Almost two-thirds of Australia is privately owned. But most of our scientific understanding of how threatened species are faring comes from research done on public lands. Traditional biodiversity surveys by professional scientists are time and resource intensive and navigating access to private lands can be tricky.

This means there’s a huge gap in our knowledge amid worsening biodiversity loss. That’s where citizen science comes in. Every year, millions of Australian species records are logged by members of the public using smartphone apps. This flood of data is revolutionising conservation, producing large flows of species data and connecting people to nature.

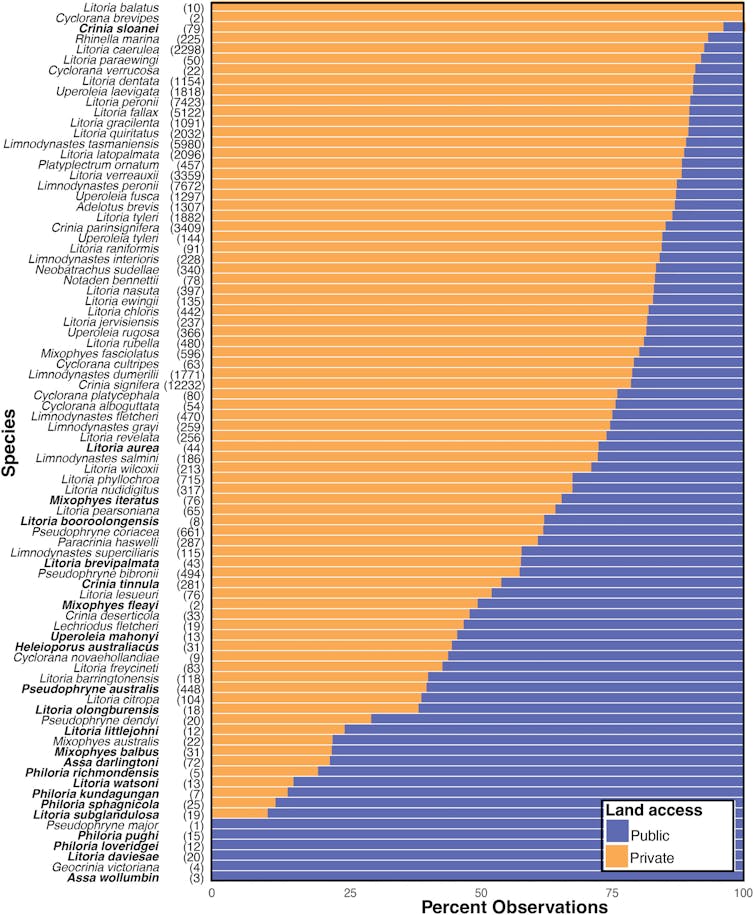

But does this data better capture species on private land? To find out, our recent research examines almost half a million frog records logged on the Australian Museum’s national FrogID project by citizen scientists in New South Wales. Remarkably, 86% of these records come from private land.

Importantly, these records capture evidence of where threatened species are holding on in privately-held land. The beautiful green and golden bell frog (Litoria aurea) is considered vulnerable at a national level as it’s no longer found on about 90% of its former range. But almost three-quarters of all FrogID recordings of this frog in NSW are on private land.

Recordings with a smartphone

Frogs are one of the most threatened groups of animals on the planet. One in five species of Australian frogs – almost 50 species – are threatened with extinction. Disease, habitat loss and climate change are their greatest threats.

At least four species have already gone extinct – including the unique gastric-brooding frogs – while several others haven’t been seen in decades and are feared extinct. It’s vitally important to track how the surviving 240 plus species are faring.

In our research, we analysed the 496,357 frog records logged in NSW on FrogID between 2017 and 2024.

Private lands make up the majority of New South Wales, and cover almost every habitat type. It stands to reason that many frog species should be found across private land. Our analysis of FrogID data found the diversity of frog species was actually higher on private lands than on public lands, which include national parks and other protected areas, once we accounted for differences in aridity and surveying efforts.

In addition, the frog species recorded on private and public lands weren’t the same. Two species were recorded only on private lands and six only on public land.

As we expected, we found that citizen science more comprehensively surveyed public land than surveys by professional scientists, but the difference was more dramatic than expected. Data from professional surveys covered 19% of NSW, while citizen scientists using FrogID covered 35%. There were nearly ten times as many FrogID records as professional records over the same time period.

But the clearest difference was in private lands. A remarkable 86% of all FrogID records came from private lands, compared to only 59% of records obtained via traditional methods.

Frog calls after floods

One of the biggest boons of citizen science is that it can help overcome many of the logistical obstacles associated with traditional professional surveys, particularly for frogs.

Most of the NSW FrogID records come from urban and suburban areas with high human population density. But the data showed an increasing number of landholders in regional and remote areas are using FrogID to record their local frogs.

Obtaining records of frogs from these areas via traditional surveys has long presented a major challenge for scientists. That’s because many frog species in arid and semi-arid areas only become active after heavy rains. But these areas can become inaccessible to scientists due to flooded roads.

By opportunistically recording frogs when they’re active, landholders are providing the vital information we need to better understand poorly-known frog species such as burrowing frogs from the Cyclorana genus and the charismatic crucifix frog (Notaden bennettii).

Private lands are vital to conservation

It’s common to think that threatened species will be restricted to protected areas such as national parks. Our research adds to the body of evidence showing this isn’t the case.

We found 20 of the 24 NSW threatened frog species we analysed had been recorded on private land. In fact, a third of all threatened frog species were predominantly recorded on private land, while three threatened frog species had over 70% of recordings logged on private land.

One such species is Sloane’s froglet (Crinia sloanei), a tiny frog from inland New South Wales and northern central Victoria. Habitat loss has greatly reduced its range. It’s now considered endangered nationally. We found 96% of records were on private land, largely around Albury–Wodonga on the Victorian border. Similarly, the nationally vulnerable green and golden bell frog was largely recorded on private lands.

How can you help?

Private lands are now seen as increasingly important in conserving wildlife, including threatened species. The good news is, this means landholders and citizen scientists can make a direct difference.

Protecting or creating wildlife habitats on your property can make a very real contribution to biodiversity conservation. Even humble farm dams can support threatened frog species.

While citizen science has greatly improved our knowledge of frog species across Australia including poorly-sampled areas, scientists still need more data on Australia’s frogs.

Recording and uploading the calls of any frogs you hear using the FrogID app is a simple and effective way of adding to our collective knowledge of these remarkable amphibians. The more data sources we have, the better. Citizen scientists are giving real-time updates of where frogs live and how their distributions are changing over time. These data in turn help focus efforts to bring back threatened frog species from the brink of extinction.

Jodi Rowley is the Lead Scientist of the Australian Museum's citizen science project, FrogID. She has received funding from state, federal and philanthropic agencies.

Grace Gillard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.