High and often hidden transaction fees on migrant money going to family overseas are hitting the world's poor, according to development economists. Now a fintech operating in NZ is calling for bank remittances to be included in the Commerce Commission banking market study.

Global currency tech company Wise is calling on the Commerce Commission to investigate what banks charge for overseas remittances when it conducts its market study into the retail banking sector.

International research over the past decade, including from the International Monetary Fund and Australia’s Productivity Commission, has found “stubbornly” high transaction costs for international payments and a lack of transparency around fees and charges.

And New Zealand is no different, says Jack Pinczewski, Asia-Pacific government relations manager for UK-based foreign exchange fintech Wise.

As well as the fixed fees for international payments, people sending money back to family overseas are hit with hidden costs around the exchange rate, he says, particularly if they use banks. The person sending the money may be handing over $1000, say, but by the time the money reaches its destination, it could be worth the equivalent of $950 or even $900.

And that lost 5-10 percent over time can make a huge difference to someone's struggling family overseas.

“A Commerce Commission inquiry is an important starting point to look at the problem in New Zealand,” Pinczewski says. “We had a discussion with commission officials when they came to Australia last year, and I’m satisfied to think our feedback potentially went into the development of this market study. We’d asked them to do something specifically for international money transfers.

“We’re encouraged that the New Zealand government is responding to industry concern about lack of competition, and we will be calling on the Commerce Commission to look at international payments as a necessary part of this market study.”

"A major stumbling block in sending money home is the high, some would argue excessive, transaction costs involved” – International Monetary Fund study, 2022

The commission’s announcement of its 14-month-long inquiry into “whether competition for personal banking services in New Zealand is working well and, if not, what can be done to improve it” doesn’t specifically refer to remittances. However, its first step is talking to stakeholders to find out which issues people think need to be part of the investigation.

“International transfer services are within the broad scope of personal banking services,” commission spokesperson Charlotte Rosier told Newsroom. “The commission will consult on the focus areas for the study through a preliminary issues paper, which provides an opportunity to present views, reasons and supporting information.”

That paper is due next month, with the final report expected August 2024.

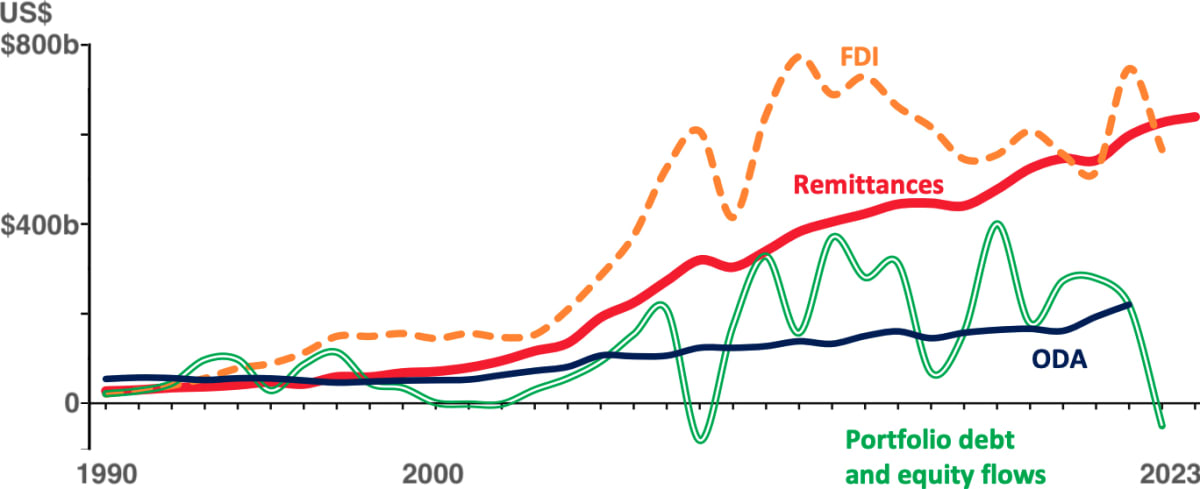

“Remittances matter” according to an IMF working paper released in November last year. Family sending money home is a crucial source of funding for developing countries, and they are increasing every year.

Estimates of the total amount sent back by migrants to their families worldwide vary, but the 2022 IMF study put it at $US550 billion in 2021. Over half went to people in rural areas, the IMF said, and about 75 percent is used to cover basics like food, medicines and school expenses.

“Developing countries are looking at avenues to encourage remittance flows to grow even further. However, a major stumbling block in sending money home is the high, some would argue excessive, transaction costs involved,” the IMF authors found.

“Considering fees, exchange rate margins and other costs, between 5 and 15 percent of remittances are ‘lost’.”

An earlier study in the Journal of Development Economics found high transaction costs actually put people off sending money home.

One of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals is reducing the transaction costs associated with remittances worldwide to no more than 3 percent. Achieving that goal would mean an extra $US20 billion getting into the hands of families rather than being used to boost the profits of the banks and other international payments organisations.

