Fish are constantly surrounded by water, but do they get thirsty? And how would they even drink?

To answer these question, it's crucial to understand how water — a solvent — interacts with other substances like salt, which is a solute, across a cell membrane. Through a process called osmosis, water flows across a membrane from areas with low concentrations of solutes to areas with high concentrations of solutes until the cell can reach some sort of equilibrium with its external environment.

How much water a fish consumes really depends on how much salt is in its surrounding habitat. While fish do drink some water — salty or fresh, depending on their surroundings — through their mouths, they mostly absorb it through their skin and gills via osmosis.

"You've got to think of a fish as sort of a leaky boat in the water," Tim Grabowski, a marine biologist at the University of Hawaii, told Live Science. "You constantly have a movement of either water or the salts that are in the water between the fish's body and the external environment."

Related: Why do animals keep evolving into crabs?

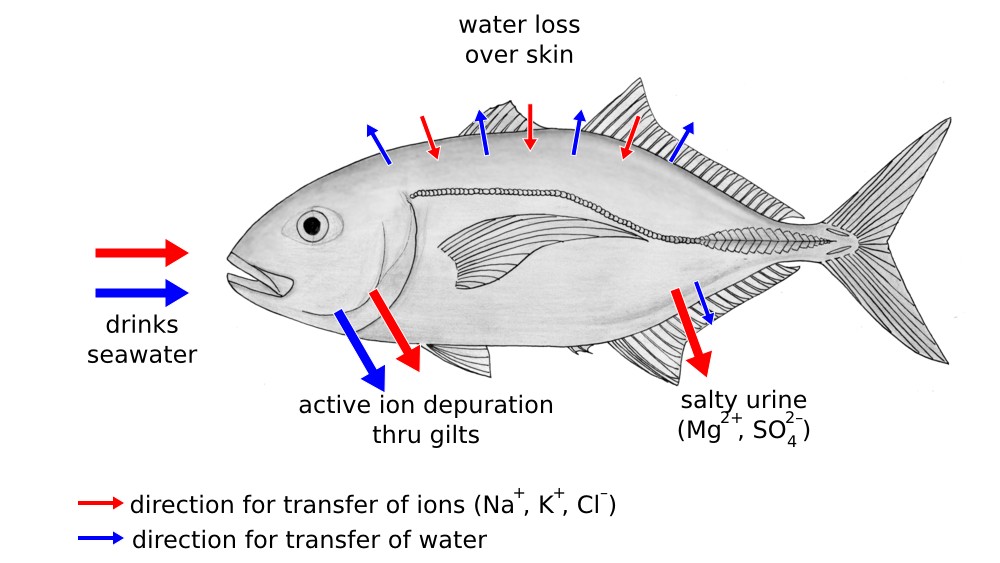

Let's start with how fish in the ocean stay hydrated. Seawater has roughly 4.7 ounces of dissolved salt per gallon (35 grams per liter), while most fish blood has roughly 1.2 ounces of salt per gallon (9 grams per liter). This imbalance is "going to constantly cause the fish to lose water to the external environment and to be sort of invaded by salt into its cells and inside of its body," Grabowski said. "A saltwater fish is always thirsty. It's drinking all the time."

These fish need a way to retain the water they are drinking from the ocean but get rid of the salt. To do this, fish have specialized cells in their gills called chloride cells, which essentially act as tiny pumps that actively push salt out of their bodies. To maintain as much water as they can, marine fish rarely pee, and when they do, their urine is exceptionally salty.

Freshwater fish face the exact opposite challenge as marine fish when it comes to water, according to Melanie Stiassny, a curator in the Ichthyology Department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

"If you're a freshwater fish, you have a problem because water is constantly being pumped into you," Stiassny told Live Science. Too much water can be a bad thing because it can dilute the body's salt content, which is crucial for regulating blood pressure and supporting muscle function. Freshwater fish spend all their time trying to keep water out of their bodies and never drink it — at least on purpose.

"[Freshwater fish] might take in water incidentally when it feeds and stuff like that, but it's never drinking any water," Grabowski said. To combat this constant barrage of liquid, "it's peeing continuously," he added. But no need to fret about swimming in a bunch of fish pee in lakes or rivers; the urine is mostly just water, Grabowski said.

Similar to ocean fish, freshwater fish also have chloride cells, but their pumps work by pulling salt into their bodies rather than out of them. However, operating these pumps can take a lot of effort.

"[Water] is passively coming in, but it has to be energetically removed," Stiassny said. "There is a cost to that, particularly for the saltwater fish which really has to pump out all of that salt that it's brought into its system by having to drink lots of water."

There are some fish that follow an entirely different rulebook for drinking water. For example, sharks maintain high concentrations of urea — a salty byproduct of ammonia — in their body. "[Sharks] stop that passive incoming of water because they've balanced it with the urea and their blood — so they're basically as salty as saltwater," Stiassny said. When they do take in seawater, sharks expel the excess salt through chloride cells at a gland in their rectum.

No matter what the mechanism, though, the key to staying hydrated for all fish is finding the perfect salty balance.