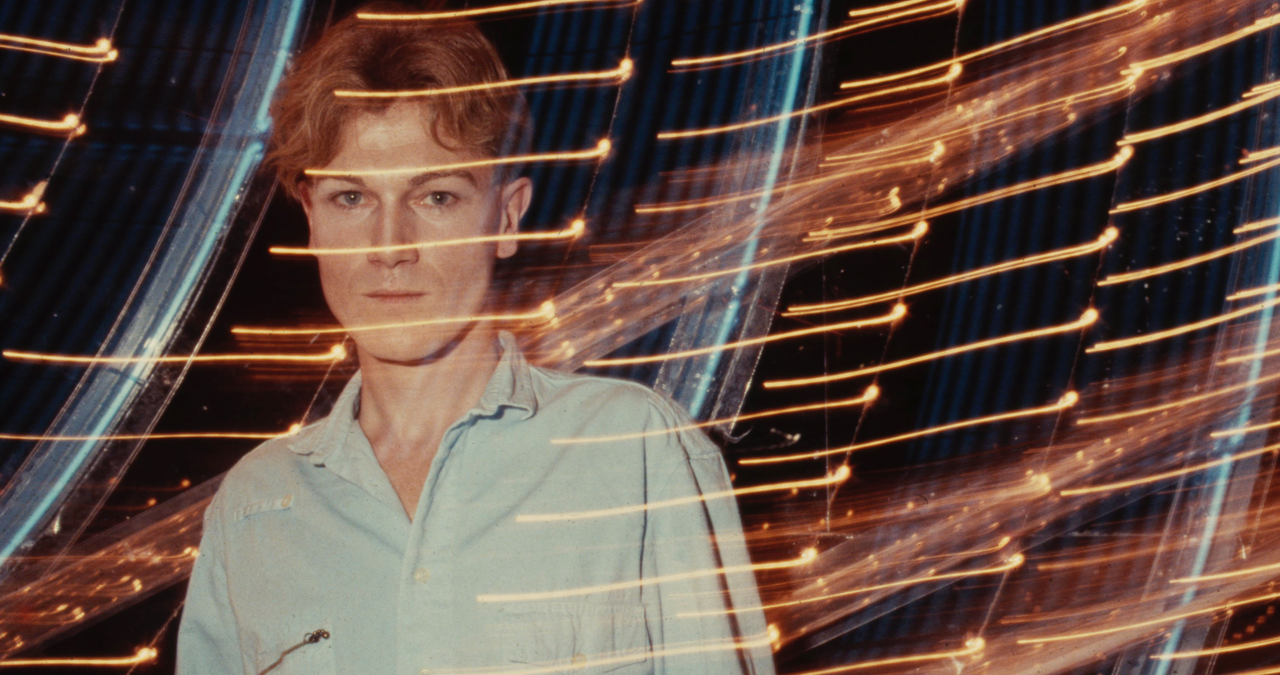

The word ‘innovator’ is often overused in electronic music with few having the credentials to live up to the accolade. John Foxx is an exception. Born Dennis Leigh in Chorley, Lancashire, the former leader of synthpop band Ultravox was years ahead of his time.

While their debut album was primarily post-punk, Foxx envisioned the future on its closing electronic ballad My Sex and had to depart the group to fully realise it. The result was his seminal solo album Metamatic, released three years later using little more than a Roland CR-78 drum machine, Arp Odyssey and an Elka String Machine.

Despite luminous follow-up albums such as The Garden and The Golden Section, Foxx was trampled on by the new wave explosion and shifted his focus to photography and graphic design.

Upon his return in 1997, he had completely reinvented himself with the release of the ambient masterpiece, Cathedral Oceans. In recent decades, Foxx has teamed up on numerous projects with Louis Gordon, analogue enthusiast Benge (The Maths), and piano master Harold Budd, whose eternal influence remains visible on Foxx’s 2023 LP, The Arcades Project.

MR: What inspired you to instigate the synthpop movement through the adoption of synthesisers and drum machines as early as 1976?

John Foxx: “They did something that other machines couldn’t do - you tried them out and if they didn’t have too many multifunction menus or badly designed interfaces they got adopted. For me, it’s always been about simplicity of use - if it works right away and sounds good, I’ll have it; otherwise it gets thrown aside.

“At that point, I felt guitars and drums had run their course. Rock had become a cliché and we also had to deal with punk, which was a great rethinking of rock music but got very lazy and tedious. The way to rebel against that was to adopt synthesisers in a punk manner.

To get the full range we put brutal drum machines and sounds through guitar and bass amps, and I wanted to see how far I could go with this new instrument. As Phil Oakley and Daniel Miller said, it was a one-finger revolution.”

