Arizona’s clemency board has unanimously declined to recommend to Gov. Doug Ducey that the death sentence of a prisoner be delayed or reduced to life in prison in what would be the state's first use of the death penalty in nearly eight years.

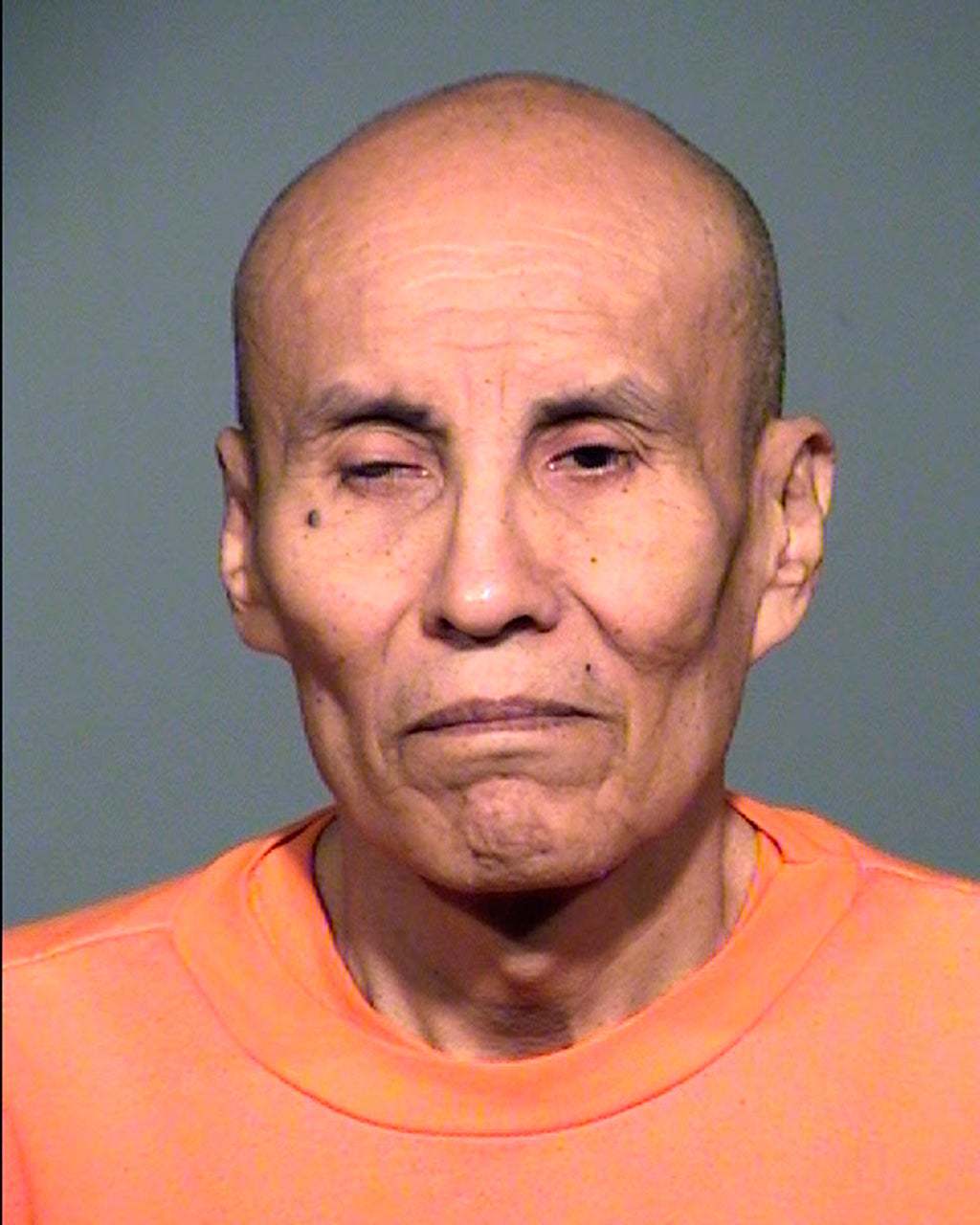

The decision by the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency on Thursday marks one of the last steps before Clarence Dixon’s execution in the 1978 killing of Arizona State University student Deana Bowdoin. The execution is scheduled for May 11.

