THOMAS Skottowe has always been a shadow on the pages of Hunter early convict history.

Until now, relatively little has been known about Skottowe, the commandant of the Newcastle penal settlement from 1811 to 1814.

Why is it that we know very little about him? For example, no portrait of him seems to have even survived. But surprisingly, he did leave a lasting legacy for which he should be remembered.

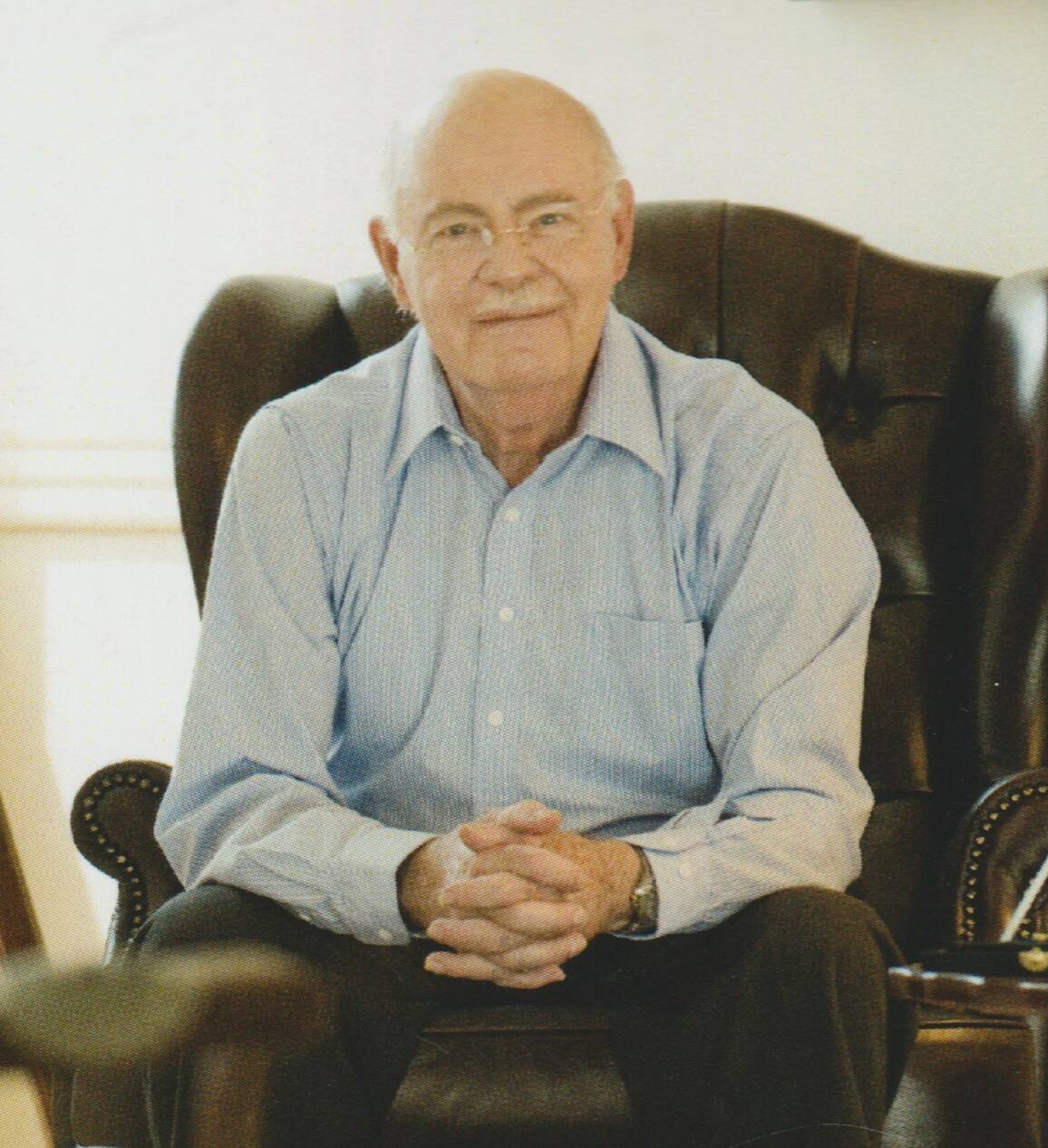

Emeritus Professor Kenneth Dutton, of Newcastle, is aiming to rectify the omissions of the past in a new publication throwing the spotlight on British Lieutenant Thomas Britiffe Skottowe of the 73rd Regiment.

