It's TB-303 day - 3rd of March, geddit? - so celebrate by enjoying this classic 1996 interview.

By 1996, Giorgio Moroder was already legendary, having been a towering influence on the births of both disco and electronic dance music. He’d also (quite literally) scored considerable success with his film soundtracks, and worked with everyone from Phil Oakey to David Bowie, Elton John and Cher.

There was plenty for Future Music’s Matt Overton to discuss with Moroder when they sat down for a chat, then - here’s the full interview from FM51 (December 1996).

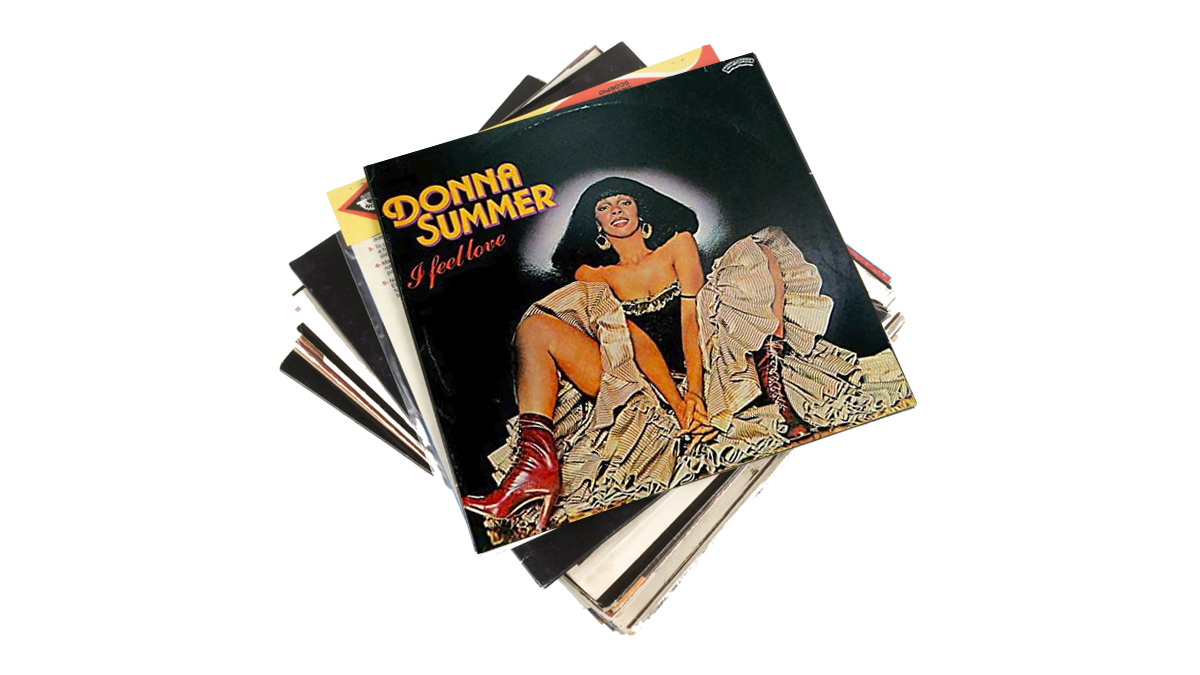

Forget punk, my memory of 1976 was my (rather groovy) father playing Donna Summer's Love To Love You Baby. A year later he was at it again with I Feel Love. I only have to hear that bass sound, that repetitive electronic percussion, that groaning and moaning for the hair to start to rise on the back of my neck.

If there are two records which made me aware of the power of synthesized disco music, it was those. And they marked the first steps on a long musical journey by one of the men behind Donna Summer: Giorgio Moroder.

Since then he's written or produced over 40 songs for films (one of which won an Oscar) and scored 15 films. He has been awarded two Grammys, three Academy Awards and four Golden Globes (and has been nominated for a further two). He has over 100 Gold and Platinum discs. He's written the theme songs for two Olympics and one World Cup (in his native Italy). In addition, he's co-written a Broadway musical and is presently working with Michael Jackson on his film Dr Lao. And, if this isn't enough, he helped with the design of a 16-cylinder supercar, the Cizeta-Moroder…

The 40 greatest synth sounds of all time, No 3: Donna Summer - I Feel Love

You've been involved in writing songs and soundtracks for films, as well as giving birth to disco. But they seem to be poles apart...

“Yes, they are. But they're also related. I did I Feel Love with Donna Summer and Pete Bellone, and it was a hit. But you would never have imagined that a disco song would trigger the mind of Alan Parker [director of Midnight Express] who liked the sound - that's how I got started in the movies.”

Was there any resistance to you scoring films because of your background in disco?

“No, not at all. In fact, I met Alan, Peter Guber and the owner of Casablanca Records and they liked the idea. I did a little demo recording of some tunes, played it to Alan and he loved it. But I'm not saying it was easy. We recorded the soundtrack to Midnight Express in Munich and mixed it in one day - that was quite unusual.”

Did winning an Academy Award for Midnight Express so early on in your career put any pressure on you?

“No, it helped me, because that sound 'worked' for two or three years. But it was a little bit of a curse, too, in that as soon as the movie came out and after the Academy Awards, a lot of TV guys started to use the same sounds.

“After two years I could barely listen to it any more. It was a little bit of a problem for the third movie I did, because the producer related my musical influences and tastes with loads of synthesizers. A beautiful score with strings and classical instruments: that always works for me. But a score that is just synthesizers wears thin, especially on TV - they use it so often that people say, ‘Enough, enough!’ So that’s a bit of a problem with me since that’s the only music I can do.”

Do you approach writing a score and a single differently?

