Vandalism on the railway can result in a life sentence and an unlimited fine for the perpetrator. But the act of national vandalism that is the decision to disconnect the North completely from HS2 will mean a life sentence of inadequate rail services for tens of millions of travellers across England, Wales and Scotland.

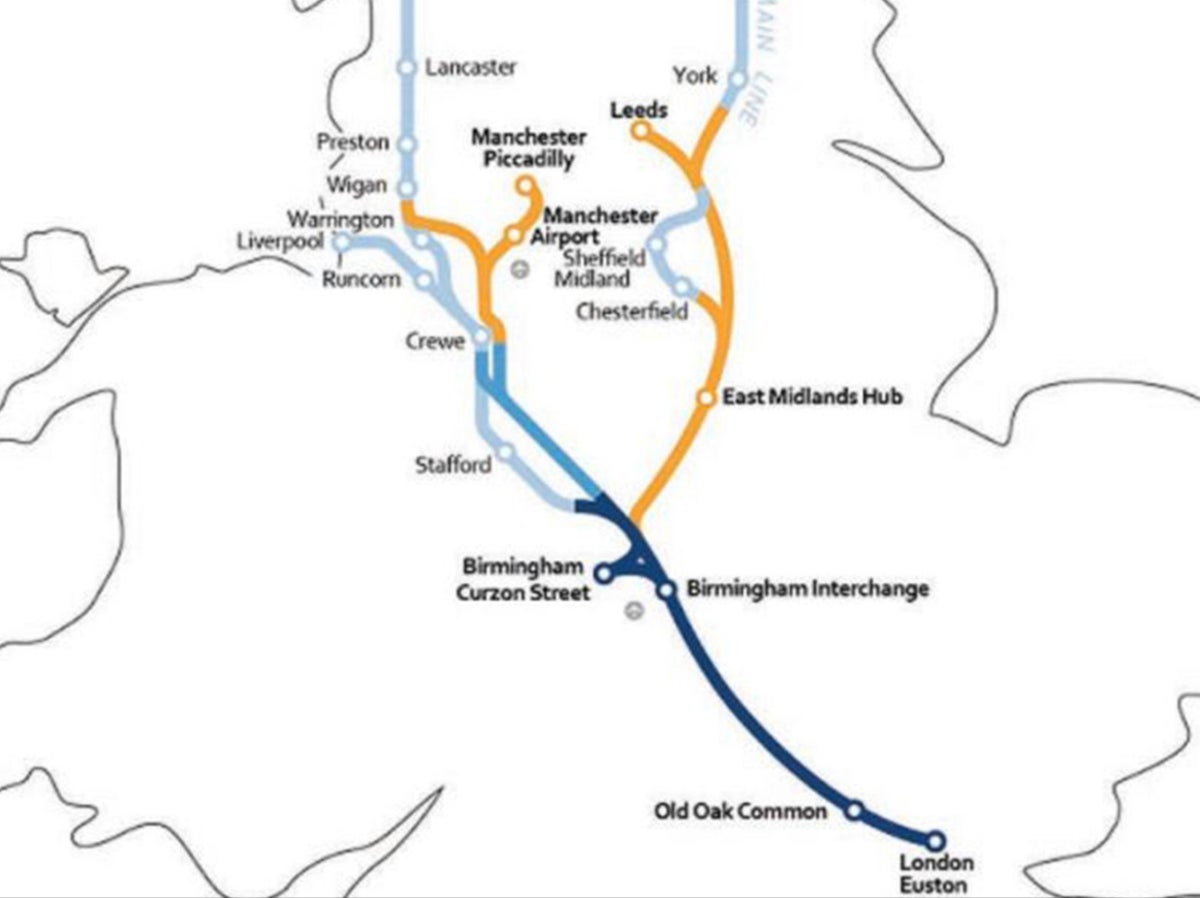

No serious figure in the rail industry can believe what the government is contemplating: ripping up the primary function of HS2. The line as conceived (and as recently as two weeks ago, guaranteed by a future Labour government) is designed to connect Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield and Nottingham with Birmingham at 21st-century speeds.

The onward link to London is intended to provide vital extra capacity on all north-south services, with the valuable side effects of slashing journey times and tempting travellers from road to rail.

The proposal to leave just a link between Birmingham and a patch of wasteground in west London is mind-bogglingly crazy. An “Old Oak Common to Birmingham shuttle” trashes the tangible benefits, and will endure for the rest of the century as a bizarre monument to incompetence and short-termism.

The best way to demonstrate the damage that ministers appear to be about to commit is to look at the prospects for individual passengers.

Take the traveller from Manchester heading south. The journey to the West Midlands will remain as slow and congested as it is now. The western leg had the prospect of all the intercity passengers transferring to high-speed expresses to Birmingham and on to London.

