On the final day of March last spring, Chicago Public Schools officials abruptly yanked a principal from his school and sent a letter to families and staff revealing an investigation had resulted in “substantiated findings” against him.

School district leaders insisted they couldn’t say more because of privacy concerns, leaving the school community at Lindblom Math and Science Academy hanging on TV news reports with rumors and little information about what the principal had done. The principal said he was left devastated and ashamed, especially because his daughter attended the school he led.

After months of inquiries, WBEZ and the Chicago Sun-Times obtained detailed information last month about the Lindblom principal’s case — and it reveals his removal was based primarily on procedural and bureaucratic violations. The investigative report raises questions about probes led by CPS attorneys, the school district’s aggressive tactics for removing principals and whether the highly disruptive actions are always justified.

The Lindblom principal is one among several who have been removed. And these aren’t just any principals.

In the past four years, nine principals have been removed pending discipline or investigations into “serious misconduct,” according to CPS’s response to a public records request. Of those, six are Black men — who are already scarce among principals. The remaining three are a Black woman, a white woman and a white man. CPS didn’t list several more principals, including the one at Lindblom, because they were either interim, left while under investigation or were immediately fired.

CPS officials defend the removals, saying the district has “comprehensive procedures” to investigate staff misconduct allegations. They say principals have opportunities to defend themselves, and CPS is “confident in the decisions made by the leaders of our District.”

The school system has “an obligation to investigate misconduct and act appropriately when misconduct is substantiated,” CPS spokeswoman Mary Fergus said in a statement.

“We recognize that removing a principal is very disruptive to a school’s community and is therefore done so only when the misconduct makes it necessary.”

Scrutiny of CPS’ actions

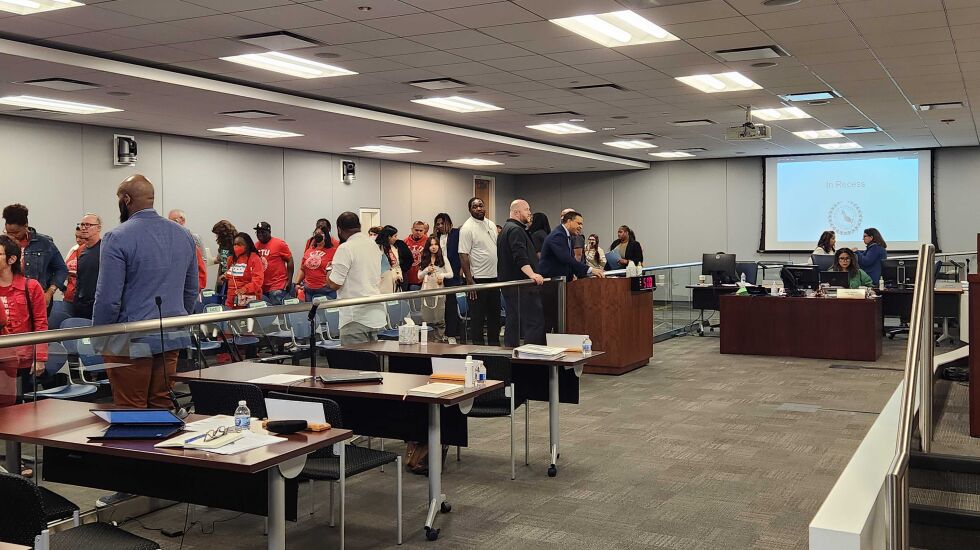

Four recent removals have led to complaints that CPS is targeting Black principals. Troy LaRaviere, president of the Chicago Principals & Administrators Association, has been escorted from two recent Board of Education meetings as he yelled at CPS officials, accusing them of corruption.

Those frustrations boiled over in July when prominent national civil rights attorney Ben Crump came to town to protest outside CPS headquarters.

“Give these Black leaders a fair proceeding where they can show that they have been falsely accused, and they can exonerate their good names, and they can get back to doing what they love to do, and that is educating our children,” Crump said.

