Terms such as ‘altered’ and ‘extended’ chords are relatively simple to explain. Extended chords add other notes from the scale to the existing root-3rd-5th triad (for example, C-E-G), so if we add a 7th, we’d call this a major 7th chord (C-E-G-B).

We can extend up to a 13th in this way by progressively adding in the non-chord tones of a scale – in theory, at least.

In practice, root-3rd-5th-7th-9th-11th-13th played simultaneously makes for a dense, almost dissonant voicing.

On guitar we’d struggle because we only have six strings, plus a limited reach and number of fingers! So we tend to omit non-essential notes. The 5th is often the first to go, then the 11th gets the chop in 13th chords for clarity.

Altered chords contain non-diatonic notes – that is, notes that have been raised or lowered from their usual place in the scale. The examples below provide further explanation!

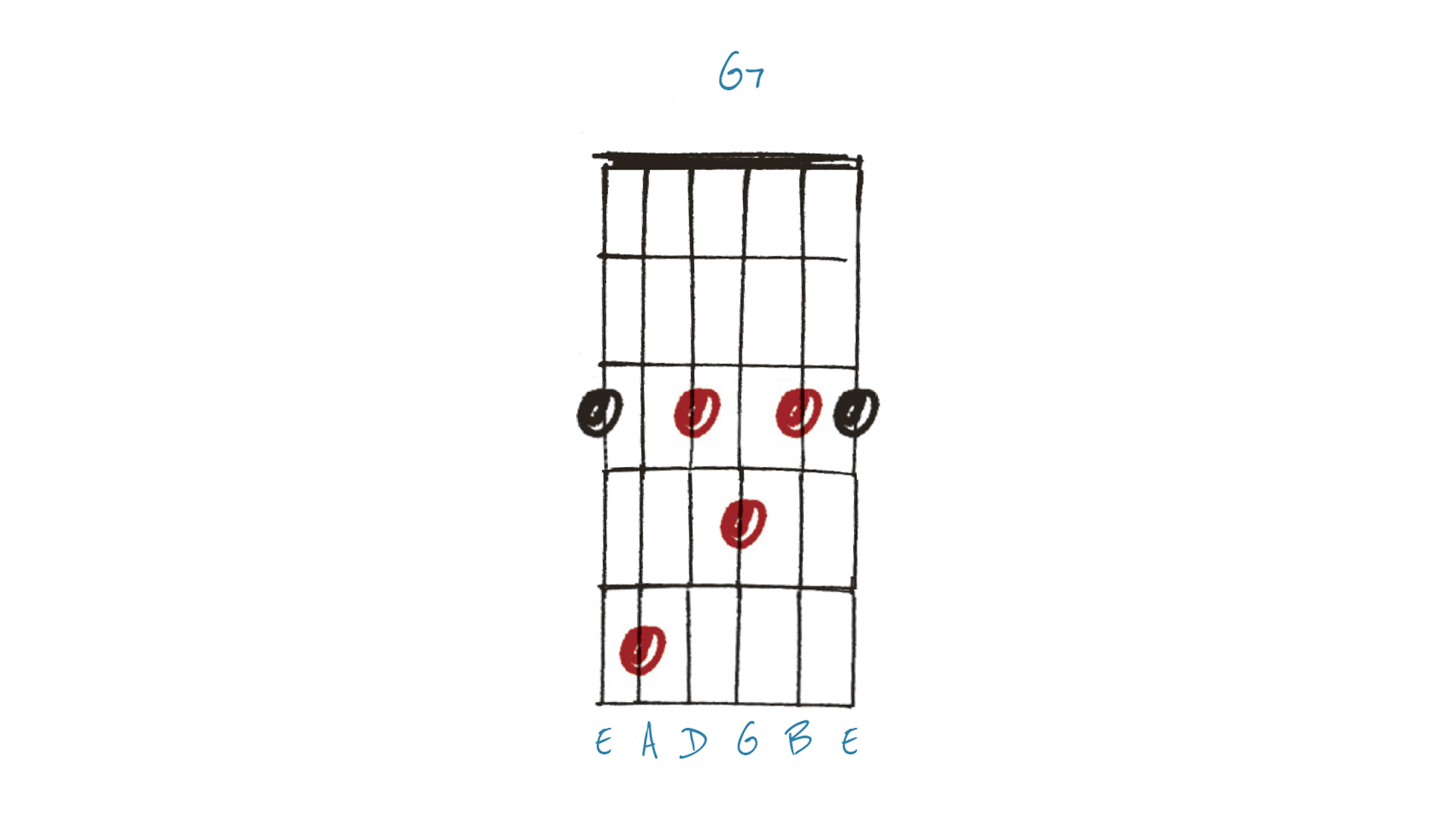

Example 1. G7

As a reference point, here is a G7 chord. These contain a b7th, which is referred to as the dominant 7th (and not considered as ‘altered’ in the theoretical sense). From low to high, we have G-D-F-B-D-G. Two roots (G), one 3rd (B) one dominant 7th (F) and two 5ths (D). Try not to let the non-linear nature of the guitar distract you from music theory’s basic principles.

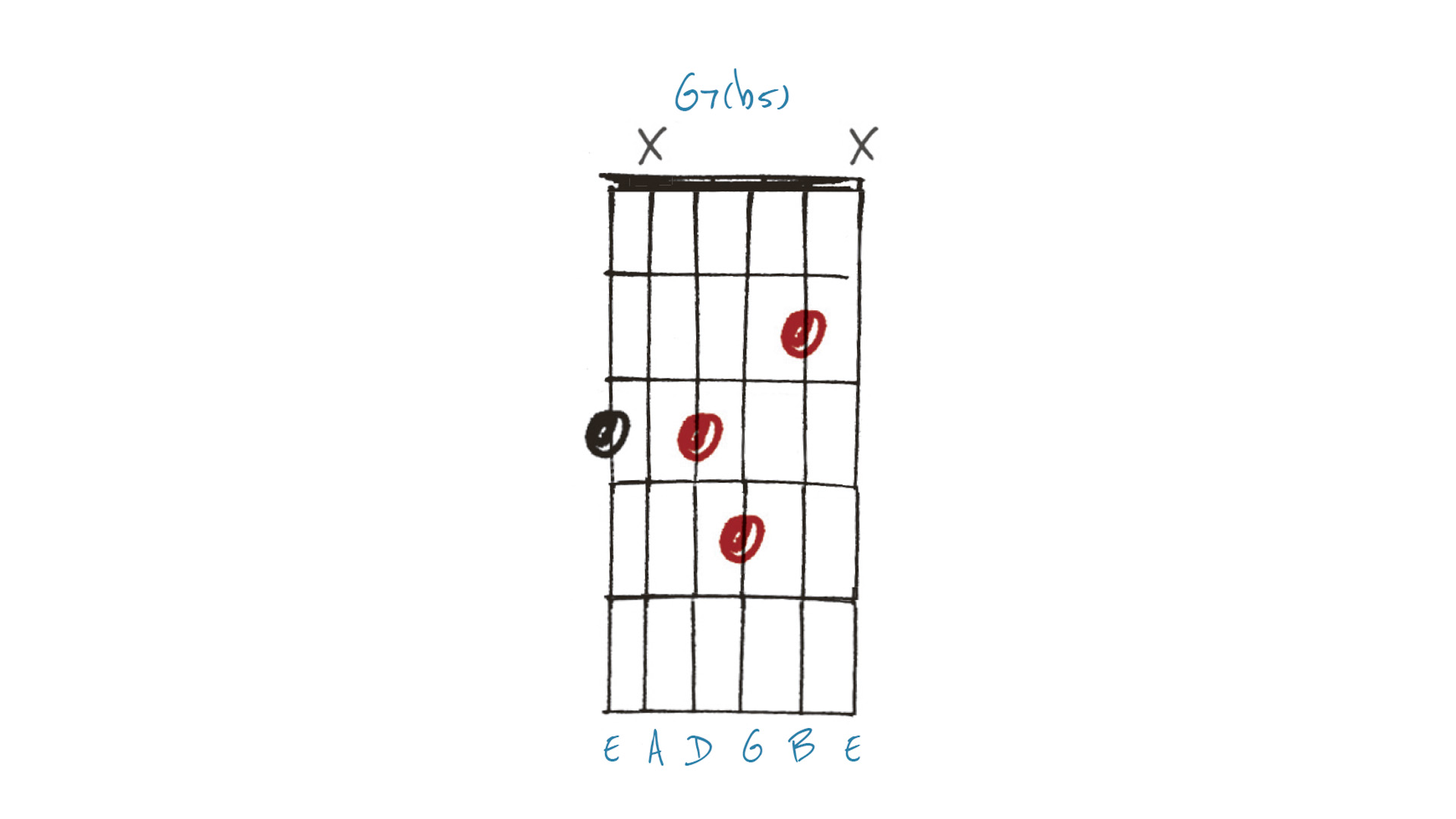

Example 2. G7(b5)

An altered version of the G7 in Example 1 could be this, a G7(b5). Let’s talk it through from low to high: the root (G) is at the bottom, followed by the muted fifth string, coincidentally where the 5th (D) would also appear. Next, we have the b7th (F) and the major 3rd (B). All fairly standard apart from the omitted 5th. The b5th (Db) is where the alteration happens, on the second string.

