As has always been the case with any technological development, most common discussions around Artificial Intelligence (AI) centre on the direct, perceivable pros and cons it poses (thanks to sci-fi’s favourite plot of robots taking over all humanity). It takes an unfortunate scapegoat to force us out of our voluntary or involuntary ignorance, look at everything that lies beyond, and acknowledge the gaping divide between those who are willing and not willing to participate in AI-related discussions.

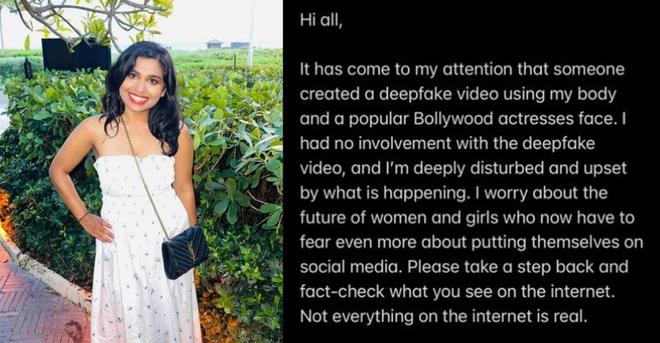

Earlier this month, a deepfake video (a video featuring a human whose appearance was digitally altered using AI tech) surfaced featuring Rashmika Mandanna’s facial likeness morphed over that of British-Indian social media personality Zara Patel. While those familiar with deepfakes could spot its eeriness immediately, Rashmika’s pan-Indian popularity, the fact that she was the first Indian actor to voice out against deepfake abuse, and that it got even the Prime Minister voicing out his concerns, attracted colossal media attention. The only silver lining in the controversy that erupted is that it has demanded that social media users from India pay attention to the global conversations on both AI as well as the regulation of the use of the tech in the hands of humans.

For most of us, the allure of AI applications has certainly made scrolling through social media a fascinating exercise. Who would have ever thought one could listen to ‘Ponmagal Vandhal’ in the voice of PM Narendra Modi? The Rajinikanth and Silk Smitha of the ‘80s came alive in a video tribute, and we even heard a recent Rajini song sung by the late S. P. Balasubrahmanyam.

What grabbed the most eyeballs was a deepfake video of the ‘Kaavaalaa’ song from Jailer that had Tamannaah Bhatia’s face swapped with that of Simran. Both the actors appreciated the AI rendition, but if you are wondering why we were largely made aware of AI through entertainment media, Simran reminds us that it has always been the case. “I believe it’s one way, it seems, the creators of AI are letting the world know of their presence,” she says.

But there’s a vital, high-risk aspect of deepfakes that makes systems established to tackle pre-existing cyber-crimes like morphing and revenge porn — the sadly normalised forms of cyber-attacks that female public personalities are often subjected to — seem redundant. Because the threat is no longer just a photo being morphed onto another photograph or a non-consensual upload of demeaning private media. What we are discussing is also the product of generative AI that can create something new, almost perfect renditions, with what it has been fed. The baffling rate at which generative AI is advancing makes the Rashmika controversy seem almost mild in comparison to what the future holds.

Awareness and vigilance

What we are discussing is a minute aspect in the gamut of AI — misuse of generative AI, by humans, for personal attacks. The Indian government has been vigilant in implementing measures to tackle AI-related issues since before the term became a parlance and measures combating Dark AI are being developed every millisecond globally. But what resolution exists for victims of deepfakes currently in India?

Say a deepfake video featuring your digital likeness was released online. The first step pundits advise you to do is to report the post to the social media platforms, which are legally bound to not only address grievances relating to cybercrime but specifically in this case, remove it within 36 hours. Ashwini Vaishnaw, the Union Minister for Electronics and Information Technology and Communications, held a high-level meeting with social media platforms and professors pioneering in AI to discuss measures to tackle deepfakes.

ALSO READ: AI-generated child sexual abuse images could flood the internet; UK watchdog calls for action

The wait for proper legislation that directly addresses deepfakes and AI-related crimes is awaited, but meanwhile, the internet and law enthusiasts are happy to help you in guiding you with legal recourse. They say it’s best for a victim to lodge a complaint with the National Cyber Crime Helpline — 1930. Avail the services of a good cyber lawyer who would explain the many provisions of Section 66 of the Information Technology Act of 2000, the Copyright Act, and other provisions under the Indian Penal Code that can provide legal remedies. If the nature of the deepfake or any morphed picture is intimate (or even if any intimate image was posted without consent), victims can avail help at the online forum stopncii.org which also promises to safeguard privacy.

But is there anything else that can be done to prevent such content from reaching unaware consumers? Imagine what would happen to WhatsApp Universities if — like Facebook’s and X’s fact-checking tools — social platforms could help sort through AI content. It might be possible for the source post but what about the media files that are duplicated and forwarded? If only we knew of a machine that could be trained to relentlessly fight any duplication.

Fighting AI with AI

AI models are being developed to counter Dark AI activities and one can only hope for more open-source tools — in the same vein as Nightshade, which when applied can slightly tweak the digital artwork in the back end, making it hard for AI models to train themselves on — to first prevent misuse of our social media images, and second, alert consumers when they come across an AI-altered media. A simple Google search on how the tech world is combating deepfakes with AI lends many fascinating results, like Intel’s deepfake detector called FakeCatcher, which is said to spot ‘blood flow’ in the pixels of a video (measures how much light is absorbed or reflected by blood vessels) to detect deepfakes. There have been other notable measures in providing transparency in the use of AI, like the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), an open technical standard created by the coming together of many software companies with an aim to authenticate digital pictures. We must not forget that in the aforementioned deepfake controversy, there were two victims — Rashmika Mandanna, and Zara Patel. It’s no news that actors and social media influencers, particularly women and other marginalised genders, are unfortunately forced to face the brunt of deepfakes and other cyber crimes, and there is no support system in place to guide them.

Even if not for personal attacks, the recently held Hollywood strikes have proven that Indian cinema lacks a national union like SAG-AFTRA, the union for Hollywood actors, to take a stand against the potential use or abuse of AI by studios that can threaten the livelihood of actors. Simran agrees as well. “The bad side of AI is really nasty but the good side is that we all know about the worst side of it.”

For now, there’s little we can do other than be aware of new AI tech and measures to combat Dark AI, and let legislature, AI scientists, authorities, and human-friendly AI models do their jobs.