MR: Despite the fact you were using synths well before Gary Numan discovered them, was there an element of wanting to ride the wave of his success?

JF: “We invented the wave because electronics didn’t really exist in rock and roll before we came along. Roxy Music had done a bit of it with Brian Eno, and Virginia Plain was a great record that inspired me. I was also interested in Neu!’s first few records and British psychedelia like The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows.

“The track When You Walk Through Me from Systems of Romance was an updated version of that way before Oasis and the Manchester movement. I don’t know if any of them ever listened to us, but when we got that right all the other bands fell into it. We invented a language that U2 and Simple Minds carried out and, with a few exceptions, the critics hated it, but it then became the template as guitar, synths and electronic effects were being explored by everyone.”

MR: Your version of electronic rock actually went one step further than Gary Numan’s because Metamatic was 100% electronic…

JF: "Metamatic was a clear-out based on my desire to rethink popular music completely. I started that idea in 1976 with My Sex, but because Ultravox was a band I couldn’t pursue it alone and we didn’t have the instruments to do it. With each album I always made sure there was at least one song like that at the end of the record, which was the lead up to Metamatic.

“You make a different kind of music with synthesisers because you have to completely rewrite all the instruments, and when you work with a drum machine all the functions have to be re-examined because a drummer doesn’t function in that environment.”

MR: If you listen to Depeche Mode around 1981 they sound very twee and dated, whereas Metamatic still stands up well today. Was that futuristic aesthetic entirely instinctual?

JF: “I wasn’t thinking about the future, I just felt like I had to get the idea done and it often takes the rest of the world some time to catch up. I don’t mean that in a vain sort of way. You’ve got the gear and off you go, but most people are still embedded in the things they really love so your ideas don’t start to come through until ten years later.

"You imagine everyone will like it right away and it surprises you when no one does [laughs]. It’s an awful feeling when that happens.”

MR: 1981’s The Garden probably had more in common with your final Ultravox album than Metamatic. Why did you bookend electro-pop at that point?

JF: “There were several reasons. Metamatic was the first synth record of the 1980s, but because of Gary Numan’s success every label wanted a synthesiser record. I’d spent five or six years trying to develop my own territory and thought I’d be alone in doing that, but suddenly everybody and his dog had a synth band, so what the hell do I do now?

“I had the song Systems of Romance and a lot of other half-finished stuff from that era, so I put them all together and that became The Garden. Metamatic was all about ‘70s Britain, which was a bit grey and concrete, but I’d gone off to Italy and seen the sunshine, which changed things completely.”

MR: For 1983’s The Golden Section you enlisted Art of Noise’s J. J. Jeczalik and his Fairlight CMI…

JF: “It was a small world really and we were all in and out of each other’s studios. Trevor Horn’s Video Killed the Radio Star took him around two years to make and I used to meet him all the time. He’d enlisted people like J.J. and I’d bump into him whenever I used Trevor’s studio.

When I heard J.J.’s version of a cello using the Fairlight I thought it sounded great, so I got him to do that on the track Endlessly. He was kind enough to lend it to me, but I always felt slightly uneasy with digital stuff.

“I like the artificiality of synthesisers, but digital always felt too imitative of real instruments. It was too posh and I wanted something rougher. Digital is obedient, which is useful in certain circumstances, but analogue misbehaves and that wildness is appealing. They’re very different technologies with different natures, so it’s good to use them in conjunction.”

MR: Of all the synths you used, the Arp Odyssey is the one that appears across almost all of your early albums. What was so special about it?

JF: “The Odyssey has a viciousness that really fits what I wanted to make, but it can also make very delicate and beautiful sounds. It’s one of those real rogue machines and it’s a bit unpredictable - the amount of amplifiers I’ve damaged and tweeters I’ve blown is incredible. I never analyse what I’m doing on it; I just play with it until I get something interesting and you can mould the sound in a way that’s not so easy with other synthesisers.”

MR: Some people like to understand what’s under the hood of a machine. Have you deliberately tried to avoid that?