In response, a CPS spokeswoman highlighted that 44% of principals in CPS are Black — more than any other group in the system. CPS officials say they also provide plenty of guidance and professional development to new principals. Asked about these complaints, CPS CEO Pedro Martinez said each case has “specific circumstances,” and he is “very proud” of principal diversity.

Harrington Gibson, director of National Louis University’s doctoral program on educational leadership, mentors Black male principals in CPS — a group he said is woefully underrepresented. Only 9% of CPS principals are Black men while 18% of students are Black boys, according to state records. Studies show that students perform better when they see themselves in teachers and school leaders.

Given that, CPS needs to explain the racial disparity in principal removals, Gibson said, and give Black men in leadership positions room to safely talk about challenges.

The Lindblom case

The most prominent case is Abdul Muhammad from Lindblom, a high-performing selective high school in West Englewood on the South Side. CPS has not provided any additional information about the nature of allegations against the other principals.

Lindblom’s Local School Council hired Muhammad in July 2022, but there were immediate concerns from some corners. Officials point out he transitioned from running one of the district’s smallest high schools with fewer than 100 students to leading a top-ranked school of 1,400 children. Some students immediately protested his dismissal of a beloved assistant principal. And there were separate worries from staff — including that he didn’t show a “willingness to adapt to school culture.”

CPS officials didn’t give him a contract when Lindblom’s Local School Council — whose most important job is to hire and evaluate a principal — voted to offer him one soon after he arrived. That left him in a precarious position, employed at-will as an interim principal.

The staff complaints turned into a 10-page document presented to the school board in December.

Muhammad says he thought he was doing a fine job through that time trying to implement his vision for the school. He feels he was targeted from the start — held to a higher standard and scrutinized more heavily than his peers because he’s a Black Muslim.

Several LSC members said they thought he was doing well and continued to support him.

Ultimately, the district pulled Muhammad on March 31, telling students and staff in a letter that they “removed Abdul Muhammad from his principal duties at Lindblom effective immediately due to an investigation that substantiated findings against Mr. Muhammad.”

Without more details, that letter set off speculation at the school.

WBEZ and the Sun-Times submitted public records requests in early June seeking more information about Muhammad and the other recent principal investigations. The district refused to respond for weeks.

But under pressure the day before Crump’s news conference, CPS responded with a sprawling, 61-page investigative report on Muhammad produced in March by an attorney in the district’s law department. (They didn’t provide any details on the other principals by our publication deadline, citing ongoing investigations.)

It showed that CPS found “evidence” to support 18 allegations against Muhammad, including:

- “Odd hiring practices,” like creating three new positions without disclosing hiring procedures.

- Failing to heed concerns that a severely disabled special education student endangered staff, including an incident where the student allegedly disrobed and rubbed their genitals on teachers.

- Failing to background check entertainers for a pep rally.

- Failing to train staff on how to report safety incidents in CPS’s system.

- Allowing “critical inaccuracies” in special education procedures and record-keeping to continue.

CPS attorneys also looked into whether Muhammad failed to report a complaint that a security guard sexually harassed a student, the report shows. CPS included three findings related to the charge that Muhammad mishandled that issue, including that he violated a mandated reporting policy.

In an interview with WBEZ and the Sun-Times, Muhammad strongly refuted the findings, particularly his alleged failure to report sexual misconduct and the accusation that he downplayed teachers’ safety concerns about the severely disabled special education student. Muhammad said he followed the proper protocols by directing staff to report the sexual misconduct claim and started discussions about removing the student with special needs — a sensitive process that doesn’t happen overnight.

Muhammad admitted to some of the special education management problems but said they were largely the doing of an inexperienced special education case manager who apologized for mistakes and took Muhammad’s offer of a mentor.

In the end, CPS temporarily reassigned Muhammad to a regional office, suspended him without pay for five days and gave him two months to “seek new full-time roles within CPS.” He was invited to apply for other positions in the district. CPS says the final discipline decisions are made by senior leadership and not the law department.

