Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, first published in 2014, represents that rare bird in small press and independent publishing in Australia: a long-term sales success.

Dark Emu attempts to debunk the idea that pre-European Aboriginal people were purely “hunter-gatherers”.

Indeed, it suited settler-colonists, Pascoe argues, to fail to recognise Indigenous agricultural practices as organised, intelligent land management. In the original publisher’s press release, Pascoe described it as a book “about food production, housing construction and clothing”.

By mid-2021, seven years later, it had sold an impressive 250,000 copies.

But sales are just one way to demonstrate the success, or value, of a book.

Measuring value beyond sales figures

We tracked the impact of the original edition of Dark Emu over five years, from 2014 to 2019, to look at how it contributed to (or otherwise altered) six categories of value, or “capital”. They were: financial (the primary way our culture measures a book’s success), but also social, human, intellectual, manufactured and natural.

We borrowed these six categories from a value-reporting mechanism used in the corporate sustainability sector, The Integrated Reporting Framework.

Dark Emu was one of around 20,000 books published in Australia in 2014. Most of these works would have been aimed at a modest market, with print runs of between 2,000 and 4,000.

By 2016, Dark Emu was reported to have sold more than 100,000 copies. Many local releases all but disappear from bookshop shelves within a few months of their release. But instead, Dark Emu gathered slow momentum.

Five years later, in 2019, it reportedly sold 115,300 copies in Australia and New Zealand in a single year.

Impact on manufacturing

Manufactured capital looks at the physical object that’s been created. In this case, that’s the first-edition physical book of Dark Emu, as well as subsequent physical objects generated by or through it (including reprints).

Between 2014 and 2019, Dark Emu was reprinted 28 times. It was also produced as an e-book and an audio book.

By 2017, world rights were sold to Scribe, which published North American and UK editions in 2018. An edition for younger readers was released by its original publisher, Magabala, in 2019. Magabala also published at least one secondary text: a resource for secondary school teachers, Dark Emu in the Classroom.

We tracked the significant impact on manufacturing from this single book title as it was reproduced in various forms, showing evidence of its impact across a range of allied book industry sectors – especially the print industry – both in Australia and internationally.

Supporting Indigenous creators

In the five years immediately following the release of the original edition of Dark Emu, it accumulated considerable intellectual capital.

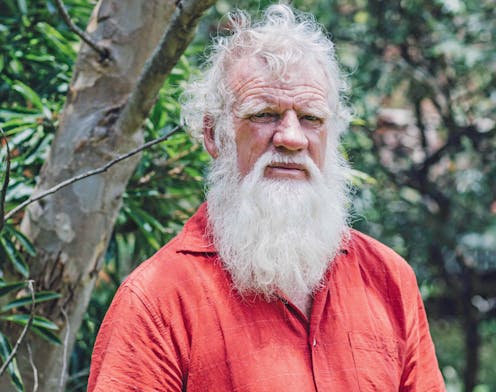

Numerous arts and literary sector awards recognised the book’s outstanding public, literary and cultural value between 2014 and 2019. This recognition culminated in Bruce Pascoe being awarded the Australia Council for the Arts Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature in 2018.

The publication of Dark Emu had a significant impact on its small not-for-profit publisher, Magabala Books. Founded in 1984, Magabala is Aboriginal owned and led, and focuses on celebrating and nurturing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices.

After Dark Emu was published, Magabala expanded its publishing program.

Magabala was shortlisted for Small Publisher of the Year at the Australian Book Industry Awards in 2017 and 2019. That second year, it was also the fastest-growing independent small publisher in Australia.

Magabala also invested in philanthropy. Its Creative Development Scholarship to “support professional development relating to writing, illustration and storytelling” for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander storytellers, writers, illustrators and artists supported 27 scholars between 2014 and 2019.

Dark Emu created jobs in the performing arts, too.

A dance adaptation by Bangarra Dance Theatre premiered at the Sydney Opera House in 2018, involving more than 30 arts workers. Program notes for the national tour list three choreographers, 17 dancers and a production team of six, as well as 11 musicians and a composer employed to work on the production.

In 2019, Screen Australia announced a documentary series would be developed based on the book. While delayed by COVID-19, the series is still in production.

New understandings of Australian history

To measure the book’s social impact, we focused on how it contributed to the human rights, health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in Australia, as well as how it contributed to broad public understanding of Australian history.

Then we looked at how the book increased public debate. (We should note, we didn’t include Peter Sutton and Kerry Walsh’s 2021 book rebutting Dark Emu, Farmers or Hunter-gatherers?, as it was beyond the scope of our study: our research spanned 2015-2019.)

Digital forums provide short, sharp narratives that bring qualitative value into focus. (So-called “parables of value”.)

On Booktopia, many hundreds of readers reviewed Dark Emu; 86% of them gave the book five stars, reflecting its broad popularity. This selection of Booktopia reviews speaks to the way Dark Emu contributed to new understandings of Australian history:

A marvellous book, full of information and insights which were new and fascinating to me. Well researched and well written. It should be compulsory reading for all Australian schoolchildren.

Super interesting and I wish I’d been taught more of this earlier in life.

I have only just started using this resource for my Year 9 class […] It has thus far provoked conversation and questions. It is particularly interesting as we live in an area that Major Mitchell explored, and there are numerous tracks etc named after him. Always interesting [to be] given the other side of history.

