A few weeks ago, the Food and Drug Administration dropped a huge project in the lap of the American Red Cross: Help sign up enough people to donate plasma rich with COVID-19 antibodies to treat more than 6,500 patients clamoring for infusions via a fast-growing network of hospitals and clinics nationwide.

But weeks later, there’s just not enough plasma to go around. Only 3,000 people—less than half of patients signed up—so far have received transfusions.

“We don’t have enough donations to meet demand,” said Dr. Matthew Coleman, a physician based in Tusla, Oklahoma, who serves as the medical director for the American Red Cross region that includes Texas. Coleman told the Observer: “We’re ramping up donations as quickly as possible, [but] we have a backlog of requests.”

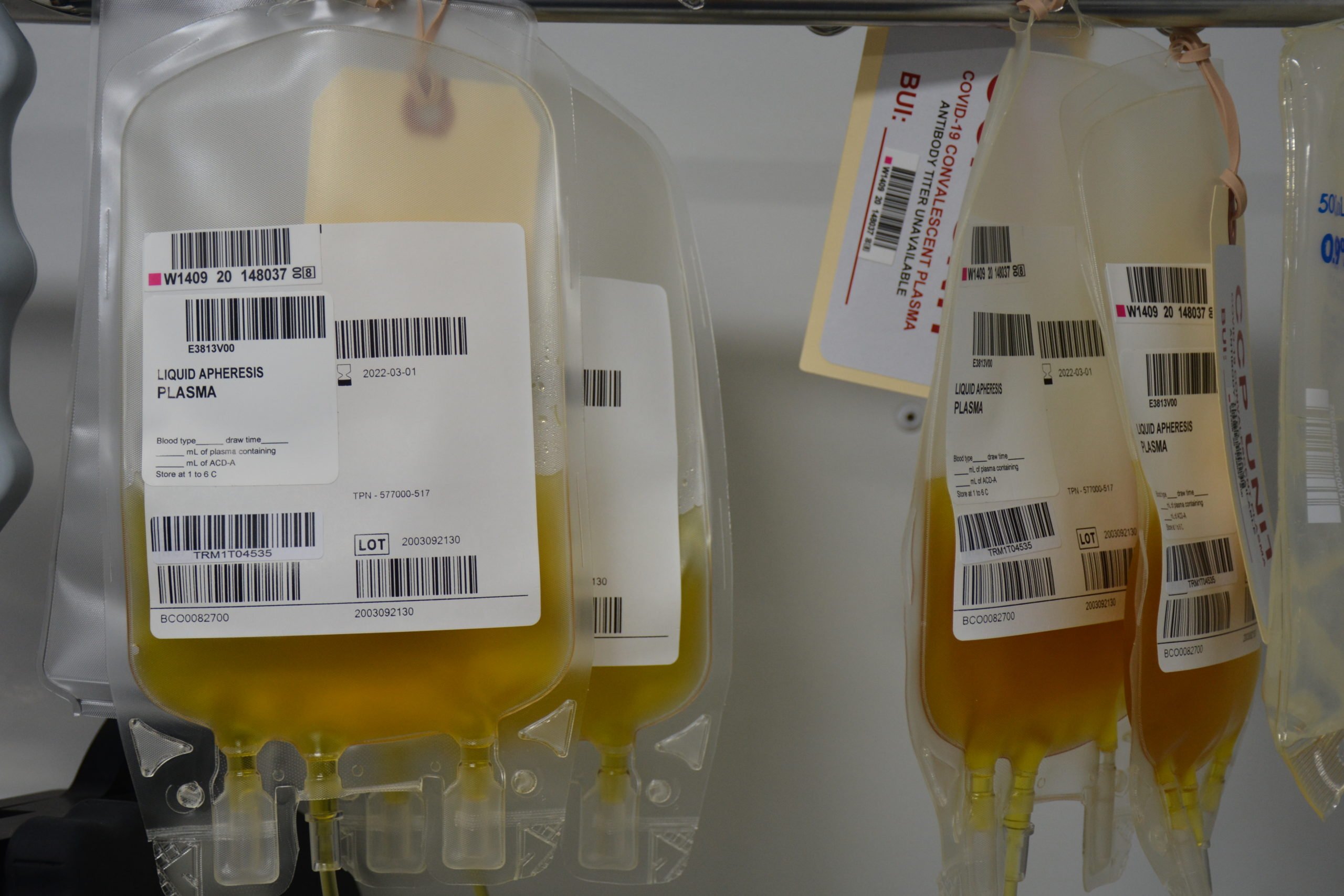

The first Texas patients received plasma therapy on March 28 at Houston Methodist Hospital, part of a group of leading research hospitals that self-organized to use plasma from recovered patients to treat the sick. It’s a technique that saved lives in previous pandemics, including the deadly flu of 1918, though only limited studies from China demonstrate its efficacy against COVID-19.