Was the punishment warranted?

A further examination of the CPS investigation gets to the heart of the case: Did the complaints about Muhammad’s management warrant such an aggressive set of actions by CPS that it overruled a Local School Council that wanted to keep him, resulted in the loss of his job at Lindblom and sullied his reputation — or could CPS have pursued less punitive measures?

CPS’s Law Department oversaw this investigation because it’s charged with responding to some allegations of employee misconduct related to policy violations, the district said. The law department was involved in five of the nine removal cases CPS shared with WBEZ and the Sun-Times.

But the department should not have investigated the most serious allegation against Muhammad — his handling of alleged sexual misconduct, according to CPS rules. Those were established in the aftermath of a scathing 2018 Chicago Tribune series and subsequent district review that found the CPS Law Department had systematically mishandled sexual misconduct claims for years. Since that scandal, which resulted in a federal court-ordered reform plan, the CPS Inspector General’s office took jurisdiction over all adult-on-student sexual misconduct cases.

CPS officials firmly denied their attorneys investigated Muhammad’s alleged failure to report sexual misconduct. That’s even though the district’s report included substantiated findings on that issue.

“Any reports or allegations that the CPS Law Department Investigative Unit (LIU) overstepped its role in the investigation of this former employee is factually inaccurate, and to report or suggest otherwise is incorrect and unfairly informs your readers and listeners,” Fergus, the CPS spokeswoman, said in a statement.

The Law Department investigator “rightfully collected the necessary information to refer the case” to the inspector general, Fergus said. The inspector general’s separate investigation is ongoing.

Will Fletcher, the CPS inspector general, declined to comment.

Joe Ferguson, Chicago’s former inspector general, was critical of the law department’s role in a case like this. He said law departments generally do not conduct investigations in the manner of an inspector general’s office because they prioritize managing litigation risk, harm to organizational reputations and politics. The investigative report in Muhammad’s case did not appear to be thorough and lacked interviews with corroborating witnesses, he said.

“The lens of the law department is risk management and from the perspective of leadership a damage control approach,” Ferguson said. “That’s all very different from an [inspector general] whose job is to gather all the evidence and let the facts fall where they may.”

Neither Muhammad’s alleged failure to report sexual misconduct nor the case involving the special education student ultimately factored into his discipline. A letter sent to Muhammad in March and shared with WBEZ and the Sun-Times last month shows only six of the original 18 “substantiated findings” are cited, including background check violations and continued special education inaccuracies.

But it’s unclear whether these procedural and bureaucratic infractions alone rise to the level of removing a principal. In a statement, CPS said principals “may be removed or ‘pulled’ due to serious misconduct investigations or while in termination proceedings.” CPS did not define “serious misconduct.”

CPS says district leaders consider each case and the CEO makes a final decision. But there’s no publicly available standard for disciplinary outcomes.

Because Muhammad was an at-will principal who was reassigned to another position, CPS does not consider him to have been “removed” or “pulled,” according to the district’s definition. But he nevertheless was taken from his job at Lindblom.

In the end, Muhammad did not have the option of returning to Lindblom as the principal. But officials told him he would not be placed on a “Do Not Hire” list for employees who were dismissed due to serious misconduct investigations.

Muhammad’s attorney, Sa’ad Alim Muhammad, said the damage to his client’s name can’t be undone.

“His whole life has been turned upside down at this point,” the lawyer said. “I mean, 25 years down the track, and just to have it derailed. … That’s an injustice, that’s a travesty. People are making decisions that are disrupting households.”

Natasha Erskine, who leads the parent group Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education, said she has seen the school district provide support to struggling principals rather than remove them. She said CPS should empower LSCs and hopes the district didn’t overstep in this case.

Most of all, she worries about the turbulence Muhammad’s abrupt removal has created.

“It has a ripple effect,” Erskine said. “Some of our most engaged parents are usually not going to stick around for this mess.”