According to Dutton, sufficient recognition is long overdue. Unlike some other commandants of the early Newcastle penal settlement, Thomas Skottowe has no local memorial.

Compare him, for example, with Commandant James Wallis (1816-1818), after whom Wallis Plains (Maitland) was named.

Then there's the some say notorious, possibly maligned, Major James Thomas Morisset, commandant from 1818 to 1823 after whom a Lake Macquarie township is named. He has the reputation of being a 'bogeyman' because of his disfigurement gained in war.

And Skottowe? According to Dutton, the man has a significant place in Newcastle's early history that needs to be properly explored.

To set the record straight, the retired academic has penned a beautifully bound, lavishly illustrated 80-page booklet entitled Two Short Sketches from his comprehensive research. The first of the linked family stories is entitled The Legacy of Thomas Skottowe, while the second involves what he refers to as the remarkable story of Mary Ann McCarthy, his common-law wife while in penal Newcastle.

For in many ways, Professor Dutton's detective work resembles, to me anyway, an old game called seven degrees of separation, involving actor Kevin Bacon, exploring how everyone and anyone, could theoretically be linked to one another at one time or another. Or as the academic succinctly puts it : "The story begins and ends in Newcastle". I was intrigued and had to read on.

It seems that Thomas Skottowe was a man who "in spite of his somewhat cavalier treatment of the women in his life" appears to have been one of the more humane commandants of the Newcastle prison settlement. Skottowe's humane treatment of those under his command led to two significant contributions to our early colonial history. One was a unique illustrated guide to Australia's flora and fauna, and the other was the creation of the first dictionary compiled on Australian soil. But more about this literary creation later.

One of the earliest and rarest pictures of our prison era of Newcastle comes from the pen of convict Richard Browne and is dated 1812. It shows the Hunter peninsula jutting into the wide Pacific Ocean with the most prominent feature of the sketch being a large, shark-fin like shape of an offshore island (later Nobbys).

Dutton speculates Skottowe obviously provided the convict artist with pen, ink and paper to record for posterity what he observed about him.

What further resulted was what became known as the Skottowe manuscript, an extraordinary record of the flora and fauna of the Newcastle penal era illustrated by Richard Browne. This invaluable record of select specimens of birds and animals from more than 200 years ago was eventually bequeathed in 1907 to the people of NSW as part of the Mitchell Library Collection.

A facsimile edition of the illustrated manuscript was then eventually published as a Bicentenary project in Newcastle in 1988 as a set of two volumes, including Skottowe's commentary on the local flora and fauna with a foreword by Sir David Attenborough.

Dutton first came across the manuscript from the colonial era after he became honorary librarian at the Newcastle Club in 2010 and then started to investigate the author of the work. He became fascinated also with the rags-to-riches story of his neglected common-law wife, Mary Ann McCarthy.

Now to Skottowe's other claim to fame. Amid the ranks of felons under his rule was a con man called James Hardy Vaux, better known today as 'Flash Jim'. To ingratiate himself with the authorities, starting with Thomas Skottowe, the felon set about writing a rather unique dictionary of the colony's criminal slang.

This was in 1812. The manuscript eventually found itself in London where it was published in 1819. It became a sensation, weaving together English regional dialect words, then Aboriginal words, the convict or military words and finally the flash words of the criminal underclass, or the 'thieves' cant', a kind of secret code allowing criminals to speak aloud in the presence of police and magistrates without being understood.

Convict fraudster 'Flash Jim', who was actually transported to Australia three times, deserves a book to himself and one was actually published by author Kel Richards only in 2021.

But now to other matters. We don't hear much more about Skottowe because of his short life. He'd been appointed the Newcastle penal settlement commandant by NSW colonial governor Lachlan Macquarie at the age of 24. Skottowe was later transferred to military duties in then Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), became sick, and returned home to England, where he died aged 33.

Before that, he fathered a child called Augustus John with Mary Ann McCarthy and then a second son, George Thomas, was born to the unmarried couple in 1814 in Newcastle. But when Skottowe's regiment left for Ceylon in April 1815, he was accompanied by his elder son, Augustus John, but not his common-law wife, Mary, or George Thomas.