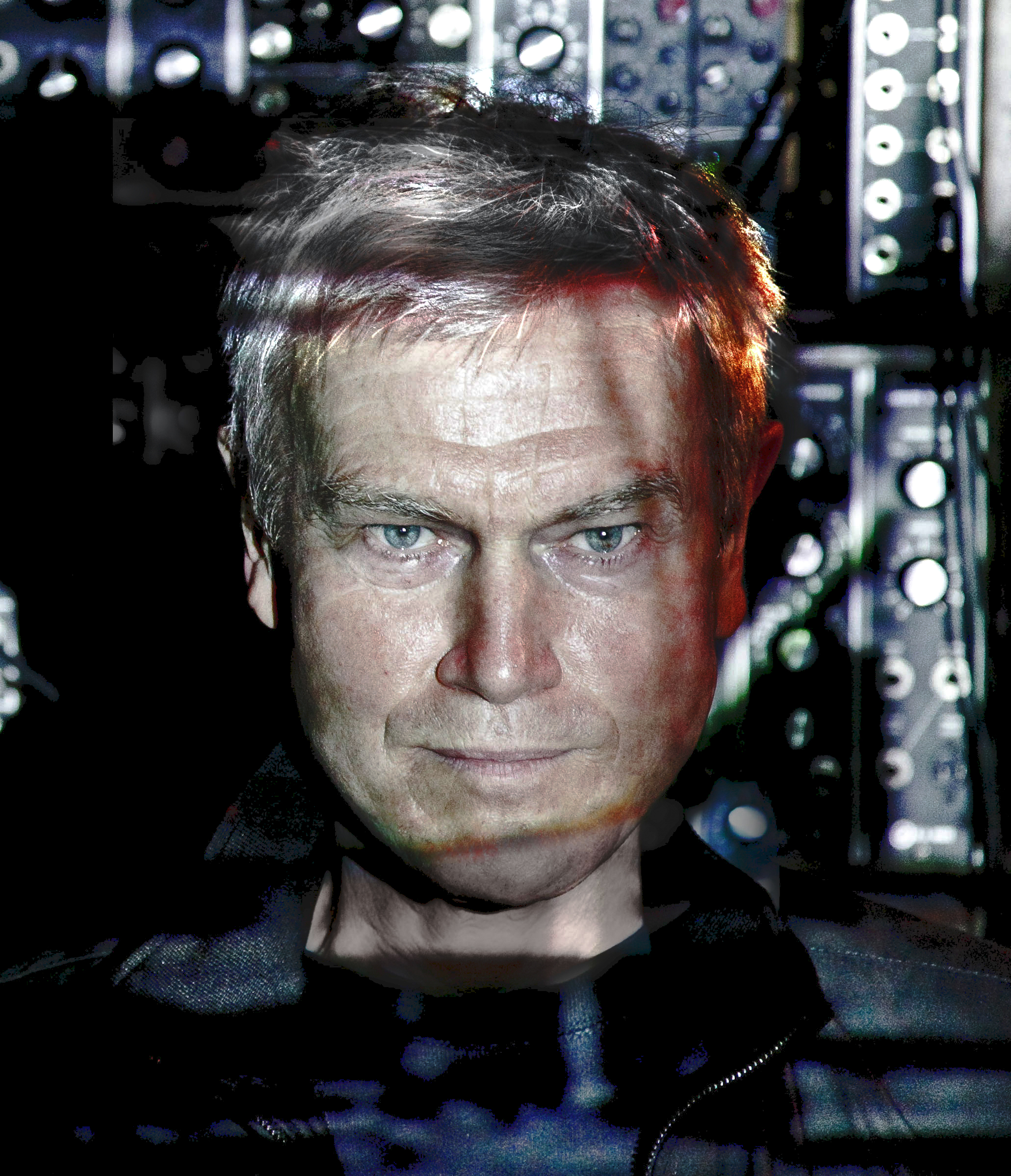

JF: “It’s not how my mind works, but I’m grateful for people who do know about those things. For instance, I like working with Benge because he likes the radical and unpredictable but can instantly synchronise various synthesisers with ancient drum machines.

"Benge and Connie Plank are like twins really. They’re great lovers of technology, technique and the systems beneath them that allow that madness to take place. Working with someone like that is a pleasure, but the reason I’m so impatient is because if you have a song or idea in the making you can lose it very quickly by fiddling with equipment.”