I couldn’t stop thinking about this book […] after reading it and going through any bush in Australia you see the landscape very differently.

Our analysis identified an extraordinary degree of public debate generated by the book – in part because it soon provoked another chapter in the “Australian History Wars”.

Social commentator Andrew Bolt, for example, published several columns on Dark Emu in the Herald Sun during 2018-19. He drew heavily on an anonymous website, Dark Emu Exposed, which purports to “expose” and “debunk” what it asserts are the book’s many myths, exaggerations and “fabrications”.

Interestingly, Russell Marks links the extraordinary sales success of Dark Emu in 2019 directly to the increase in public debate fuelled by Bolt.

Read more: How the Dark Emu debate limits representation of Aboriginal people in Australia

Environmental impacts

It is not possible to precisely measure the air, water, land, minerals and forests required to produce and distribute Dark Emu. But we were able to make some informed estimates.

Figures from an overseas study found that the paper required to produce 100 books requires about one tree. On this basis, copies of the original Dark Emu title sold in Australia in 2019 consumed the equivalent of 1,153 trees.

Other sources estimate the carbon footprint of a single book is 2.71 kilograms carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂ equivalent). On this basis, Dark Emu’s sales in Australia in 2019 could be said to have produced 312,467kg of CO₂ emissions. That’s the equivalent of emissions produced from 5,002kg of beef – or, the amount of beef consumed by 200 Australians in an average year.

But unlike many other Australian books, Dark Emu has not just consumed natural capital: it has also contributed to it.

With earnings from his royalties, Pascoe purchased farmland in regional Victoria. There, he is applying knowledge gained through research for the book to regenerate the local ecology, using Indigenous agricultural practices. He says:

The farm I’m working on, I got rid of the cattle and within a season the grass was knee-high again. And areas that had been cut, that should never have been cleared at all, where they were showing their bones through the soil, they’ve come good again.

Pascoe’s appointment as Enterprise Professor in Indigenous Agriculture at the University of Melbourne makes likely further positive contributions to natural capital: via teaching and research in Indigenous land management. All traceable to a single book title.

Why do we measure value beyond money?

In a capitalist world, it sometimes seems like the almighty dollar is the only marker of value. So many conversations about value stem from that single category – but there’s far more to it than that.

Our interest in value in relation to Australian books is informed by multiple disciplines that together enable a more holistic conceptualisation of value. From cultural economics, a sub-discipline of economics concerned with the economic analysis of the arts and culture, researchers like David Throsby distinguish economic value from cultural value.

Arjo Klamer is a Dutch cultural economist whose valued-based approach has been described as advocating “humanonics” (economics with humans and meaning left in). His work helps us consider the impact of the environment around us on how and why things become valued as social and cultural practices.

He cautions that attempting to measure the value of culture in purely quantitative terms invokes the “Heisenberg principle of economics”: what is measured impacts how value is perceived. (So, for instance, measuring the value of Dark Emu in terms of its sales alone ignores other “value dimensions” that are generated.)

In the discipline of sociology, Pierre Bourdieu describes how cultural fields are shaped by symbolic capital. To use the field of book production as an example, writers or publishers accrue symbolic capital through markers of prestige, such as when their books receive favourable reviews or win prizes.

John Frow further explains that the value of cultural objects is derived from their use in different contexts (or “regimes of value”).

For example, within the Australian tertiary education sector, a cultural object like an Arts degree has value it would not have in another industry. And a book might be chosen for the Australian school curriculum based on aesthetic principles (like the quality of its prose), but also on criteria such as its depiction of a particular idea of Australia, or its relationship to other parts of the curriculum.

The national value of Australian books

What do locally written and produced books contribute to Australian life?

At a time of national cultural policy renewal – and as so many Australian authors struggle to survive financially – our preliminary work with Dark Emu shines light on this question.

Our research shows how Australian books circulate in our culture and what they bring – not just in dollar terms, but across a range of other important dimensions.

It’s the kind of work – collecting data relevant to our local book industry – that many contributors to last year’s national consultation on a new Australian cultural policy have called for.

This investment is urgent, with the new cultural policy, Revive, sending a strong message that Australian authors and literature have a vital role to play in “telling Australian stories”. The evidence for gauging policy success over time will need to be broad – beyond measures of economic impact alone.

We need data that will complement and help contextualise the economic indicators of a book’s success, through an expanded frame of reference.

These additional indicators might include health and wellbeing, social inclusion and educational value, and the contributions a book makes to place-making and truth-telling.

Dark Emu is an extraordinary book. In many ways, it’s one of a kind.

But our work in measuring Dark Emu’s impact over a five-year period offers interesting future possibilities. Possibilities for how we might measure and articulate a broader set of value dimensions in relation to Australian books. The question of what a book might really be worth can – and should – be answered across multiple dimensions.

Julienne van Loon has been a recipient of funding from Creative Victoria, ArtsWA and the Australia Council for the Arts. She is a member of the Australian Society of Authors.

Bronwyn Coate has been a recipient of funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the Australia Council for the Arts. She is currently the Executive Secretary/Treasurer for the Association for Cultural Economics International (ACEI).

Millicent Weber does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.