Between 2017 and 2021, 40% of Chicago traffic accidents in which pedestrians were seriously injured or killed involved motorists making a left turn.

That’s why the city says it has been taking steps to make those turns safer.

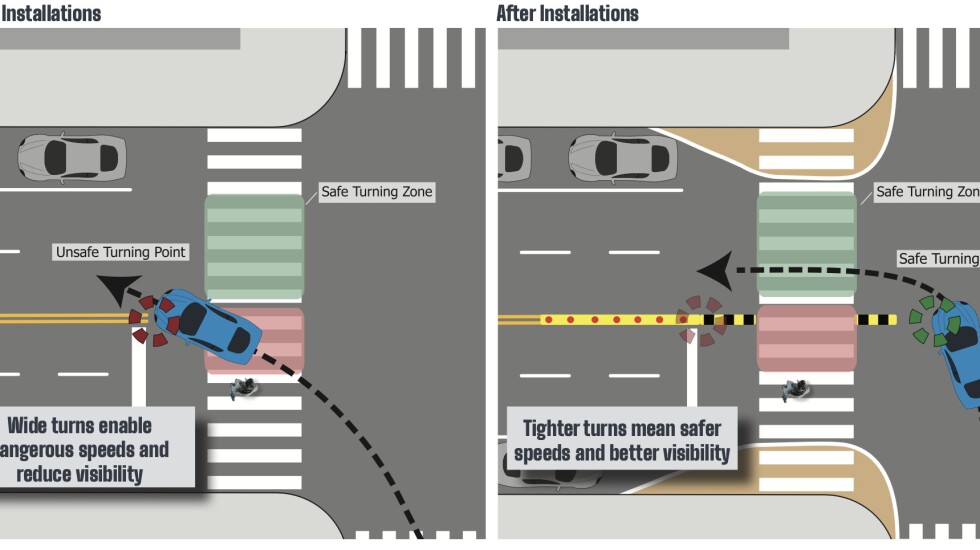

It’s called “traffic calming,” and it involves adding larger speed bumps and bollards (plastic posts on a flexible base) along the center line near a crosswalk.

The idea is to force slower, 90-degree-angle turns and prevent drivers from making faster turns at a smaller angle that cut across oncoming traffic lanes. The ultimate goal is to better protect pedestrians in the crosswalk, who often end up in drivers’ blind spots on those left turns.

In Belmont Cragin, Englewood, Humboldt Park, Ravenswood and other neighborhoods, drivers are greeted by rubber speed bumps with the bright yellow bollards on top, like those used to separate bike lanes.

Thirteen intersections were modified by the city last year. A total of 18 intersections now have been altered, including five during a pilot program begun in 2019.

Plans call for changing even more intersections this year, focusing on sites with high rates of accidents involving drivers turning left.

The measures have caused some confusion, as Twitter user @lefthandedranda observed last year: “Everyone pray for my Uber driver. Nothing’s wrong he’s trying to make a left turn in Chicago.”

Others believe the barriers, since they are easy to run over, aren’t strong enough to make a difference.

“Those things need to seriously damage a car to have any effect on driver behavior,” one Twitter user, @will_be_biking, wrote in September. “Plastic ‘bollards’ do nothing.”

“Those things never stand a chance against large trucks in the city,” @toombsday tweeted in January.

Crashes at those five pilot sites in River North, along State Street between Hubbard and Ontario streets, have dropped 24% since 2019.

The traffic calming is just another component of the city’s Vision Zero safety campaign, begun in 2017 with the goal of eliminating traffic fatalities in the city by 2026.

On average, five people are seriously injured in traffic accidents in Chicago every day, according to data collected by Vision Zero.

Over the years, in various locations, the city has installed other measures to slow traffic and protect pedestrians, including cul-de-sacs, alley speed bumps and traffic circles.

“So far the results have been positive,” CDOT spokesperson Erica Schroeder told the Sun-Times, “with data showing drivers making safer turning movements, yielding to people in crosswalks, and overall crash reduction at intersections.”

The Transportation Department sought recommendations from City Council members to help decide which high-risk intersections to modify first.

Of the city’s 50 wards, the 47th, represented by Ald. Matt Martin, spent the most money on traffic improvements last year. At least one other Council member has reached out to Martin for advice on bringing more of the left-turn modifications to their ward.

“We were focused on our more dangerous streets from the get-go,” said Josh Mark, director of development and infrastructure for the 47th Ward. “Traffic safety and pedestrian safety have been our No. 1 priority.”

Mark said driver feedback in the 47th Ward has been more positive than expected, given that “initially, when you make changes to traffic flow … it can be a little bit difficult for drivers.”

Still, the online complaints continue.

“I have no idea why they insist on throwing money away on makeshift fixes like this,” wrote Twitter user @litwicki in September.

Kyle Lucas, co-founder of Better Streets Chicago, a transportation advocacy group, said the barriers are easily damaged, and dislodged pieces can land in an intersection, causing other problems.

“To me, they’re a Band-Aid,” Lucas said.

Last year, Lucas said, he often saw drivers slow down as they approached the yellow plastic barricades on State Street. But any confusion — and slower driving — was short-lived, he said.

It’s “a good way to rapidly roll out some initiatives to slow traffic down,” he said, “but I don’t see them as a permanent solution.”

A better, long-term solution, Lucas and other advocates say, would be using concrete barriers to both control turns and protect bike lanes.

While the bollards “are a great way to like test it out,” the downside is “they’ll leave that temporary installation for years at a time with no concrete upgrades being made,” Lucas said.

Feedback also is mixed in other cities that have taken similar measures, including New York City, Washington, D.C, and Portland, Oregon.

Chicago, meanwhile, is planning new speed bumps and barriers at more Chicago intersections this year, Schroeder said, because “making it safer and easier to walk in Chicago is a top priority.”