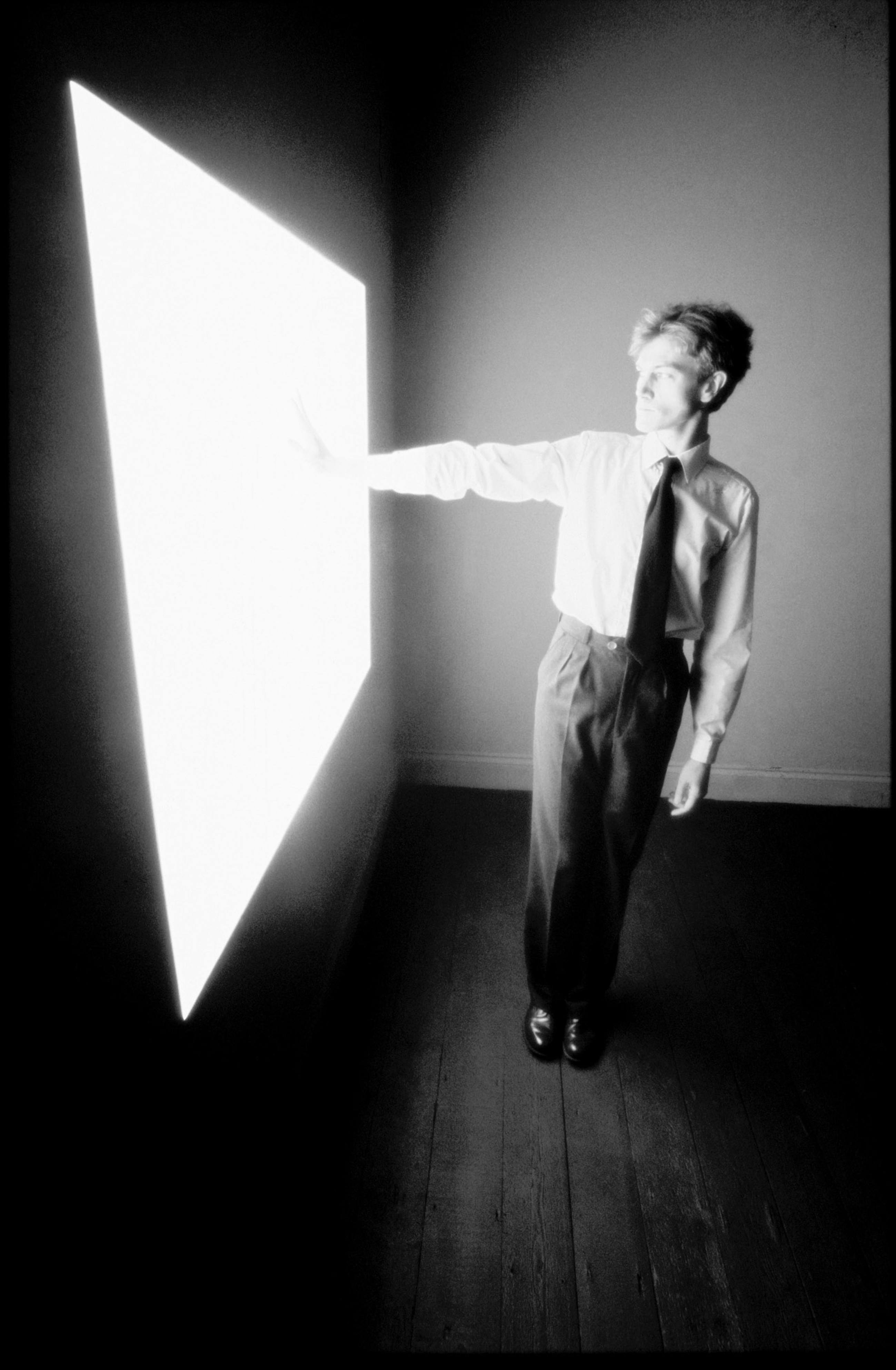

MR: In 1997, you suddenly re-appeared with the ambient album Cathedral Oceans. Presumably your primary interest here was to use effects as an instrument?

JF: “I’ve always been interested in how echo and reverberation worked and how musical it is, but it was only when I got hold of digital effects that I realised how reverb and reverberation are not just effects but musical instruments. Even echo can change a piece of music completely - not just the feel, but how the harmonics operate.

“When I was in a choir, I realised that there was a delay in the church and by the time my voice came back to me I was harmonising with the multiple reflections as they came off the walls. Digital reverbs made it possible to have a cathedral in a little box that I could experiment with - the first Alesis reverbs were wonderful and I still use them today.”

MR: That realisation must have totally redefined how you thought about and made music?

JF: “I started working with 30-second delays and what I found is that, oddly enough, when you make music like that your heartbeat synchronises with it. You slow down without realising and it’s not just psychological because you move instinctively with the rhythm just as you do when you dance to 120 BPM at a club. It’s like being in the womb, where you have to synchronise your heartbeat with the big mother. With Cathedral Oceans, it’s a tide. It’s much slower and swaying, so we synchronise with the big ocean.

MR: Do you feel there’s been any game-changing hardware technologies post-2000?

JF: “Eurorack was like going back to organic gardening; everything got a bit artificial and you realised you’d missed something along the way. Guys from Detroit were getting hold of cheap, abandoned machines from pawn shops and revisiting them, and manufacturers and enthusiasts realised there was a market for this stuff so why not make it again?

