A new government fund aims to push wood as a lower carbon substitute for concrete in building and for fossil fuels

Forestry Minister Peeni Henare has announced a $57 million fund to promote investment in domestic wood-processing facilities, as the Government seeks to push wood as a carbon-friendly alternative in construction, fuels, packaging, and even biochemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Starting in July, the Wood Processing Growth Fund will provide about $3 million a year for research, business cases, pilot studies and market development around onshore wood processing projects, Henare told the annual conference of the wood processing and manufacturing sector in Rotorua.

The rest of the money – the majority – is available for companies wanting to build plants or invest in equipment and technology.

“Countries around the world are seeking to reduce emissions, and our comparative advantage of turning sunlight into wood products that are low carbon by their very nature is almost unsurpassed,” Henare said.

READ MORE:

* Climate Commission report: What you need to know * Forestry industry shows its cards at slash enquiry * Zombie forests, carbon sinks and the ETS

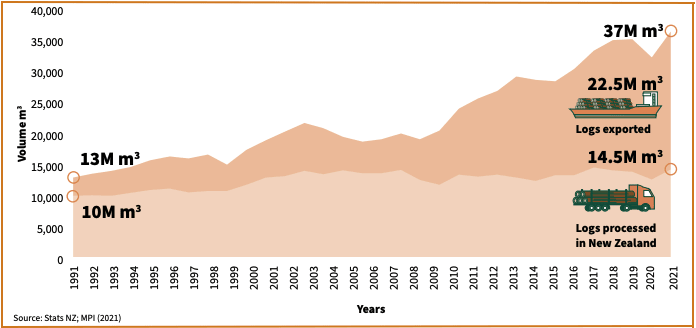

However, last year only about 40 percent of New Zealand’s forest harvest was processed at home; the rest was sent overseas, mostly as low value logs.

“If we can find high value uses for the 60 percent we currently export we will grow our prosperity and help our country transition to a low-carbon future,” Henare said.

The $57m fund is part of $384m committed to forestry and wood processing in Budget 2022 as part of the Government’s emissions reduction strategy.

In November, Te Uru Rākau – NZ Forest Service published its Forestry and Wood Processing Industry Transformation Plan, aimed at getting greater value from the country’s forests.

Since 2020, the volume of wood harvested in New Zealand has doubled to 37 million cubic metres a year, but the processing capacity has remained more or less unchanged at 13-14 million cubic metres, the transformation plan report said (see graphic below).

New technologies are not only changing what we can produce from wood fibre, but are also making processing low value logs more cost-effective in New Zealand, the report said.

A study commissioned by Te Uru Rākau found replacing half of our concrete and steel construction materials with timber could reduce the embodied CO2 emissions in our buildings by 500,000 tonnes. But that would mean increasing wood-processing capability by about 10 percent, to turn an additional 1.3 million cubic metres of logs into high-value engineered wood.

A report from the BioComposites Centre at Bangor University in the UK found that “using timber frames rather than masonry can reduce carbon embodied emissions by around 20 percent per building. When cross-laminated timber is chosen in place of concrete structures the effect is even greater, with carbon embodied emissions reduced by around 60 percent.”

It’s not just primary wood production. Increasing the amount of domestic wood processing would also produce more wood residues, which can be used to make wood pellets to replace coal in industrial processes, and for biofuels, the NZ industry transformation plan report says.

“Over time it will be commercially viable to use wood and wood-based products to replace almost all products and fuels traditionally made from petrochemicals,” Minister Henare said this week.

Wood processing is not just a hot investment area for the Government. In December, Fletcher Building confirmed it was going ahead with building a $275m wood panels plant in Taupo due to be up and running in 2026. It also announced it would spend $97m buying Waipapa, a sawmill, timber treatment and renewable wood fuels group.

But there are risks in the strategy, according to Te Uru Rākau. Log harvests are forecast to decline by 15 percent by 2035, putting pressure on supplies for any new processing plants.

The transformation plan called for the Government to take a leading role in the industry's future, including making sure there was a wider variety of tree species planted, and providing greater clarity in terms of future regulation around forestry and climate change to reduce the risks for private sector investors. It also suggested the Government used its own procurement levers to create demand for wood being used instead of more carbon-intensive alternatives.

Meanwhile, Marty Verry, chief executive of sawmill and timber group Red Stag, called on the Government to recognise the role of wood processors not just forestry companies, in terms of mitigating climate change, by allowing them to participate in the Emissions Trading Scheme.

“Despite many wood processors investing heavily in the expectation that eventually they will be treated consistently and earn New Zealand Units [a measure of greenhouse gases emitted or saved], the Government has to-date pocketed all the accounting value of harvested wood products,” Verry said in an article in Stuff last year.