When the Philadelphia Eagles and Kansas City Chiefs take the field for Super Bowl LVII, a record-breaking 50 million bettors are expected to have US$16 billion of their own skin in the game, according to the American Gaming Association.

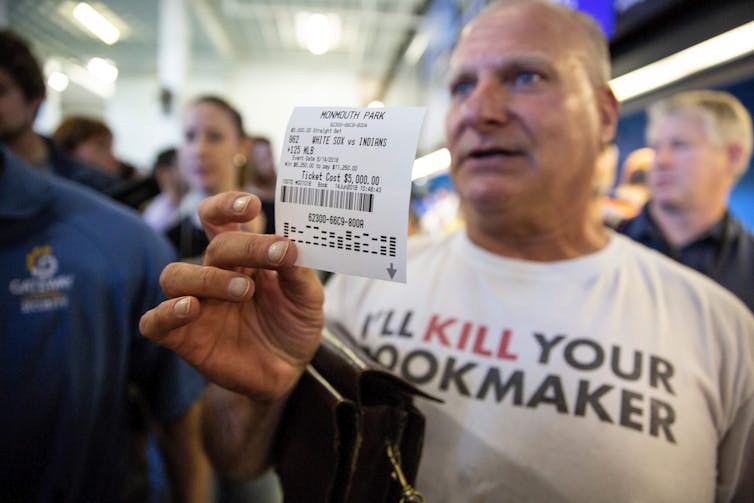

In January 2023, Ohio and Massachusetts launched legal sports betting, joining Washington D.C. and 34 other states that have passed laws since the Supreme Court overturned a federal ban in 2018. State legislatures have generally been eager to capitalize on the tax windfalls from sports betting and get their slice of the billions wagered annually. Voters are also increasingly supportive of legalization.

Here in New Jersey, sports betting, both online and in person, has been legal since June 2018. The state is the only jurisdiction that requires yearly evaluations of the relationship of online gambling and sports wagering to problem gambling.

The Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University, which I direct, conducts those annual evaluations using data from all sports bets placed in New Jersey since 2018. Our findings suggest that the nation’s love affair with sports betting may be having unintended consequences.

Sports betting tied to poor mental health

In a forthcoming statewide gambling prevalence study, we found that those wagering on sports in New Jersey were more likely than others who gamble to have high rates of problem gambling and problems with drugs or alcohol, and to experience mental health problems like anxiety and depression. Most alarming, findings suggest that about 14% of sports bettors reported thoughts of suicide, and 10% said they had made a suicide attempt.

A small group of bettors seem to be most at risk. About 5% of all sports bettors placed nearly half of all bets and spent nearly 70% of the money. That means the people losing the most money are the most essential to operator profits.

The fastest-growing group of sports bettors in New Jersey are young adults, ages 21 to 24. Most have placed in-game bets, and about 19% spent half of their money betting during games, when emotions and impulsive spending are highest.

Although regulators require operators to allow bettors to set limits – on losses, deposits or time spent gambling – only about 1% of young bettors use any of the safeguards, less than any other age group. Since about 70% of the sports bets we analyzed were losing bets, most of these young players could find themselves losing more money than they can afford.

A vulnerable population

It is possible, then, that states could unwittingly be introducing a cohort of young people to problem gambling and a lifetime of negative consequences.

That’s because the younger that people start gambling, the more activities they bet on. And the more frequently they bet, the more likely they are to develop serious gambling problems. Studies suggest that those who gamble as young adults have higher-than-average rates of problem gambling.

The danger is compounded by the easy access afforded by tablets and mobile phones, which eliminate most barriers to gambling even for those who are underage. Children who are exposed to the unrelenting parade of gambling ads report they remember both the products and the betting terms from those ads, and some teens say they intended to gamble as a result. If parents or other household members also gamble, those children may later develop not only gambling problems, but also problems with drugs and alcohol.

Few regulatory measures in place

In the U.S., the Marlboro Man can no longer gallop across the nation’s television airwaves. Alcohol ads can’t contain statements that are misleading, patently false or target those who are underage.

However, there are currently no such federal guidelines for gambling ads. Major League Baseball, which banned Pete Rose and locked him out of the Hall of Fame for gambling, openly sanctions sports books attached to stadiums and partnerships with gambling operators. The same goes for the NFL and most of its teams, with former stars like Eli Manning encouraging betting in ads and Pro Bowl wide receiver Davonte Adams becoming the first active player with a gambling sponsor.

Those who recognize they have a gambling problem also have no assurances that they can find help.

Gambling treatment services vary by state, from specially trained, culturally competent counselors in a few states to a total lack of services in others. Most children and teens receive no education in schools about problem gambling as they do for drugs and alcohol. Some universities are openly partnering with gambling companies and sponsoring esports competitions, which invite underage betting.

The federal government is noticeably silent on a glamorized addiction. Nationally, there are no federal policies, prohibitions or federally funded research or prevention programs, despite all the revenue generated by taxes on gambling winnings.

Internationally, gambling-related abuses and tragedies have led countries like Australia and the U.K. to enact new regulations and significant penalties for operators. The U.K., for example, requires operators to conduct affordability checks on patrons to ensure they can afford their losses and prohibits gambling advertising by athletes, celebrities or social media influencers who appeal to children and teens.

I think it’s only a matter of time before similar proposals make their way to the U.S. In the meantime, however, millions of people in more than half the country will legally lay their hard-earned money on the line for a chance to win big on Sunday.

Hopefully, they can afford to lose.

Lia Nower has been a member of advisory boards, and has conducted research and grant reviews for U.S. and international governments, government-related agencies, private firms, and industry operators. These include New Jersey's Division of Gaming Enforcement & Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Ohio's Department of Mental Health and Addiction, Camelot (United Kingdom), Crown Casino (Australia), the British Columbia Lottery Corporation (Canada), Churchill Downs (U.S.), Aristocrat Leisure (Australia), the New York Council on Problem Gambling, Publiedit (Italy) and the National Council on Problem Gambling (U.S.).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.