BOSTON—Baseball’s most prized commodity is about to hit free agency.

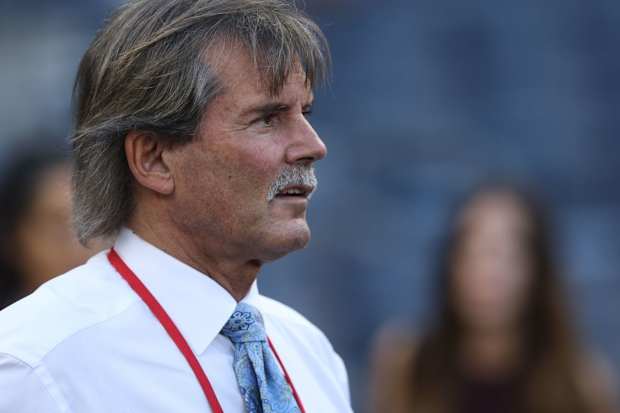

Dennis Eckersley is retiring from the game of baseball. Again. This farewell, Eck claims, will be a permanent one.

Unless, perhaps, the baseball gods interfere.

Eckersley has been broadcasting, both nationally and locally, for the past 20 years. The vast majority of that time has been spent providing color commentary for the Boston Red Sox, delivering an approach that is as honest as it is compelling.

A walking, talking baseball historian, Eck brings the past to life when he calls games. He is never afraid to state what needs to be said. Animated, lively, and overflowing with passion, it seems preposterous to imagine Eckersley willingly exiting a game that has fit him like a hand in a glove. Yet, after more than 50 years of being affiliated in and around the majors, he believes the time is right to start the next chapter of his life.

“I’m really not sure what I’ll do next,” Eckersley says. “It’s my call. I’m proud of what I’ve done as a broadcaster.”

Stan Szeto/USA TODAY Sports

Eckersley’s first retirement came in 1998, followed by an induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2004 that punctuated a legendary career. He finished his last season as a reliever for the Red Sox, where he also pitched as a starter in the late 70s and early 80s. Now, he steps away from the broadcasting booth, a job he has performed in exquisite fashion.

Similar to his pitching career, where he experienced a series of highs and lows as a starter before redefining the game as a reliever, Eck has become one of baseball’s most compelling voices. He brought an old-fashioned charisma to his calls, as well as the same tenacity that once made him so dominant on the mound.

“All I wanted people to know was that I was all there,” Eckersley says. “It was no different from when I was a player. You were getting me, the whole guy–the good and the bad.”

Loyal listeners will immediately notice a gaping hole next season without Eckersley on the broadcast. He is the rare type of analyst, one willing to criticize a player’s on-field performance. That style is not always popular among players. Eckersley experienced issues within the Sox organization within the past decade, which reached its breaking point five years ago when former ace David Price lit into Eck on a team flight for being too critical of players–claiming Eck forgot how hard it is to play the game. Price received very little sympathy for his tirade–Eckersley’s trials and tribulations with the game are well documented, no greater than when he served up the most inspirational (or soul-crushing, depending on your rooting interest) home run of all-time in the 1988 World Series as Kirk Gibson crushed a backdoor slider into Dodger Stadium’s right field pavilion. Forgotten from that evening is Eckersley spending 45 minutes after the game speaking with reporters, facing the music and owning his mistake.

Part of baseball is failure. Eckersley understands that better than most.

“I think players, myself included when I played, are sensitive,” Eckersley says. “But to do this job, you have to be out of the dugout.”

This past summer, Eck criticized the state of the Pittsburgh Pirates, aptly describing the franchise as a “hodgepodge of nothingness.” That particular combination of adjectives isn’t one you hear often. While it bothered some of the Pirates, it is the type of commentary that serves as a breath of fresh air for listeners.

“This isn’t easy,” Eckersley says. “You have to give yourself. It’s a risk to say what you want to say.

“I’ve been through the highest of the highs and the lowest of the lows. Does that give me the right to criticize? I still don’t know.”

Winslow Townson/USA TODAY Sports

Eckersley should be part of a national broadcast. That would be best for baseball, allowing a distinguished alum to provide the lyrics to the game’s soundtrack.

The estimable Dave O’Brien, who is the play-by-play lead for the Sox on NESN, shared the pleasure of calling games with Eckersley. No stranger to national broadcasts with his work on ESPN, O’Brien also wishes Eckersley had done more nationally.

“I do feel the rest of the country has been shortchanged a little bit by not being able to hear Eck broadcast,” O’Brien says. “A lot of the things that made him great on the mound also translated into the booth, and that means the passion and the joy he played with. That’s the way he is in the booth, too.