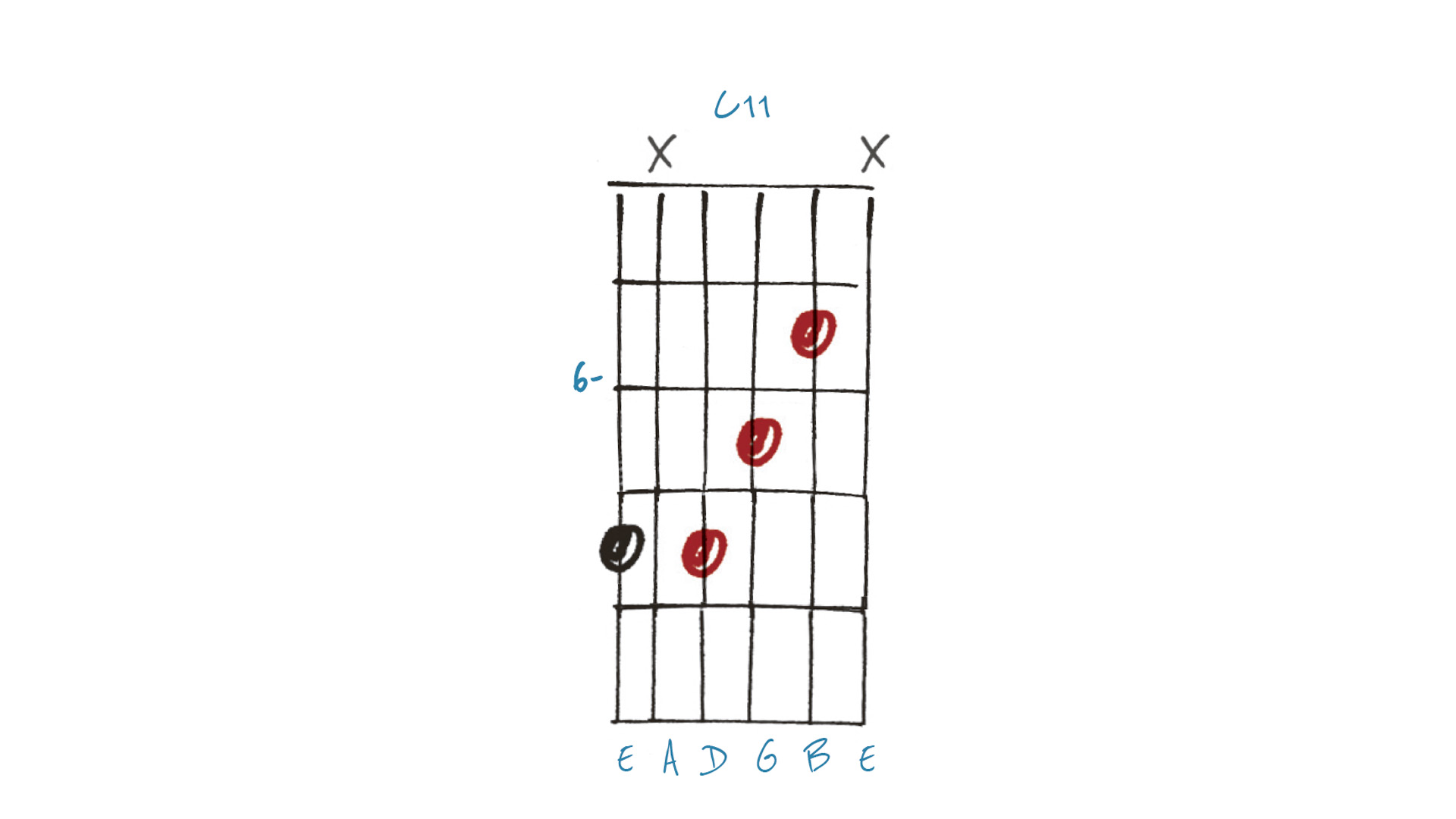

Example 3. C11

Taking another chord as a reference, here’s a C11. From low to high, we have: Root (C) - dominant 7th (Bb) - 9th (D) - 11th (F). Again, the 5th is omitted, which helps with fingering on the guitar, but it’s also common practice to stop chords becoming too harmonically dense and hard for our brains to decipher!

