Most men carry one X and one Y sex chromosome in each of their body's cells. However, over their lifetimes, many men start losing Y chromosomes in a portion of their cells, and this might hamper their ability to fight certain cancers, a new mouse study suggests.

Loss of the Y chromosome in a percentage of men's cells may help cancer — specifically bladder cancer — sneak past the body's immune system and proliferate more rapidly, according to the study, published June 21 in the journal Nature.

"It's the first demonstration that losing Y chromosome makes the cancer more aggressive," study lead author Dr. Dan Theodorescu, a physician and director of the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, told Live Science.

But there may be a silver lining to these results: The same mechanisms that make bladder cancer cells in men with Y chromosome loss more aggressive may also make them more vulnerable to cancer treatments called immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Related: Is the Y chromosome dying out?

Y chromosome loss has previously been associated with an increased risk of certain illnesses, including heart disease and Alzheimer's disease. The phenomenon can be observed in various types of cells, including blood cells, and it's also seen in different types of cancer cells. This includes an estimated 10% to 40% of bladder cancers, the study authors wrote, which are much more common in men than women.

To determine the impact of this phenomenon in bladder cancer, researchers compared the growth rates of bladder cancer cells in one set of laboratory mice injected with Y-negative cells and another injected with Y-positive cells. The growth in tumor cells that lacked Y chromosomes was aggressive — twice that of tumors with intact chromosomes.

To figure out why, the team injected Y-negative and Y-positive cells into immunocompromised mice. Unlike the previous experiment, each tumor grew at roughly the same rate, suggesting that Y chromosome loss affected the immune system somehow.

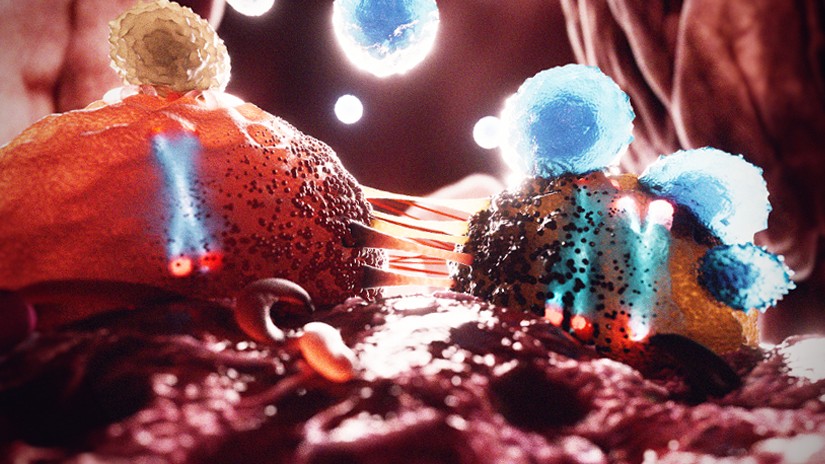

The researchers repeated this experiment in genetically altered mice that lacked different types of immune cells. T-cells, which normally play a massive role in fighting off cancer cells in the body, were most affected by Y chromosome loss.

According to the study, the Y-negative cells are likely driving something called T-cell exhaustion, which is when these immune cells lose their ability to kill certain cells, like cancerous cells or those infected by viruses. As a result, cancer cells can easily evade the body's immune system, and tumors can grow much more aggressively than if the person had fully functional T-cells.

In these cases, doctors can potentially help boost a patient's immune system with immune checkpoint inhibitors, which revive T-cells enough to start attacking cancer cells. When the researchers treated the mice with these drugs, the animals with Y-negative tumors responded better than those with Y-positive tumors.

To check if this affects human cancer treatment, the scientists reviewed data from two groups of men with bladder cancer in whom they were able to indirectly measure Y chromosome loss in tumor cells. One group consisted of patients who had their bladders removed, and the other group was made up of patients who were instead treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Patients with Y loss in their tumors were less likely to survive in the first group than those with cells that had intact Y. However, when treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, those with Y loss had an overall better prognosis than those with intact Y.

"I think this is elegant work," Dr. Jeanny Aragon-Ching, an oncologist who specializes in bladder cancers, told Live Science in an email. The research "showed that the loss of Y chromosome may in part be an explanation of why there is increased preponderance of bladder cancer [once] a man ages," said Aragon-Ching, who was not involved in the study.

However, not all cancers are likely to react to the loss of the Y chromosome in the same way, so there's some controversy as to whether Y loss would always be bad for a patient's prognosis, she added. For example, in another recent study in Nature, researchers studying colorectal cancer in mice found that Y chromosome loss may actually make the tumors less aggressive.

No matter the cancer, however, Theodorescu said that it will be a critical next step to develop a clinical test that can determine if a patient has Y chromosome loss in their tumors, so that physicians can tailor treatment accordingly.