The next time you need to take antibiotics, they may not work. So you may be prescribed a different antibiotic, which also may not work. Maybe nothing works.

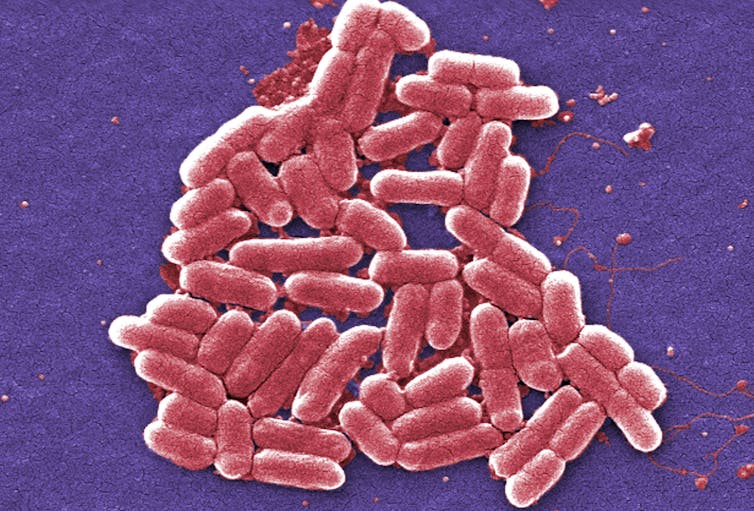

This is what happens when bacteria develop resistance to drugs designed to kill them, putting modern medicine at risk, and making everyday infections deadly.

Climate change is accelerating the emergence and spread of these “superbugs”, which thrive in warm, wet conditions.

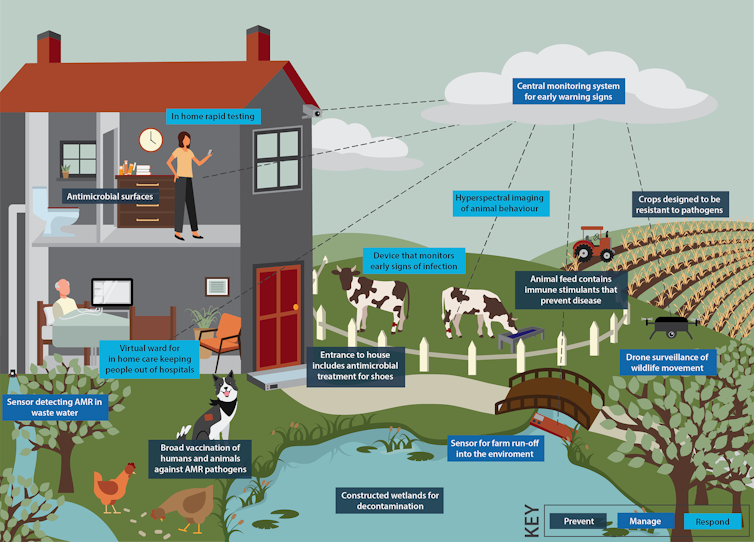

Our new report, released today, calls for modern solutions to these challenges. These include integrated surveillance and sensing systems, point-of-care diagnostics, new vaccines, and “prevention through design” of better farms, hospitals and other high-risk settings.

Overuse and abuse

Antimicrobials are medicines used to prevent and treat infections in humans, animals and plants caused by microbes. There are four main types:

antibiotics treat infections caused by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus (staph or golden staph) and Group A streptococcus (which causes strep throat)

antivirals treat infections caused by viruses such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID)

antifungals treat infections caused by fungi such as tinea and thrush

antiparasitics treat infections caused by parasites such as Giardia and Toxoplasma.

Overuse and misuse of antimicrobials in both human and animal medicine is driving the evolution of drug-resistant strains of disease-causing microbes.

The World Health Organization has declared antimicrobial resistance one of the top ten global public health threats.

It is currently estimated to directly cause more than 1.25 million deaths worldwide each year, costing billions of dollars. Each year the problem escalates.

We must act now before widespread antimicrobial resistance manifests in total treatment failure.

A climate for superbugs

Higher temperatures have been found to promote the growth, infection and spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, both in humans and animals.

Flooding from extreme weather events overloads sanitation infrastructure, increases congestion in already-crowded regions, and propagates antibiotic resistance through the flow and overflow of sewage – a proven reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes.

An increase in rainfall will also result in increased runoff from farms and industry and, consequently, result in higher levels of pollutants in the water.

Environmental pollutants have been shown to promote the production of antibiotic resistance genes and increase bacterial mutations that can exacerbate resistance.

Increased nutrient-rich agricultural runoff will enhance the likelihood of algal blooms in water systems, and high bacterial concentrations will boost opportunities for the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes.

Droughts present problems too, as water scarcity leads to reduced sanitation and results in higher densities of people sharing the same water source or using contaminated water for agricultural purposes.