"Alongside that, what you have in a laptop now is probably more accurate than what you had in recording studios in the ‘70s or ‘80s and there’s a joy in discovering that mix of digital control and wild analogue beauty."

“You can imitate analogue, but you can’t make it any other way. It’s a bit like Formica. When we first got it we tried to make it look like wood, which quickly became kitsch, silly and rather ugly. The same thing happened when analogue and digital tried to imitate orchestras, but it’s just bad thinking. It’s only when you discard that and ask what does this actually sound like when it’s unleashed that you can see the beauty of it.”

MR: Last year’s The Arcades Project is a piano-based album. Why return to the simplicity of using one instrument?

JF:“I’ve always loved single instrument recordings because they’re incredibly beautiful. For example, there’s a musician called David Darling who made a seminal single-instrument record by recording a cello with a delay. I also love Erik Satie, whose philosophy was to make furniture music for living rooms.

“My aunt had given me a piano when I was 12, but I was never taught. I discovered the instrument’s magical properties because it has more harmonics available than even a sitar. If you let the notes ring, they have a movement all of their own, even without reverb, but when you put that into a reverb it multiplies the whole thing until it sounds like an orchestral background.”

MR: Is there one thing you learned from working with Harold Budd that you could convey to those interested in making ambient music?

JF: “Working with Harold was inspirational and the simplest and best recording experience I’ve ever had because he knew exactly what he wanted but was not dictatorial about it. He didn’t have hard and fast rules, except to say that things should be simple and fluid, and don’t be afraid to abandon anything because there will always be more ideas.

“Once you start recording you have to feel that you’re in this luminous, magical place where you can follow your own instincts. When you set those conditions and it feels right, you’re capable of doing anything, but you have to get the right sound before you’re free to take off. I don’t count myself as a musician - I make sounds and intuitively follow them, but once I get the right sound I can play anything, and if I don’t I can’t play anything. That’s the first lesson I learnt.”

MR: Technology-wise, the latest advancement, or threat depending on your viewpoint, is artificial intelligence. Do you have an opinion on that topic?

JF: “I was in a studio recently and we took apart the track Underpass from the stereo mix, removing the drums, synths and vocals using artificial intelligence. It was quick and crude but very impressive. I believe The Beatle’s Revolver was dissected and rebuilt using that technique and I think that’s marvellous. You can reconstruct things but also deconstruct the reconstruction and make something new from it. The results are not always satisfactory, but you can see how it could be refined until you can imitate anything.

“But again, this is the Formica period isn’t it? We’re imitating previous forms. The interesting thing would be to set AI free by programming it to make new forms of music. We shouldn’t be afraid to use it because I heard the same things said about synthesisers when they came out. The Musician’s Union and the BBC thought we were putting musicians out of work, but we were actually creating more opportunities because people would never have made music without those instruments. AI could easily be the same thing.”

MR: Can you envisage a way in which AI disrupts the actual music-listening experience?

JF: “There’s a Samuel R. Delaney novel called Nova that I read when I was hitchhiking in Spain in the 1960s. In that novel, there’s a character called The Mouse who has a thing called a syrinx which is an imaginary instrument based on a sitar. When played it throws out a neural pattern that affects everyone in the room so they’re subject to this hallucination of music and visuals. That’s a wonderful concept for a future version of music and immersive visuals.

“Through AI, we’ll be able to construct marvellous machinery like this and I think that should be the aim. You won’t be creative if you’re afraid. Rather than disseminating or dissecting old forms, let’s think what we can make that hasn’t been explored. For instance, sometimes I’d like to sing like an opera singer. I can’t do that now, but I could ask AI to pitch my voice to sound like Pavarotti and it would be wonderful to sing like that live, using the instrument.”

MR: Is there a bucket list of musical projects that you’re still yearning to complete?

JF: “At the moment I’m in the middle of making a Maths album with Benge, Rob Simon and Hannah Peel, there’s a piano album that’s about to come out and one that I’m constantly working on. I’m really fascinated by piano – I get up and play every day and it’s very heartening because in my old age I still feel I’m getting a bit better.

“You’re supposed to get worse at things, but that hasn’t kicked in yet and it never did with Harold. His judgment and understanding got finer, more beautiful and more intuitive. He’s my version of AI - I want to react to Harold forever.”

John Foxx’s Metamatic will be re-released on limited addition grey vinyl on Jan 17, 2025. Meanwhile, his latest book of visual art, Electricity and Ghosts, can be ordered here.