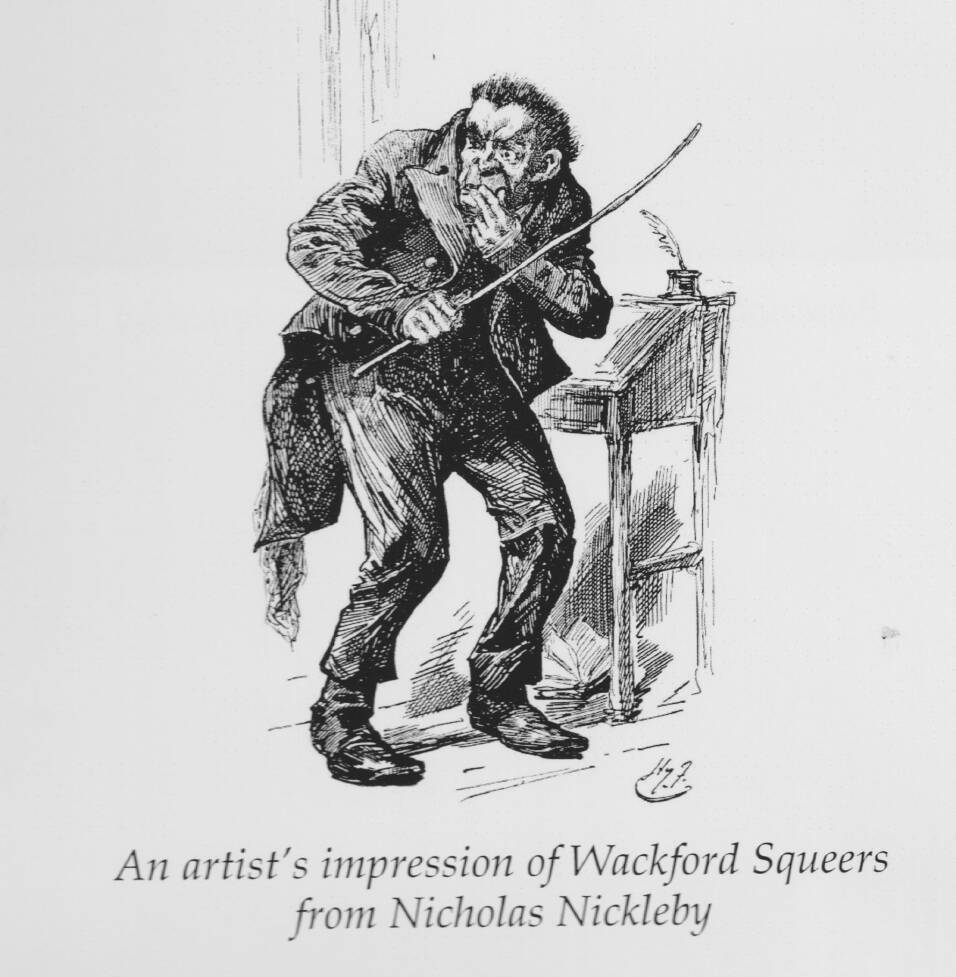

George disappears from history, but, according to Dutton's diligent research, a sad fate awaited Augustus who apparently was not welcomed by the Skottowe family. Thomas's bastard son was regarded as an embarrassment after his father's death in 1820. At age nine, he was bundled off to a notorious boarding school in Yorkshire that is now seen as the model for a brutal school in the novel Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens. Talk about art imitating life. The evil one-eyed headmaster was prosecuted and fined for the mistreatment and malnutrition of students, but somehow kept his job. Amazingly, between 1810 and 1834, about 25 boys aged from seven to 18 died at the school.

These are some of the fascinating facts that emerge from Dutton's booklet. Another is the surprising link between the Skottowe family in England and the great explorer and navigator James Cook. It seems the family encouraged the young Cook to join the Royal Navy, and the rest is history.

Dutton's book, I would suggest, is not for the general reader as it meanders too much for my liking, but it's a rewarding read for those with an interest in how diverse family histories can be.

One of the story threads that Dutton pulls together at the book's end concerns Captain Cook. How extraordinary for a yarn that began in convict Newcastle (with the Skottowe family earlier mentoring a promising seaman) should conclude with Frank and Margel Hinder's magnificent water sculpture in Civic Park began in 1966. Four years later it was named the Captain James Cook Memorial Fountain to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Cook's exploration and mapping of the east coast of Australia.

The book then ends on a poignant note. You have to admire the strength of character and business astuteness of Mary Ann McCarthy to survive and thrive in the cutthroat 19th century.

Abandoned by her common-law husband, Skottowe, and 64 years since she had last seen her son, Augustus, she obviously never gave up hope that one day that family might be reunited. That would seem to explain then why she is buried alone in a double family plot at Sydney's Waverley Cemetery.

Her hope was carried to the grave.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on the Newcastle Herald website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. Sign up for a subscription here.