Crowding and sharing water can increase the likelihood of waterborne diseases becoming epidemics, as common symptoms such as diarrhoea and vomiting cause further reductions in hygiene and increase contamination of water.

Malnutrition, overcrowding and inadequate sanitation all increase the risk of children contracting antibiotic-resistant gut infections. This will inevitably result in more severe diarrhoea; a point of concern if antibiotic resistance increases as it would prevent current medications from being effective.

The shared environment for humans and animals is increasingly overlapping as the global population grows. This increases the likelihood of pathogen transmission and resistance between the environment, humans and animals. If climate change is not addressed, it will have a disproportionate impact on the health and wellbeing of people, especially in low- and middle-income countries around the world.

Read more: Scientists around the world are already fighting the next pandemic

Developing new drugs is not the only solution

It’s not as simple as making new drugs to replace failing ones.

Discovering new antibiotics is a slow and expensive process. They have a high failure rate, and most do not progress to the human clinical trial stage.

New antimicrobial drugs are prescribed sparingly to minimise the likelihood of antimicrobial resistance. This results in lower demand, fewer sales and no return on the millions of dollars of investment.

While this is crucial, we require a more holistic antimicrobial resistance approach that includes protecting the efficacy and availability of the medicines we currently have, and finding innovative solutions that we can start to deploy as soon as possible.

Our Mission: to fight superbugs

While Australia has been taking decisive action to reduce antibiotic use and discover alternatives, the nation’s prescription rate remains high relative to other similar developed countries.

Recognising the urgency, CSIRO, the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, and the Department of Health and Aged Care, co-developed the Minimising Antimicrobial Resistance Mission.

Our mission aims to prevent, manage and respond to antimicrobial resistance using new and emerging technology.

To explore the types of technologies that could be used to tackle antimicrobial resistance, CSIRO worked with the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. The resulting report provides insights into how we best prompt collaboration, validate policy and explore potential actions and innovative solutions to mitigate antimicrobial resistance.

Following an initial exploratory survey in March 2022, the team conducted a series of roundtable conversations and expert interviews, alongside desktop research.

Consultations involved more than 100 stakeholders spanning government, academia, and industry. Key technologies that could be used to reduce the prevalence and spread of antimicrobial resistance were identified.

Consultations also explored the barriers to implementation of the technology-based solutions, and key enablers.

The message from stakeholders was clear – there is a lack of coordination in the efforts against the rise of antimicrobial resistance, significant data silos across states and sectors, and a need to increase community understanding about antimicrobial resistance.

A need to streamline and simplify pathways to market was also called out as a key requirement to enable technology-based solutions to get to the places they are needed the most – both within healthcare settings, and beyond.

Two key recommendations emerged from the report:

Establish centralised coordination and leadership for antimicrobial resistance management to align and coordinate domestic and international activities across human health, animal health and environmental health sectors.

Streamline and optimise the commercialisation process to support Australian antimicrobial resistance solutions entering the market.

Imagine the world in 2050

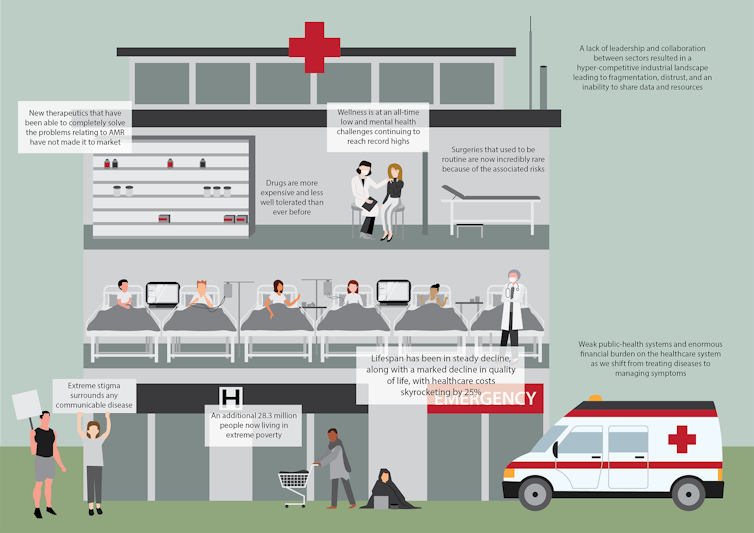

Without preventative action, it is estimated that by 2050 antimicrobial resistance would lead to 10 million people dying every year and cost the global economy US$100 trillion.

We have a critical window of opportunity to act now, to avoid going back to a time when simple infections were deadly and surgeries were too risky to perform.

Prevention strategies such as vaccination and the use of sensing to know when and where to deploy resources will be essential.

We hope our report will inspire governments to invest in tackling antimicrobial resistance in a coordinated and cohesive manner before we sleepwalk into a superbug’s paradise.

Branwen Morgan receives funding from CSIRO.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.