In the late 1740s, Samuel Meadwell arrived in London. A “raw country fellow” from Northamptonshire, he had come to work as a distiller’s apprentice and hoped to make his fortune.

When a pair of women told him there was “something very particular in [his] face”, he was intrigued. They introduced him to a widow called Mary Smith, who allegedly practised “the art of astrology, before very great people, princes, and the like”. She persuaded Meadwell to wrap all his money in a handkerchief with two peppercorns, some salt and a little mould. After waiting three hours, she explained, he would discover a great fortune.

Meadwell discovered only that his money had been replaced with scraps of metal. Smith was deported for fraud, while Meadwell learned a lesson about city life. He bemoaned his naivety – but he was not alone in believing in the power of astrologers, or the potential for magical methods to reveal weighty secrets.

In early modern Britain (1500-1750), divination was widespread. People consulted diviners to find stolen goods, learn about the next harvest, or scrutinise their marriage fortunes. Sometimes they wanted to know what diseases or disasters loomed, and several nobles exhibited an unwholesome interest in the monarch’s date of demise.

The sex of unborn children was another topic of speculation: when Anne Boleyn gave birth to the future Elizabeth I in 1533, she disappointed not only Henry VIII, but also a whole host of “astrologers, sorcerers, and sorceresses” who had assured the couple that a male heir was forthcoming.

Diviners came from across the social spectrum. Learned astrologers could command audiences with kings and queens. Most people, however, relied on the services of a local cunning-man or woman.

There were also so-called “Egyptian” fortunetellers who roamed the country reading palms. These travellers probably did not have African origins. A hostile 1673 work claimed that they were “great pretenders” who sought to dupe “the ignorant” by associating themselves with Egyptians, “a people heretofore very famous for astronomy, natural magic, [and] the art of divination”.

The authorities did not approve. In 1530, an act passed by Henry VIII’s parliament sought to expel “Egyptians” from the country, complaining that they conned people using “great, subtle, and crafty means” such as fortunetelling.

Underpinning many divinatory methods was the belief that God’s divine plan was encoded in the patterns of the natural world. Palmistry relied on interpreting the marks God had traced on the body. Astrologers, meanwhile, focused on the movements of the planets.

Between 1658 and 1664, a woman called Sarah Jinner published almanacks containing astrological readings for the forthcoming year. She ranged from predicting “desperate and unreconciliable wars” to cautioning women that: “We find Mercury in Pisces retrograde in the 6th House, [which] denoteth that servants will generally be cross, vexatious, and intolerable, especially maidservants.”

The behaviour of animals was also considered portentous. A pamphlet from circa 1690 declared that “to meet a swine the first thing in a morning, carrying straw in its mouth, denotes a maid, or widow, shall soon be married, and very fruitful in children”. On the other hand, magpies flying around you signified “much strife and brawling in marriage”.

When a great murmuration of starlings was spied battling in the air above Cork in 1621, people whispered that it signified divine anger. Eight months later the city was devastated by a fire.

Other divination practices relied on chance. Cheap pamphlets outlined ways of divining with dice, the idea being that God determined the outcome. Another practice was to open a Bible randomly and consult the first passage that caught the eye. Bibles could alternatively be used to catch thieves. The usual method was to insert a key into the Bible, recite the names of the suspects, and wait for the Bible or the key to move.

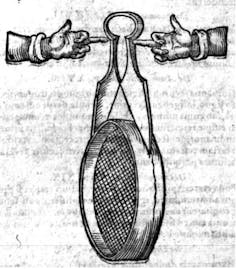

A similar technique involved suspending a sieve from a pair of shears. The sieve would rotate when a thief’s name was mentioned.

Divination and the authorities

These practices were viewed with suspicion by the ecclesiastical and secular authorities, especially after the 16th-century Reformation.

A Welsh scholar warned in 1711 that using the Bible as an “instrument of prognostication” was “the greatest insult that anyone can give to the scriptures”. Church courts punished people for the “devilry” of divining with a sieve and shears.

Most dangerous of all was divination by consulting spirits. The Scottish cunning-man Andrew Man claimed to have an angelic adviser, Christsonday, who told him whether upcoming years would be good or bad. He was also in a sexual relationship with the Fairy Queen, who had promised to teach him to “know all things”. Leading local figures concluded that Man had really been cavorting with devils. He was tried for witchcraft, and executed in 1598.

In general, however, cunning-folk enjoyed good standing within their communities. Currents of scepticism flowed faster during the 18th-century Enlightenment. A 1762 work expressed a common view when it blamed belief in divination on the “ignorance and darkness” that “covered the minds of mankind”. But divinatory practices were themselves a quest for enlightenment, and the prospect of unravelling the mysteries of the future has remained compelling up to the present day.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Martha McGill receives funding from the British Academy.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.