rich body of work over several decades: still lifes, drawings, and portraits. As far as the public was concerned these were Preece’s works; Hepworth, however, was secretly the artist.

This was a deception that would fool the art world – including Bloomsbury Group alumni Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant (Preece was well known in Bloomsbury circles) – until 1996. Now, the new exhibition charts Hepworth and Preece’s creative legacy not only through their work but also through a rich body of archival material – and, for the first time, correctly attributes Hepworth’s own work to her.

How Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece fooled the art world

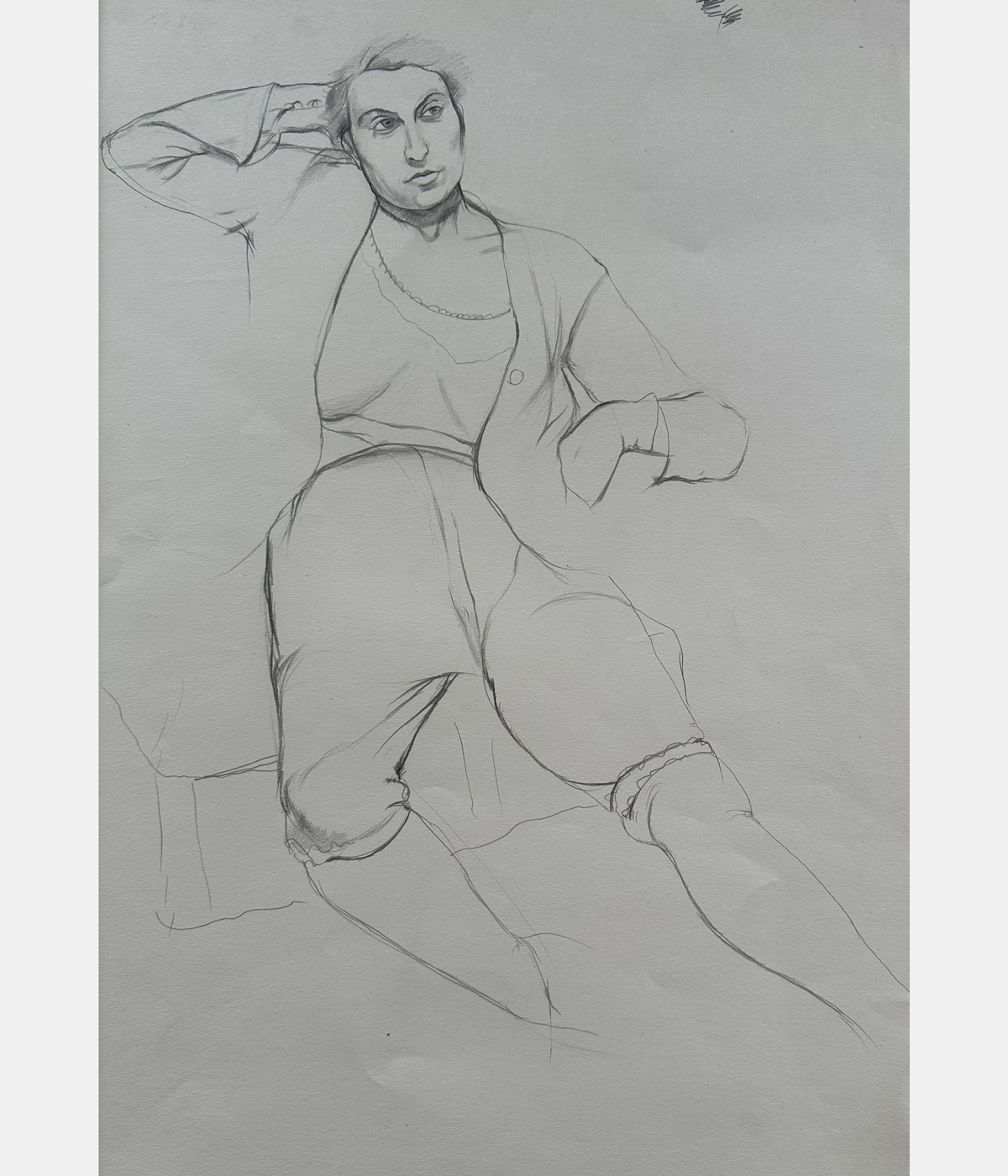

After Slade, the women moved to Paris to study at the Académie Colarossi, painting alongside luminaries such as Henry Moore and Cedric Morris. Here, Hepworth would spend the next few years refining her style, incorporating sharp lines, sinuous forms, bold brushstrokes and vibrant colours into her works, just like her Post-Impressionist contemporaries. Her still lifes, in particular, show traces of André Lhote's early cubist influence, but this was a style Hepworth would later abandon in pursuit of her own. Bold colour is sparse in her work after this point, save for the rare splashes of verdant green and lurid blues. Instead, most of Hepworth’s paintings are grounded by an earthier, more subdued palette, perhaps mirroring the artist’s reticence to fully unleash her potential.

Although Hepworth’s body of work spanned a wide array of subjects, it was always the female form to which she returned. Preece was her ultimate muse and the subject of countless portraits and nudes, each image radiating a soft sensuality. When the women moved to Cookham, Berkshire, in 1927, Preece would also serve as inspiration to painter Stanley Spencer, whom she would later marry.

Through Spencer’s art, letters and photographs, the show makes no secret of the artist, his wife and her lover’s love triangle (more a square, if we are to consider that Spencer was still married to his first wife, Hilda Carline, when he first met Preece). His unrelenting obsession with Preece is evident in the exhibition’s display of Spencer’s portraits of her; Patricia at Cockmarsh Hill (1935) stands out as perhaps the most telling, as the artist superimposed a wedding ring on her finger, two years before they actually married. Preece continued living with Hepworth throughout her marriage, and the two were even buried in the same grave, with a headstone reading: ‘United in life and in death’.

Although the precise motive behind their hoax – Preece’s marriage, the missigned portraits – isn’t entirely clear, curator Emily Hill suggests that it allowed them to create something meaningful together. Just as Hepworth’s love of Preece shines through in each and every portrait, so does the gravity of her loss after Preece’s passing in 1966. Hepworth's last self-portrait, rendered in sombre, subdued hues, vividly captures her grief, as she continued to paint. Twelve years after her lover’s death, Hepworth would still sign the work as Preece.

‘Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece: An Untold Story’ is on view from 27 March – 8 September 2024 at Charleston in Lewes, UK