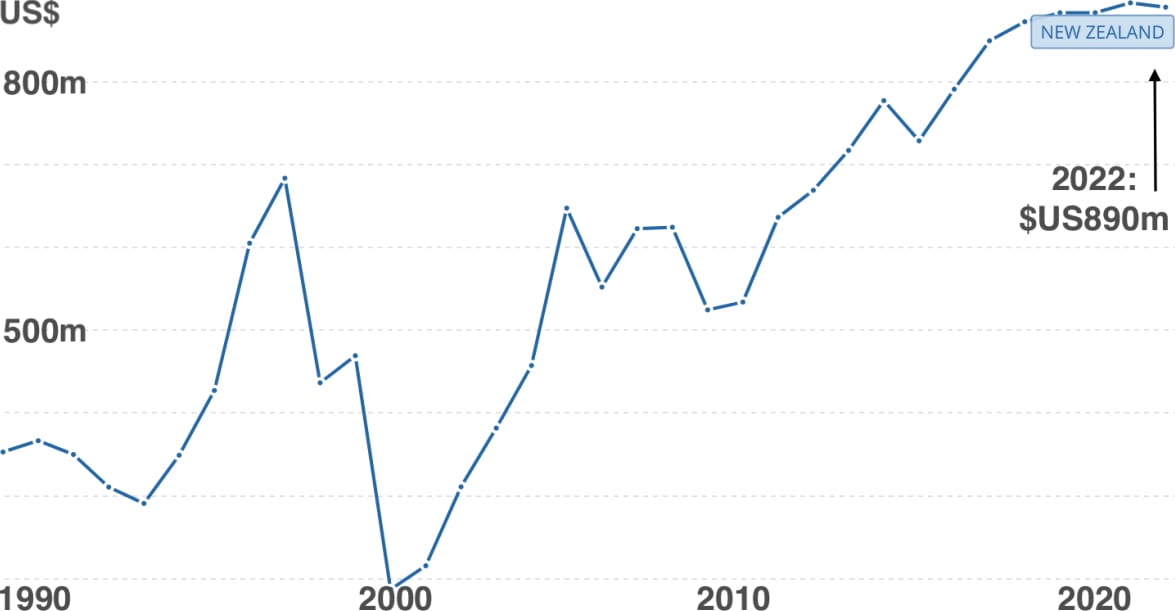

The World Bank puts out remittance estimates based on IMF balance of payments data. According to those figures, people living in New Zealand sent $US890m ($NZ1.4b) overseas in 2022.

Exactly where the money is going isn’t clear, but a lot of it will end up in the Pacific, where remittances are “a significant source of household income, especially in Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu and Fiji,” according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

“In recent years, remittances to the Pacific (including RSE [recognised seasonal employer scheme] workers’ remittances) have been worth around NZ$852 million each year, with around 30 percent coming from New Zealand (30 percent from Australia, 30 percent from the US, and 10 percent from elsewhere).”

Pinczewski, who is based in Australia, says numbers from Canberra suggest individual migrants working minimum wage jobs can be sending 40 percent of their earnings to family.

He thinks New Zealand figures could be similar.

“Say you are earning the equivalent of $50,000 in a given year, if you are sending 40 percent back home, that’s $20,000. If the fee is 10 percent, which it can be in some circumstances, that’s $2000.

He sends Newsroom figures from Westpac that suggest the difference between the “buy” and the “sell” rate for changing Australian dollars to New Zealand dollars is 5 percent, but says it can be more with other currencies.

In addition, most banks charge an additional fixed transaction fee.

That fixed fee doesn’t worry Pinczewski in terms of competition in the market – the focus of the Commerce Commission investigation. What frustrates Wise, as a new-ish entrant to the international payment market, is that the exchange rate margin costs are hidden when it comes to the banks.

Unless customers know what the exchange rate should be, and do the maths between what they send from New Zealand and what arrives with their overseas family, they have no way of knowing what cut the bank is taking. And because it’s hard to compare the transaction costs between different players, people often default to the system they know, which is often their own bank.

Pinczewski says Wise’s average fee is 0.66 percent, although it varies depending on the market and the amount of money being transferred.

Consumer protection and advocacy group Consumer NZ has long been worried about high transaction costs for international bank transfers, though it hasn’t specifically looked at remittances. Its most recent investigation (paywalled) was in 2019, when it looked at the cost of moving $100 to the UK using five banks and five online online money transfer services.

“If you go with the banks, sending and receiving fees and stingy exchange rates can leave your payment shrunk on arrival,” Consumer found.

Depending on where a customer went, their $100 could turn into £53 (Wise) or £52.50-£52.60 (three of the other online transfer services). ANZ and Kiwibank worked out at £52, but Westpac, which offered “the stingiest exchange rate”, turned $100 into £39.73. Westpac told Consumer at the time this was an error.

Of course things may have changed since 2019.

When Newsroom asked about the Commerce Commission inquiry, Consumer NZ chief executive Jon Duffy agreed there needs to be greater bank fee transparency, including around remittances, but wasn’t sure the market study was the right vehicle.

“We’d be keen to see Commerce Commission do more work around sneaky fees under the Fair Trading Act, but don’t agree that the topic should form part of the market study into banking, which is already covering a lot of ground and needs to stay focused on the retail banks.”

NZ Banking Association chief executive Roger Beaumont says banks will cooperate with the study whatever it involves.

“The Commerce Commission will determine the scope of the market study. Banks are open and transparent and will participate fully in the areas the Commission wishes to look at.”