“To write a single, if you specifically sit down to write one, you have to know what the range is, what type of song, so you have parameters ready to work around. For a movie, you have, first of all, to think about the movie: you have to fit the movie, fit the mood. Then, later on, you think, 'Should it be a girl or should it be a guy singing?' Then who sings it becomes the second part.

“Sometimes it's not easy to connect the two things. For instance, with Take My Breath Away [that pretty neat theme tune from Top Gun - Ed.] we had some guys in mind at the very beginning and one famous guy, who l won't mention, passed on it. Then we thought we should do it with a female and we ended up with Terri Nunn of Berlin. So it's quite different, actually.

Did you make I Feel Love especially for Donna Summer?

“Yes. That was an album where we wanted to have a concept - where we had one ‘50s song, one ‘60s, one ‘70s, one Motown - and we wanted to have a futuristic sounding song: I Feel Love. At that time, I was a little fed up with synthesizers, which I'd started to use in early 71, but the only way to get futuristic sounds was to use synthesizers - that wouldn't work now.”

Have you heard the remixes of it?

“I heard several versions of it. Some were good; one particular mix I liked a lot. If they change the chords, usually it's not for the better. But in this particular case the guy changed one particular chord and I thought, 'Wow,I should have done that!' So that was quite good.”

You've recently remixed Heaven 17's Designing Heaven. What was that like?

“It reminded me of my old sound, not necessarily the melodies which were quite different to those I would write, but the tempo reminded me of my past, so it was relatively easy. I’ve remixed people in the past: The Eurythmics' Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) was the first one in 1991. I've done about ten remixes now.

One of Heaven 17's own mixes is like one you did... Did you hear the track in its finished state?

“We got the 24-track tape, but I think we heard only one mix - I don't really remember.”

Because Heaven 17 had done some mixes of their own and one of your mixes is close to how they’d done it…

“That’s interesting. It’s a good sign, actually - it means we were on the same wavelength”

That's basically what Heaven 17 said. If you hear the other remixes, the chords have been changed, the tempo has been speeded up or the track has been stripped down. Yours keeps the flavour a lot more.

“I haven’t heard the others, but there are some times where remixes change the original too much.

And two of the members of Heaven 17 used to be in The Human League - and you've worked with Phil Oakey…

“Yes, I did a whole album with him. That’s a funny coincidence! I never met Heaven 17, and I only met Phil and the two girls - the backing singers from the group.”

What was it like working with Phil Oakey?

“Very nice. We're talking 12 years ago, but he's a very nice guy, very professional. I think I wrote most of the songs for Electric Dreams and I think he wrote all the lyrics. It worked quite well. He's a great singer, he was well prepared; if you write the lyrics then you should know the song, but some singers come in the studio and they don't know the song at all. That wasn't the case with Phil.”

Together In Electric Dreams was included in an album of early ‘80s electronic songs, called Electric Dreams, promoted on TV…

“That's funny, because just yesterday I listened to a remake of the song by a Canadian group, Contact, who did quite a good job actually; it was quite nice. But the version with Phil is still the best.”

You've worked with Sigue Sigue Sputnik as well.

“Ah, that was quite an, er, adventure. We had a lot of fun - God, crazy guys.”

Who’ve you most enjoyed working with?

"Practically everybody - I wouldn't say one. Like Elton John and RuPaul: we did the whole recording in two hours. And David Bowie - we started at 9.30 or 10 o’clock in the morning and it was done an hour and a half later, which is quite unusual. The real professionals, great superstars, they just do it three times, sometimes just once or twice, and it's there. So it’s quite nice to work with professionals.”

David Bowie - we started at 9.30 or 10 o’clock in the morning and it was done an hour and a half later, which is quite unusual.

Is it easier to work with new or established artists? Do the latter dictate a working method?

“Yes, to sum it up. I did a song ten years ago with Cher. I was told before that she may not be punctual and she may be an hour or two or five hours late. But, to my big surprise, she was there on time. I said, 'Wow! I'm shocked you're here.’ She said, 'Yeah, for the first recording I am,’ meaning for the second one she may be late. You have to adapt.”

What's your view on modern technology? You've seen everything change from analogue to digital.

“I like it. I use [MOTU] Digital Performer for my sequencing. I don't have time to spend building sounds.”

But you're associated with a very analogue sound due to your disco heritage.

“I'm quite happy to be associated with that sound, and with its revival. But in a non-dance song I would use sampled basses. If you want to make a good dance song, though, you still need the 303, an analogue drum machine (instead of a nice sounding digital one) and a Minimoog.

“I rely on things in Digital Performer. You can put a vocal in, for example, at 100bpm and tell the computer to make it 110bpm. You come back five minutes later and it's done. And there are three-dimensional effects: you can slow down the tape in real-time but not change the pitch. I've had a go with virtual sounds, especially woodwind, on the Yamaha VL-1. That's going to be great in the future.

“But, in general, I try to stay away from all the new stuff. You have to really know it well. But I don't have the time, really the desire, to learn - there are too many details to make it work so I prefer to have my musicians know it.”

You're more of a hands-off producer, directing people to do things, co-ordinating the process…

“I do demos and I use my sounds - some are great, some are plain. Then my musicians take it and add the detail. I’ve worked this way all my life. I’ve rarely done a whole recording by myself.”

You've been involved in the music industry for three decades. What's your advice to someone who wants a career like yours?

“Get a good manager or agent - I didn't have one until a few years ago. It does cost a lot of money but you need someone to fight for you. Also, it's tough for someone to say to someone else, 'No, I don't want to produce you,' because it becomes personal. But a manager can explain it and it's less direct than saying no. Competition is fierce so you need someone on your side to look for jobs and keep the momentum up.”