If the embarrassing route of London to Birmingham is all that survives the death by 1,000 cuts, it will deliver zero benefit to Mancunians. The current Trent Valley route, cutting across the north Midlands and avoiding Birmingham, will be the only rational path – otherwise high-speed trains would need to crawl through the West Midlands from Wolverhampton to the HS2 terminus.

Travellers from Stafford, Crewe, Liverpool, north Wales, Lancashire and Cumbria will also be no further ahead.

From the east of the Pennines, the picture looks even worse. The Leeds-Sheffield-Birmingham leg of HS2 was the limb set to deliver the greatest economic and social benefits. Leeds to Birmingham plus Sheffield, Nottingham and Derby to London are intercity journeys that, in any rational nation, would be high-speed electrified routes. That was the vision of HS2.

Grant Shapps’s now-disintegrated Integrated Rail Plan, published under two years ago, criminally damaged the eastern leg – leaving just a stump heading from Birmingham towards East Midlands airport. But at least it would have delivered some benefits, in adding capacity, reducing congestion, and accelerating journeys even for those travelling from Kettering, Bedford and Luton to London.

That is because the current 125mph expresses devour capacity on the network the Victorians bequeathed us. Local, regional and freight services are all constricted so that passengers can travel between Sheffield and London in two hours. Get them off the tracks, and connectivity is transformed.

Then there is the East Coast Main Line: the flagship route connecting London King’s Cross with Yorkshire, northeast England and Edinburgh.

At its southern end, signallers face a daily battle to thread commuter services from Cambridge to the English capital into an endless succession of intercity trains from the Scottish capital, east and West Yorkshire on four different operators: nationalised LNER in competition with “open-access” firms Lumo, Grand Central and Hull Trains.

HS2 should have funnelled most intercity journeys from Yorkshire, County Durham, Tyne & Wear and Northumberland into the high-speed marvel, easing the squeeze further south.

Mr Shapps, who at the time was transport secretary, damaged his constituents’ interests when he took an axe to the eastern leg of HS2: the people of Welwyn and Hatfield will not have the commuter links they deserve, because capacity will continue to be reserved for the expresses.

Until now, Scottish passengers knew that they would derive some modest benefit from HS2 on journeys to the Midlands and London. They rightly felt aggrieved when the “Golborne spur” was cut.

This vital high-speed link was to take HS2 through the tangle of lines between Manchester and Liverpool to connect the West Coast Main Line north of Wigan. It was scrapped by Shapps the Axe, apparently to assuage the constituents of Sir Graham Brady, chair of the 1922 Committee.

There remained the prospect that travellers from Edinburgh and Glasgow to Birmingham and London would at least get faster journeys south of Manchester – plus the prospect of more trains. Forget it: the overstretched East and West Coast Main Lines will continue to take the strain until, presumably, mid-century.

Anyone who believes that Labour has a good chance of winning the next general election was, two weeks ago, reassured that the calamitous project mismanagement and threatened cuts by the present government would be swiftly reversed.

On 18 September, Nick Thomas-Symonds, a minister in the shadow cabinet, assured BBC Radio 4’s PM programme: “We will build HS2 in full, and we will build Northern Powerhouse Rail in full. That’s the clear pledge that we’ve given.”

Everyone I know in rail breathed a sigh of relief. The material social and economic benefits of HS2 will be realised only by completing the project.

Evan Davis, the presenter, interjected, saying: “Just to be clear, when you say ‘in full’ do you mean to Manchester, or do you mean to Leeds as well as Manchester – that was the original vision?”

Mr Thomas-Symonds replied: “It’s both to Manchester and indeed the eastern leg that you have referred to, to Leeds, but also Northern Powerhouse Rail across from Liverpool to Leeds – indeed, the new line through Bradford.”

Six days later, though, Labour watered down the promise. Darren Jones, the new shadow chief secretary to the Treasury, said: “The Labour Party would love to see HS2 built, including the branch to Leeds. We’ve long said that.”

But he said that no commitment could be made until “proper” information had been made available by the government.

Surely there will be one cohort of winners from this world-beating example of how not to run a giant infrastructure project: travellers between Birmingham and London? Yet they comprise the one group of intercity rail passengers who currently enjoy a well-served, highly competitive market.

Avanti West Coast and West Midlands Trains compete on the West Coast Main Line between Birmingham New Street and London Euston. In addition, Chiltern Railways has – through long-term vision and investment – transformed the line between London Marylebone and Birmingham Moor Street into a viable and valuable intercity link.

Rivalry is so intense that seven trains an hour depart each way between the two cities. The very last people who need a high-speed link between Birmingham and London are, ironically, people who travel between Birmingham and London.

The very last thing the nation needs is a standalone link between these two cities. Such is our national disgrace, for which the current generation of politicians deserve a lifetime of scorn.