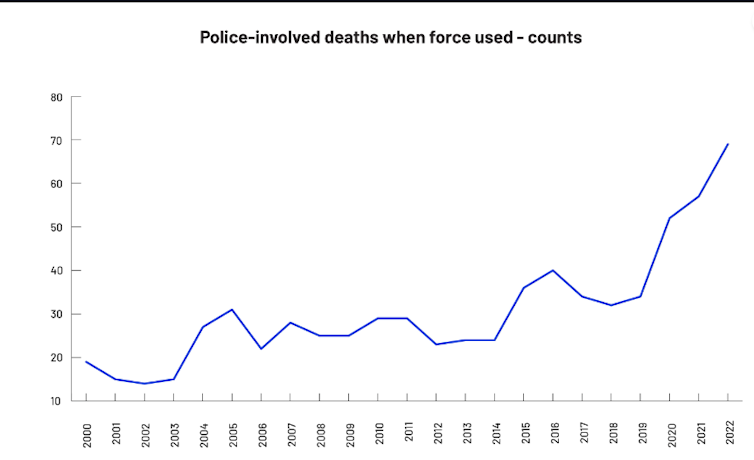

Fatal encounters with police are on the rise in Canada. The number of civilians dying in incidents with police when force is used has steadily increased since 2000. This is leaving families and communities with little support or recourse for accountability.

We are members of the Tracking (In)Justice project documenting and analyzing police-involved deaths when force is used in Canada. Tracking (In)Justice is a partnership of academics and advocates who aim to shed light on police violence to help inform calls for accountability, transparency and changes to policing.

Gathering this information gives us the ability to ask new questions, such as why some police forces kill people more frequently than others. It also allows us to inform policy designed to address issues of police accountability.

There have been longstanding calls for police and governments to collect and share data about incidents where the use of force caused civilian injury and death. Journalists, academics, civil society groups and victims’ families have been engaged in this work for a long time.

However, no centralized, updated data set exists that tracks deaths and provides information about the person, location, implicated police service, type of force used and many other contextual details. Much of what we rely on to understand these cases are “official” documents like police or oversight body media releases, that contain limited details and only tell a one-sided police narrative.

Tracking fatalities

Our preliminary findings indicate that use-of-force incidents are on the rise, with the highest number occurring in 2022. Some of this long-term trend may be due to increased access to information about police-involved killings and deaths. But access to information alone does not explain the striking increase in recent years.

According to Tracking (In)Justice data, there was an average of 22.7 police-involved deaths between 2000-2010. In comparison, an average of 37.8 people died every year between 2011-2022. That represents a 66.5 per cent increase.

Shooting deaths also appear to be occurring with greater frequency. Tracking (In)Justice documented 704 deaths in Canada from 2000 to 2022 where police force was used. The data includes deaths from police shootings and instances where a person died after being subjected to other types of police weapons (e.g. tasers) or physical interventions (e.g. restraints).

This data was compiled by accessing publicly available information from media and official reports. The data includes information related to the victim, including name, age and race when known. It also documents the location of death, involved police and the highest level of force used.

Tracking racial data and shooting deaths

Following longstanding patterns of inequity, there are persistent racial disparities within the overall increase in police-involved deaths when force is used.

According to the data we’ve collected, Black and Indigenous people are killed at disproportionate numbers relative to their population size. According to the most recent Statistics Canada census data, Indigenous people make up 6.1 per cent of Canada’s population and Black people comprise 4.3 per cent.

Tracking (In)Justice data shows that 112 of the deceased were identified by police or other authorities as Indigenous, and 54 were identified as Black since 2000. These numbers represent 16.2 per cent and 8.1 per cent respectively. More than 240 people were identified as white. However, it should be noted that a significant number of unknowns exist, as race is often not reported on public documents.

Racial disparities are further reflected in the numbers specific to police-involved shooting deaths. People identified by police or other authorities as Black represent 8.7 per cent of the total number, while people identified as Indigenous represent 18.5 per cent.

Together, Black and Indigenous people comprise around 10 per cent of the population in Canada, yet account for 27.2 per cent of police-involved shooting deaths when the race of the victim has been identified.

Deaths by jurisdiction and police service

Most provinces and territories have seen increases of 30 per cent or higher in police-related deaths since 2010.

Overall, Ontario has the most deaths at 224, followed by British Columbia at 141, Alberta at 121, Québec at 115, Manitoba at 38 and Saskatchewan at 29. The remaining provinces and territories have experienced nine or fewer deaths since 2000. New Brunswick and Nunavut experienced one death each between 2000 and 2010, followed by a spike of seven deaths each between 2011 and 2022.

Three police services — Toronto, Peel and Montréal — were implicated in two-thirds of the deaths of Black-identified people. The RCMP is implicated in more than half of Indigenous deaths, at 57 out of 112. Some of this long-term trend may be due to increased access to information about police-involved killings and deaths. But access to information alone does not explain the striking increase in the past three years.

Calls for accountability

Tracking (In)Justice is a living data set and a work-in-progress. We are actively working to expand the data, including identifying whether the person killed was labelled by police as a “person in crisis.” This is a problematic and ableist category, which may give us insight into the ways people labelled with disabilities are impacted by police violence.

The data also does not include incidents where police were present, but force was not necessarily used, such as during falls, vehicle crashes or deaths in custody.

What is also missing is the impact on families when their loved one is killed by police. When someone has a family member killed, they cannot access victim services, as the loved one is not considered a victim. They may never know the name of the person responsible for killing their loved one and may have to pay out-of-pocket legal fees in their efforts to seek justice.

Family members may also never get access to coroner’s reports, oversight investigation reports or even their deceased family member’s belongings. They are often unjustly provided little assistance to navigate systems in their pursuit of justice.

There is increasing attention being brought to bear on police violence and racial injustice in the Canadian criminal justice system. Our project’s findings support long-standing calls for accountability, transparency and scrutiny of police conduct in Canada. Much more work still needs to be done.

Andrew Crosby receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Alexander McClelland receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Tanya L. Sharpe receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Anti-Racism Directorate, Ministry of the Solicitor General.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.