A few minutes after midnight on Oct. 13, 1998, I watched a man being put to death.

I remember the waiting — the endless waiting. Then the open-air walk in the chill of night from the waiting room to the watching room. The final fluttering of his eyelids.

I’d struggled with the idea of seeing Jeremy Sagastegui die. In the end, I agreed to do it because if I didn’t, someone else from my newspaper, the Tri-City Herald in Kennewick, Washington, would have to go in my place.

This is how that story began: “His lips often spread in a taunting, toothy smile. And his words often mocked the keen pain of his victims’ families. But in the black hours of Tuesday morning, Jeremy Sagastegui gasped and died quietly, showing no trace of his death-row bravado.”

For years — decades, actually — I’ve covered things I didn’t always want to. It’s called being a reporter.

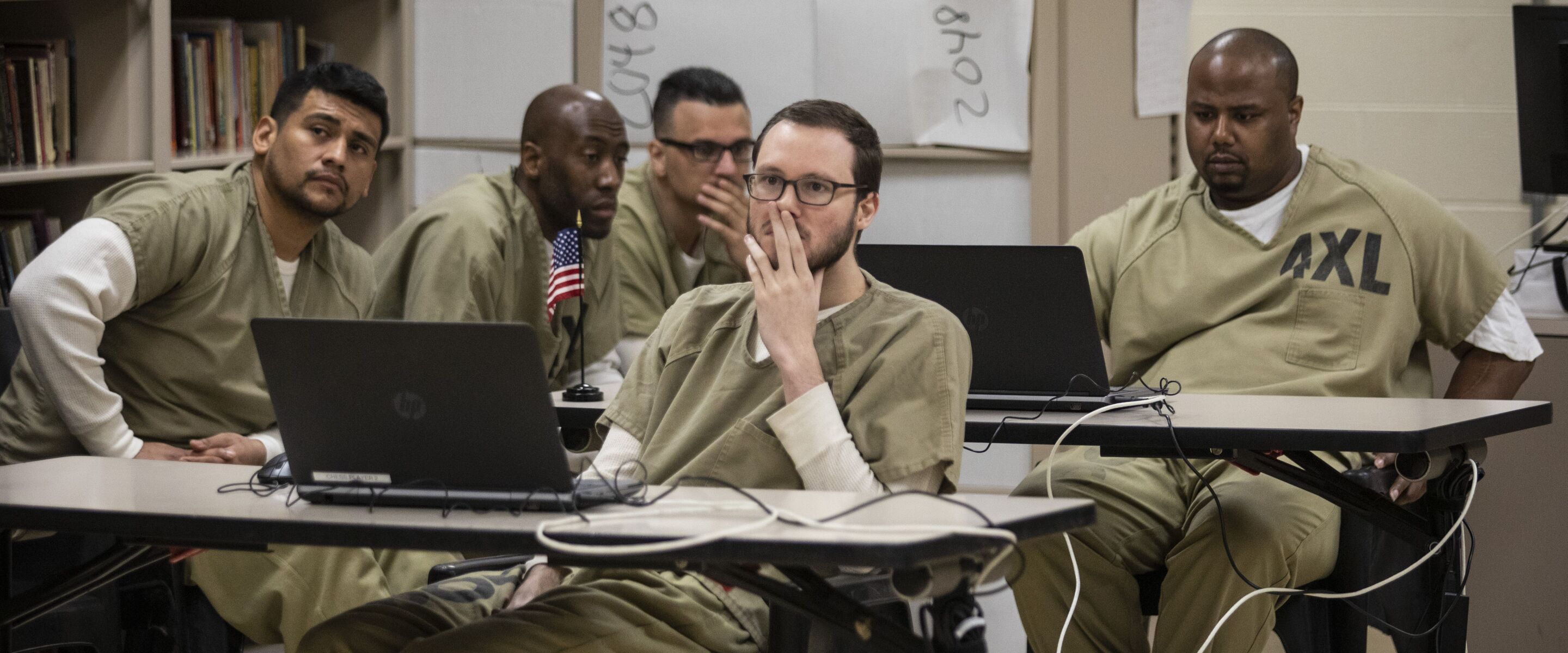

Don’t get me wrong, as a breaking news reporter I’ve had some fantastic opportunities. I’ve met everyone from Barack Obama to Oprah Winfrey to Joe Biden. Twelve years ago, I was outside Chicago’s downtown high-rise federal lockup, staring at a homemade rope dangling from a hole 17 stories up. That pre-dawn prison escape provided me with the opening chapter for a novel.

But when you cover breaking news, tragedy is always lurking — pouncing after a carelessly discarded cigarette butt or when a bus driver fails to notice an icy patch of road or when a child doesn’t drop quickly enough at the sound of gunfire.

One of my first assignments at the Chicago Sun-Times was writing eight mini-obituaries on deadline for a group of women killed in a tour bus crash in McHenry County. Every time I called a relative and got a ring, I felt a gnawing dread that the person about to answer the call might not have heard about the crash.

Reporters manage this sort of thing with gallows humor. I sometimes joke that I wish I could have a garage sale inside my head to get rid of the grim clutter.

The truth is, a lot of it becomes a blur. But some things never leave you … like the story of the 7-year-old boy whose parents had his 8th birthday party weeks early because he had incurable cancer. Tears ran down my face when I walked back to my car after that assignment.

I still think about the execution — the only one I’ve had to cover. Did it change me or how I feel about the death penalty? I’ll never say.

But ... a quarter-century after that assignment, I’m happy to say I don’t cover hard news any longer. I joined the Features Department at the Sun-Times in 2023.

It’s thrilling. It’s freedom.

The other day, my colleague Mitch Dudek, who recently became the paper’s profiles writer, crafting obituaries (and stories about the living, as well), said it’s a nice change of pace not to have to cover the first day of school after the summer break.

Agreed. No parents saying, “Sorry, in a big hurry this morning. Not interested.” No security guards barking at me to get off school property.

Instead, a few weeks ago, in the warmth of the Civic Opera House, I slipped into a stretchy blue shirt twinkling with tiny lights — for a story about a new way for the deaf to experience music. Suddenly, the curtain rose on three dozen or so stout sailors belting out the opening chorus from Wagner’s “The Flying Dutchman.”

For another story, I was at Spacca Napoli on the North Side, recently voted one of the best pizzerias on the planet, sampling the food. The server brought my 11-year-old son and me the wrong pizzas. She was mortified, apologizing endlessly, and then brought us the correct order. How dreadful — somehow we were going to have to eat leftover pizza all week!

For another assignment, I made spaghetti Bolognese in my kitchen, and Brian Ernst, the Sun-Times’ brilliant videographer, filmed me chatting with my 91-year-old father, calling in and offering his advice from his home in Florence, Italy.

It’s not all fresh mozzarella di bufala, cappuccini and opera glasses. I groaned when I was asked to write about the return of McDonald’s McRib. But apparently people read this stuff.

And I panicked when I went to a screening of the movie “Dumb Money” and couldn’t figure out how to take notes in the dark (a veteran later told me that he sits by the aisle, near the floor lights).

Still, it’s a heck of a lot better than standing outside the Cook County Jail for two hours in January, fingers and toes numb, waiting for someone to come out — and knowing, with near 100% certainty, that he won’t answer your questions no matter how loudly you shout at them.

So the next time you see someone in front of your kid’s elementary school or the State Street Macy’s during the Black Friday sales, with a hopeful smile and bouncing on his heels in the freezing cold with notebook and pen in hand, he probably urgently needs to go to the bathroom — but first, he needs a quote from you.