The board made the decision after hearing tearful comments from Bowdin’s sister, Leslie Bowdin James, who reflected on the brutality her 21-year-old sister suffered.

“There is not one legal, social or moral imperative for recommending a reprieve or commutation,” she said.

The board’s decision keeps the execution on track, at least for now.

A hearing is scheduled Tuesday in a Pinal County court to consider whether Dixon is mentally fit to be executed. His lawyers argue Dixon’s psychological problems keep him from rationally understanding why the state wants to end his life. Prosecutors have said in court records that the hearing will likely lead to a delay in the execution.

Authorities say Bowdoin, who was found dead in her apartment, had been raped, stabbed and strangled with a belt. Dixon had been charged with raping Bowdoin, but the charge was later dropped on statute-of-limitation grounds. He was convicted, though, in her death.

Before his conviction in Bowdoin’s death, Dixon was serving life sentences for sexual assault and other convictions stemming from an attack in the mid-1980s on a 21-year-old Northern Arizona University student. DNA samples taken while he was in prison later linked him to Bowdoin’s killing, which at that point had been unsolved.

In arguing that their client is mentally unfit to be executed, Dixon’s lawyers say he erroneously believes he will be executed because police at Northern Arizona University wrongfully arrested him in the previous case.

His attorneys concede he was in fact lawfully arrested then by Flagstaff police and said he can’t distinguish between reality and fantasy in the case involving the NAU student.

Board chairwoman Mina Mendez said Bowdin suffered before her death as a result of Dixon’s actions, that the victim’s family is haunted by the killing and that she believes the condemned man understands why he will be executed, despite claims that he is mentally unfit.

“What was missing was remorse or any kind of acceptance of responsibility,” Mendez said.

Board member Michael Johnson said, “I don’t see him having received any injustice.”

Dixon chose not to be present at the hearing.

His lawyers had tried unsuccessfully to get the courts to call off the hearing, arguing the board’s makeup violated a law that lets only two people from the “same professional discipline” serve on the board. Three board members worked previously in law enforcement.

Despite their objections, Dixon’s attorneys still participated in the hearing.

Amanda Bass, one of Dixon’s lawyers, said the defense team wasn’t disputing whether their client was guilty of murder or minimizing the suffering of Bowdoin’s family, but rather were asking for mercy because key information about his mental illness wasn’t heard at his trial, where Dixon had represented himself after firing his attorney.

Bass said jurors didn’t hear that Dixon had been diagnosed with schizophrenia as a young man and at one time had been committed to the Arizona State Hospital.

Bass also said Dixon was the subject of a civil commitment order issued two days before Bowdoin’s killing by then-Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor after the future U.S. Supreme Court justice had found Dixon “not guilty by reason of insanity” in a 1977 assault case. The order was issued two days before Bowdin's killing.

“The jury didn’t know any of this,” Bass said.

Ellen Dahl, a Maricopa County prosecutor, said the cruelty suffered by Bowdin was unimaginable.

“Mercy?” Dahl asked. “Where was the mercy for Deana as she lay with a strap across her neck?”

The last time Arizona used the death penalty was in July 2014, when Joseph Wood was given 15 doses of a two-drug combination over two hours in an execution that his lawyers said was botched. Arizona has 112 prisoners on death row.

States, including Arizona, have struggled to buy execution drugs in recent years after U.S. and European pharmaceutical companies began blocking the use of their products in lethal injections. Last year, Arizona corrections officials revealed that they had finally obtained a lethal injection drug and were ready to resume executions.

Arizona has 113 prisoners on death row.