The color of Earth's oceans has changed significantly over the past two decades, and these shifts are the result of human-driven climate change. They cannot be explained by natural variability alone and have affected over 56 percent of our planet's oceans, an expanse larger than the total area of land on our planet.

The color of Earth's oceans are a reflection of the organisms and minerals that lie within its waters. This means, though these color variations may appear subtle to the human eye, they undoubtedly indicate that marine ecosystems are in flux. Although what specific changes are occurring in these ecosystems aren't totally clear as of yet, the team behind the findings is certain human activity and its effects on climate are the cause.

"I've been running simulations that have been telling me for years that these changes in ocean color are going to happen," Stephanie Dutkiewicz, study co-author and senior research scientist from Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and the Center for Global Change Science, said in a statement. "To actually see it happening for real is not surprising, but frightening. And these changes are consistent with man-induced changes to our climate."

Related: Space station data show how dust contributes to climate change

How does the ocean get its color?

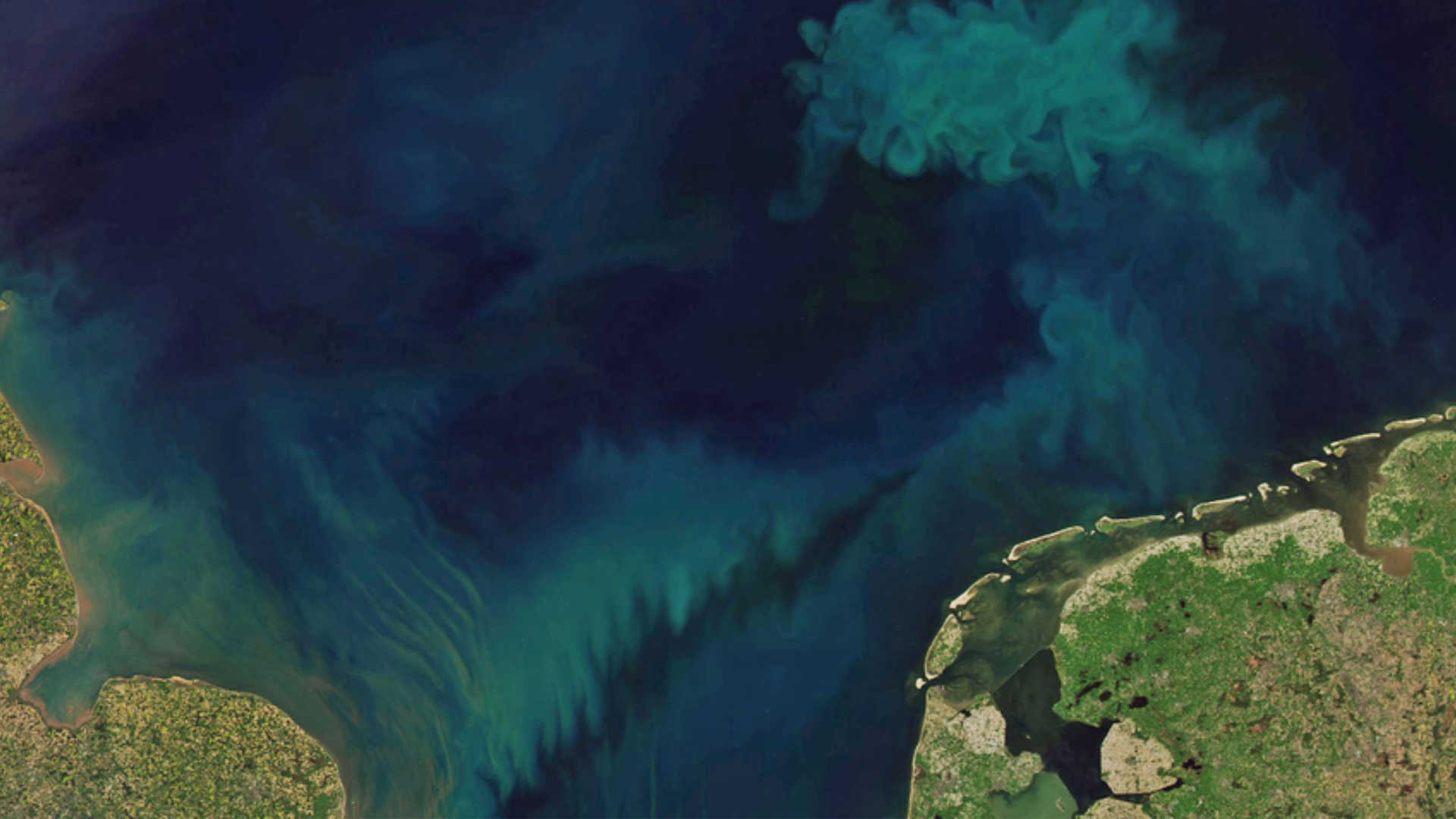

The color of the ocean can be used as a gauge to assess what dwells in its upper layers. Deep blue waters, for instance, indicate an absence of life while green waters indicate the presence of plant-like microbes called phytoplankton that contain the green pigment chlorophyll.