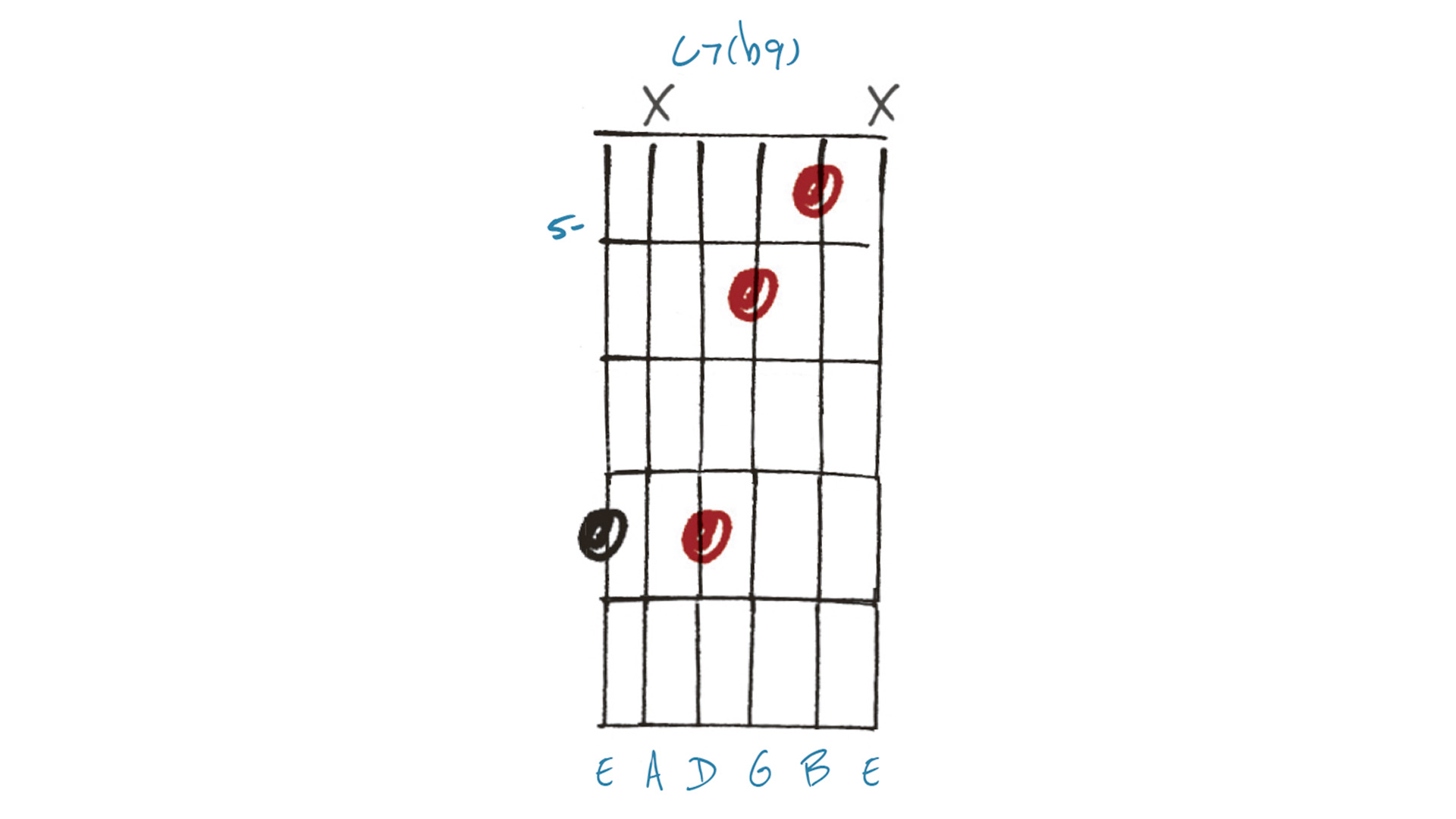

Example 4. C7(b9)

An altered version of the C11 in Example 3 could be this, a C7(b9). We’ve lost our 11th (F) by shifting it down to an E at the 5th fret of the second string. This becomes the major 3rd, so there’s no need to name it separately. However, we do have a Db on the third string, a semitone below the 9th from the previous C11 chord. This is our altered note.