“I’m not saying I’ve tried to talk him out of retirement, but he should have been scooped up years ago. The honest way he broadcasts the game, fans love it. He speaks from the heart, and he has such a high regard for the game. And he never forgot how tough this game is—anyone who says that has no idea what they’re talking about. Our whole crew looks forward to coming into the booth and spending three hours with Dennis Eckersley. I think every Red Sox fan feels the same way, too.”

Eck’s honesty will be sorely missed. So will, of course, his vernacular. He has embraced his role as the game’s unofficial poet laureate, reciting the beauty of educated cheese (a fastball with precise location), gas (velocity), a punchout (strikeout), salad (finesse pitching), and a slam johnson (a significant grand slam).

Baseball icon Roger Clemens, who was briefly teammates with Eckersley in ’84, continues to be mesmerized by Eck’s command of the baseball lexicon.

“Eck’s language, that’s a topic all to itself,” said Clemens. “Listen to him use the word ‘salad’. That means the other pitcher is throwing brutally. But Eck has different meanings for the same words. When there’s moss on your salad, which means you’re throwing well with some hair.

“All of it shows his mastery of this game. Eck pays such close attention to detail. And he’s so smart. As a power pitcher, he could exploit the corners so well. That’s the same way he is with his insight. Like that pinpoint control, Eck knows exactly how to communicate this game. Eck makes this game even more fun.”

He credits that colorful vernacular to former big leaguer Pat Dobson, who learned it from his peers.

“That’s baseball,” Eckersley says. “I try to bring energy to the game. There are so many moments in this game, and you need to bring the right energy. I remember Mookie Betts hitting a [grand] slam, and I yelled, ‘It’s time to party!’ I’m always ready to party. That’s a pitching thing. When you go after somebody, that means it’s time to go, it’s time to party.

“Everything we do, it’s handed down, generation to generation. I’ve held onto all of it for the past 40 years. But something like cheese? Or it’s time to party? That’s been around a lot longer than me.”

Baseball will continue to beat on without Eckersley, but the game will certainly miss its famed, mullet-haired, mustachioed closer. Eck is the product of a bygone era—he pitched in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, reaching the highest of highs (a three-hit shutout in his first-ever start, a World Series championship, a Cy Young, and a Most Valuable Player award) while also hitting the dregs. Eck was traded on multiple occasions, deemed inconsequential to the future of those respective franchises. Then fate intervened, and he landed in Oakland and played under Tony La Russa.

RVR Photos/USA TODAY Sports

Prior to his run in Oakland, Eck was also an established starter for the Cleveland Indians, Sox, and Chicago Cubs. As implausible as it seemed at the time, a trade to the Athletics forever changed the trajectory of his career.

“I still think back to spring training with the Cubs in ’87,” he reminisced. “I was traded at the end of that spring training. Right before the trade, I’m pitching a game against Oakland, and I’m getting killed—but I needed to get my 80 pitches. At that point, it’s something like 6-0.”

That Athletics club was only a season away from winning three straight pennants and was loaded with emerging superstars that included Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire. But it was the fiery La Russa who would bond most closely with Eckersley.

“Canseco had already homered off me that game, and then he hit a ball off the wall,” continued Eck. “He’s on second base, I’m in the stretch, and he takes off to go to third. Again, it’s 6-0. I shout at him, ‘Where the f--- are you going? It’s six to nothing! What are you doing?’ Canseco starts pointing to the dugout, right to La Russa. He’s looking at me, going, ‘Yeah, it was me! I told him to go!’ So I shout back, ‘F--- you!’ A week later, I get traded to Oakland.”

Eckersley and La Russa each learned that they were both the type of person whom they’d rather play with than against.

“Tony’s become more than someone who was my manager,” Eckersley says. “He’s family, man.”

That is the type of insight that will be sorely lacking when Eckersley steps away from the game. Eck possesses a baseball portfolio that simply cannot be replicated. He battled against the great Reggie Jackson in the Sox-Yankees rivalry, then later teamed with Jefferson in Oakland during the ’87 season. He was teammates with Frank Robinson, Gaylord Perry, Carl Yastrzemski, Carlton Fisk, Rickey Henderson, Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, Tony Perez, Roger Clemens, Ryne Sandberg, Lee Smith, Jim Rice, Rafael Palmeiro, Dave Stewart, Jose Rijo, Harold Baines, Ron Darling, Rich Gossage, Dave Henderson, Scott Brosius, Dave Righetti, Jason Giambi, Ozzie Smith, Greg Maddux, Bruce Hurst, Mike Torres, Willie McGee, Jamie Moyer, Ron Gant, Gary Gaetti, Pat Borders, Rick Honeycutt, Mo Vaughn, Nomar Garciaparra, Jason Varitek, and Derek Lowe–a potpourri of Hall of Famers, World Series heroes, superstars, and, in a few particular cases, the poster children for baseball’s unforgettable steroid era. That list of teammates highlights Eck’s diverse appreciation for the cast of colorful characters who have brought baseball to life throughout multiple generations.