Phytoplankton harvest sunlight and use carbon dioxide to create sugars via photosynthesis, thus forming the foundation of the oceanic food web. They're fed on by small creatures, like krill, which feed larger fish, which in turn feed seabirds and marine mammals.

Beyond feeding the oceans, this process of photosynthesis also means phytoplankton are vital in capturing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Because carbon dioxide is a major greenhouse gas, scientists keenly monitor phytoplankton across ocean surfaces to see how colonies of this microorganism respond to climate change.

This is traditionally done by monitoring that green pigment, chlorophyll, which helps phytoplankton and plants harvest sunlight. Changes in chlorophyll can be seen in the ratio of blue versus green light reflected on the ocean surface, a balance that can be tracked with spaceborne satellites.

However, determining a climate change-driven trend solely through changes in chlorophyll would take some 30 years, experts say. So in 2019, scientists determined that by tracking smaller variations of other ocean colors as well they could cut a chunk of time off that figure to spot signals of climate change with just 20 years of monitoring.

"I thought, doesn't it make sense to look for a trend in all these other colors, rather than in chlorophyll alone?" B.B. Cael, lead author of the research and National Oceanography Center scientist, said. "It's worth looking at the whole spectrum rather than just trying to estimate one number from bits of the spectrum.

"This gives additional evidence of how human activities are affecting life on Earth over a huge spatial extent."

Viewing ocean color from space

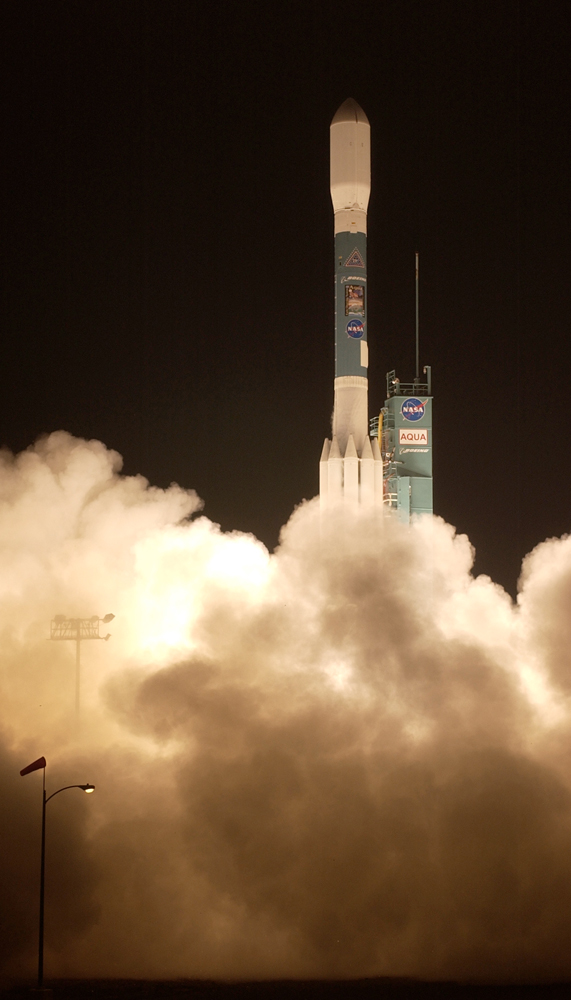

To reach their current findings, Cael and fellow researchers analyzed ocean color measurements collected by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Aqua satellite.

For 21 years, MODIS has observed the oceans in seven wavelengths of light, including two wavelengths used to track chlorophyll in particular. The instrument sees the ocean as a mix of subtle wavelengths, from blue to green and even red, in contrast with the isolated azure hue our eyes have evolved to see. This means it can spot changes way too subtle to be seen by human vision alone.

Cael assessed the seven oceanic colors measured by MODIS between 2002 and 2022, observing how they shifted in individual regions during each year to get an idea of natural variation.

Zooming out on this year-by-year data then allowed the researcher to see how changes progressed over a total 20 years. This revealed to Cael a clear trend that wasn't present in simply annual variability. To determine if the trend was the result of climate change, Cael compared it to two ocean-color models. One considers the addition of greenhouse gases and the other does not.

Ultimately, the satellite data conformed to the greenhouse gas model's prediction of a 20-year trend in changes to ocean color in around half of the world's surface oceans. This showed the trend observed in MODIS was more than a random variation, and suggested a new as well as faster way to detect climate change-driven changes to marine ecosystems.

"The color of the oceans has changed, and we can't say how. But we can say that changes in color reflect changes in plankton communities that will impact everything that feeds on plankton," Dutkiewicz said. "It will also change how much the ocean will take up carbon because different types of plankton have different abilities to do that.

"So, we hope people take this seriously. It's not only models that are predicting these changes will happen. We can now see it happening, and the ocean is changing."

The team's research was published this month in the journal Nature.