Despite the lack of proof, the grassroots plasma project grew to more than 1,000 participating sites in the first two weeks of April. As of today, that has doubled to more than 2,000 sites, with 6,563 registered patients, according to data collected by the Mayo Clinic, which is tracking progress of the ongoing effort.

Nationally, the Red Cross has quickly recruited plasma donors, too. As of Monday, the nonprofit had collected 30,000 names. In the multistate region that includes Texas, the nonprofit had collected only approximately 435 units of plasma, Coleman said. That’s not nearly enough to meet demand in Texas alone.

Statewide, at least 100 hospitals are participating in efforts to treat COVID patients with transfusions of plasma from those who have recovered, according to a tally by the Observer. Many of those hospitals are part of large chains, affiliated with religious organizations or elite medical schools, but the network also includes public hospitals that serve the poor, like Ben Taub in Houston.

But few hospitals, like Houston Methodist, are able to collect plasma from their recovered patients and then provide transfusions to those waiting in their ICUs.

Meanwhile, the list of sick patients waiting for infusions of plasma with disease-fighting antibodies continues to grow. Priority is given to the sickest or those who have underlying conditions that make them particularly vulnerable.

The nationwide efforts are being overseen by Mayo Clinic researchers, who remain encouraged by anecdotal evidence of improvement. There are no immediate plans to publish results. In a video, Dr. Michael Joyner, the Mayo Clinic head researcher, says the hope is that the trickle of donated plasma “will grow into a river in the coming weeks. But the logistics on this are going to be very, very challenging.”

All donors must be able to prove they’ve been diagnosed and recovered from coronavirus. That means that only some of the first Texans to be infected (and tested) could potentially qualify. “The current efforts mean we need to reach toward the beginning of the pandemic,” Coleman said.

Unfortunately, antibody tests, which have been approved by the FDA, are not yet available to the Red Cross or Texas blood banks to screen other potential donors who had coronavirus symptoms but were untested. That may soon change, as some private Texas clinics have been able to obtain these tests. “We are accepting [people] with positive results from FDA-approved antibody tests,” said Nick Canedo of We Are Blood, a large Central Texas blood bank. “But we can’t facilitate [antibody tests] for donors, as they are not yet available to us.”

We Are Blood, which supplies a network of 40 hospitals, collected its first plasma donation on April 8. So far, it has received more than 180 applications from potential donors, but has been able to collect plasma from only 40 of them, Canedo told the Observer. Canedo said that’s enough to meet demand for plasma for COVID-19 treatment because only six Central Texas hospitals are offering it so far.

Another issue thwarting the pace of potentially life-saving plasma treatments is that the Red Cross of Texas lacks equipment: It can collect whole blood, but not plasma alone. Instead, the nonprofit is using its website to recruit and screen potential donors and refer them to sites within 100 miles of their homes.

In Houston, Troy Chandler was one of the first to donate at Houston Methodist Hospital. In Austin, Henry Groppe was among the first donors at We Are Blood, while in San Antonio, David Hermann was the first to donate at the South Texas Blood and Tissue Center. (As of today, the center was preparing to take plasma from its 100th donor.)

Hermann came down with a mild case of COVID-19 after a ski trip to Crested Butte, Colorado, in March. He said he felt lucky to have recovered quickly and was eager to contribute. “I felt like it was the right thing to do to give back to the community,” Hermann said.

Find all of our coronavirus coverage here.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Mi Barrio No Se Vende: San Antonio is planning to demolish its oldest and largest public housing project, threatening the future of a deeply historic neighborhood—one that anchors the city’s identity as the nation’s Mexican American capital.

-

From Jail to the Streets: One Texan’s Story During COVID-19: The homeless are 11 times more likely to be incarcerated than the rest of the population.

-

‘I’m in Limbo Here’: Texans Are Met with an Overwhelmed and Antiquated State Unemployment System: The safety net meant to support the second largest workforce in the country is using decades-old technology. The workforce agency was trying to replace it when the pandemic hit.