Clemens won a national title in college at the University of Texas in 1983. Shortly after that honor, the Red Sox selected him with the nineteenth pick in the MLB Draft. That June, he met Eckersley, as well as a host of other baseball luminaries.

“After we beat Alabama for the national championship and I got drafted by the Sox, they brought me out to see Fenway,” said Clemens. “That’s the night the cab driver dropped me off, and all I saw was this brick building. I thought we were at a warehouse. I told the cabbie, ‘I’m going to a baseball stadium,’ and he said, ‘This is it, kid.’

“The very first game I saw, if I remember correctly, the Orioles were in town and it was Jim Palmer pitching, then it was Eckersley the next night. Looking back, it was baseball royalty. That spring training, Ted Williams was there. So were Yaz and Johnny Pesky. Boggsy [Wade Boggs] was there, too, and Eck, Geddy [Rich Gedman], Hursty [Bruce Hurst], [Bob] Ojeda. That clubhouse was a who’s who.”

Celebrating his birthday on Monday at Fenway, the 68-year-old Eck was asked about some of his earliest memories of the game, including his unique leg kick on the mound.

“That’s from Juan Marichal,” says Eckersley, a product of Fremont, California who was a devoted Giants fan during his formative years. “He was my idol. That Marichal kick was everything to me. It helped me be a good pitcher right away, using my leg and making me throw harder. And I grew up listening to Russ Hodges call Giants games every night. I was eight in 1962 when the Giants played the Yankees in the World Series. Even back then, I loved following baseball. It’s been there for me my whole life.

“I was drafted by Cleveland when I was 17, and I’ve been involved with the big leagues for over 50 years. I still remember being disappointed that I wasn’t going to the Giants. Back then, you were either a National League guy or an American League guy. It’s different now. In those days, I thought the American League was second class.”

While his famed head of hair remains perfectly in place, Eck replaced his signature leg kick with a gripping take on the modern game. He effortlessly captures the brilliance of baseball’s past and present. Yet, as he reaches his peak as a broadcaster, he is opting to step away from the game.

If this retirement sticks, Eckersley is soon to fade into a baseball memory. Perhaps that respite is long overdue after living his life in a public forum. He has been on public display ever since pitching a no-hitter at the age of 22 against the California Angels in the old Cleveland Stadium. The last out was a punchout against Gil Hodges, who kept stepping out of the batter’s box before Eck could induce the final out.

“I started shouting at him, ‘Get back in the box!’” says Eckersley, reflecting on the seminal moment from all those years ago. “Think about it. It’s the last out. That wasn’t even on TV, so it’s not like you could go back and watch it. So everyone starts thinking I’m this cocky kid shouting ‘You’re next!’ to every batter. That couldn’t be further from the truth.”

Gregory Fisher/USA TODAY Sports

Since then, Eckersley’s hair has grayed. He stopped drinking decades ago, finding new ways to bring out the best in himself, and his perspective–like a fine wine–has continued to evolve and mature. A proud grandfather, he now moves on to his next challenge.

But baseball has a quirky way of coming full circle. No longer the brash young kid shouting at a batter to get back in the box, it is the game hollering at Eckersley to return to the booth. The idea of baseball without Eckersley is an untenable notion, and it is absurd to think a network won’t swoop in and make Eckersley part of their national broadcasts. Unless it is too late.

“It’s just time,” Eckersley says. “It’s my time to go.

“But it’s sad. When I think back, I remember all the bad stuff. Luckily, I had a lot of good stuff, too. But even with a Hall of Fame career, I really remember the bad stuff. You know why? It was painful. It meant something. Pain sticks longer than joy.”

Baseball isn’t supposed to be easy or full of accolades and praise. It is a grind, an unrelenting-yet-often-impossible pursuit of greatness. Eckersley understands. He knows what the world looks like from above the mountain top just as well as the view from the bottom.

Eckersley forever left a lasting footprint on the game. If this is it, then goodbye to a unique perspective and farewell to a vernacular unlike any other. Parting is such sweet sorrow, a Shakespearian aphorism especially true in this setting.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done,” Eckersley says. “It took a lot of guts. I could have just hung out. I’m proud I did it. Maybe I’ll finally think of all the good stuff now.”