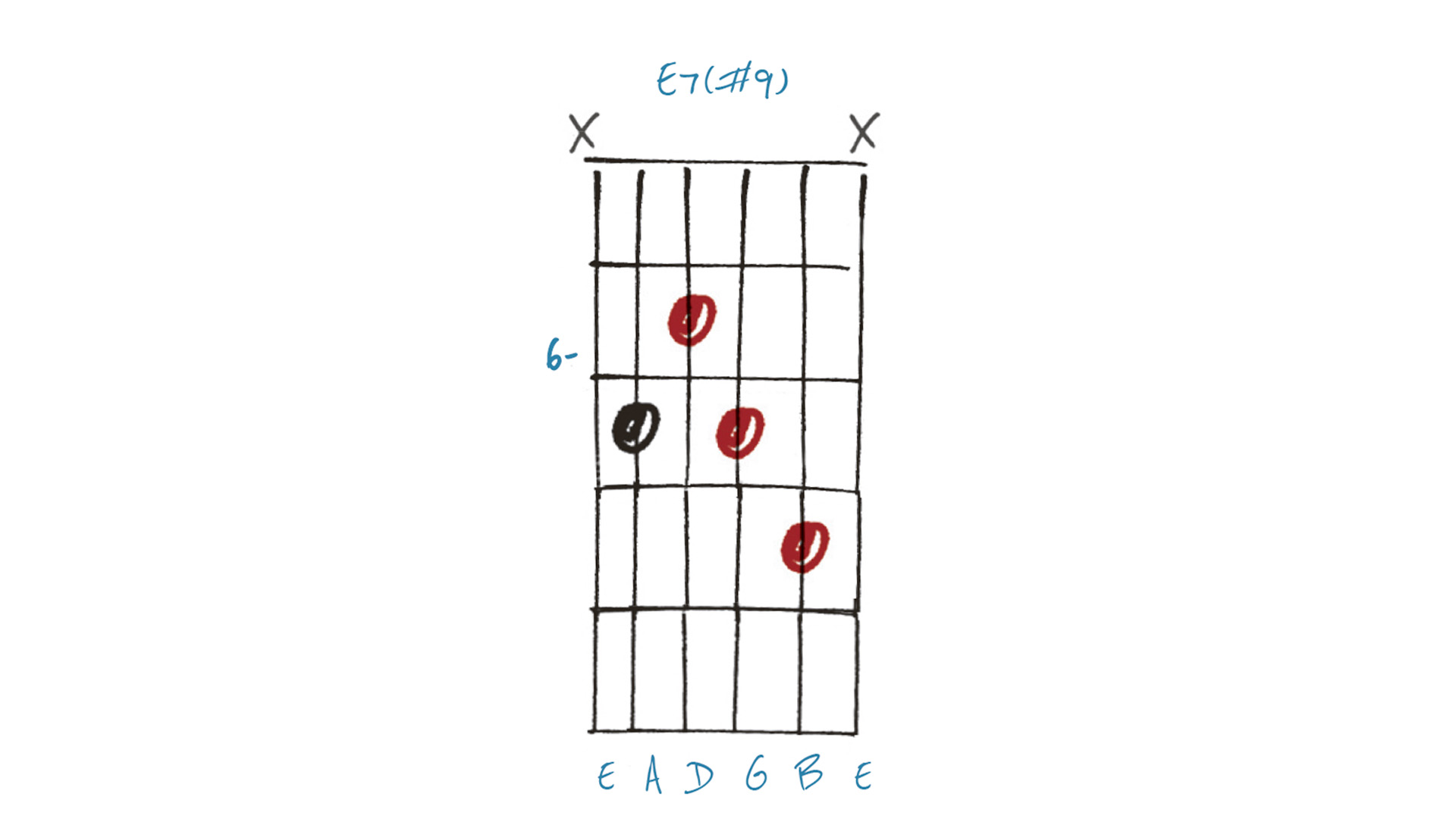

Example 5. E7(#9)

The E7(#9) is a very well-known chord, but it’s interesting to look at it from this perspective. If we take it from low to high, we see: root (E) - major 3rd (G#) -

dominant 7th (D) - #9th (G). If you take that G at the top down to F#, we’re looking at a regular E9 chord.