In 1835, the Cherokee Nation was promised a delegate in Congress as part of the same treaty – Treaty of New Echota – that led to the death of thousands on the Trail of Tears. Nearly 200 years later, the Cherokee are still fighting to make that promise a reality.

“The Treaty of New Echota is a living, valid treaty, and the Delegate provision is intact because it has never been abrogated,” Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin wrote in testimony submitted to the House Committee on Rules on Nov. 16, 2022. “As the Supreme Court has made clear on multiple occasions, and as the landmark McGirt decision reaffirmed, lapse of time cannot divest Indian nations of their treaties and treaty rights.”

McGirt is the 2020 Supreme Court case that reaffirmed that the reservation boundaries of Muscogee (Creek) Nation survived Oklahoma statehood and remain in effect today. This decision, coupled with a follow-up decision, upheld the reservation status of the Cherokee Nation and four other tribes.

If the Cherokee Nation is successful in its bid, Kimberly Teehee, the nominated delegate, will join delegates representing the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam and other U.S. territories as a nonvoting member of the House.

As a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and a historian of Cherokee history and social welfare, I think it is important to acknowledge that the idea of a Cherokee delegate is not new. Rather, it is based on hundreds of years of Cherokee negotiations with European colonists and the U.S. government – negotiations that were built on Indigenous diplomatic tools as much as European ones.

What’s more, it is an opportunity for the U.S. to honor its treaties and affirm its government-to-government agreements with the Cherokee Nation.

Indigenous origins

Before the colonial period, more than 500 different Native tribes lived in what is now the United States. When conflicts arose among the various groups, Native peoples used diplomatic tools to address them.

The Chickasaws and Muscogee, also known as the Creek, appointed individuals known as micos to maintain diplomacy and peace within and among Native nations. When the French arrived, they accepted and abided by the mico system.

Similarly, by the early 19th century, Cherokee Chickamauga warrior Major Ridge – and later his son John Ridge – served as representatives to the Muscogee Council even though Cherokees fought against the Muscogee throughout the 18th century.

Adaptations

Representation has always been important in Native nations’ dealings with European settlers and their decedents.

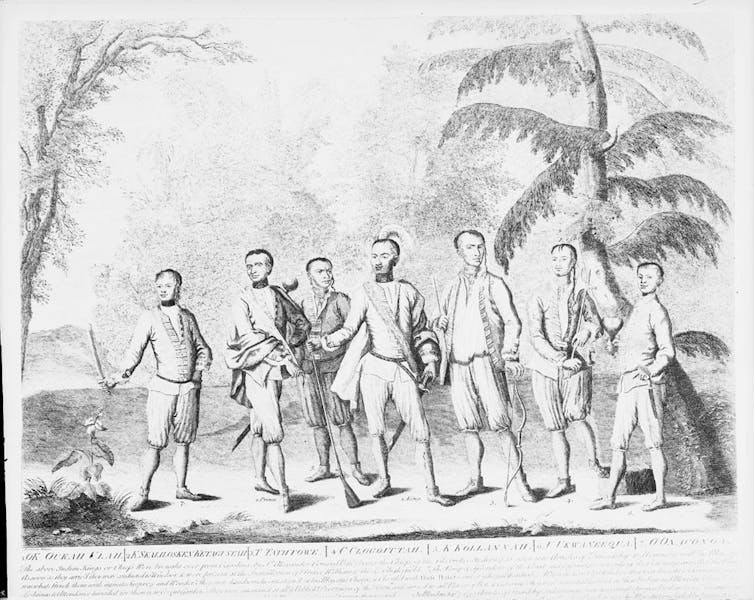

As early as 1730, Cherokee chiefs met with King George II to finalize a treaty.

The 13 newly united states ratified their first treaty with a Native nation in 1778. The Treaty of Fort Pitt, also known as the Delaware Treaty, included a provision for a delegate should the Delaware Nation ever form a state and join the fledgling union – an idea that has not yet come to pass.

In 1785, the Cherokee Nation signed its first treaty with the United States, the Treaty of Hopewell, which built on the precedent set with the Delaware by offering representation to the Cherokee.

New challenges

Although the relationship between Native tribes and European colonists began with some degree of respect and mutual accommodation, that power dynamic shifted as more white settlers arrived.

As the colonies grew in population, land speculators, slaveholders, settlers and Southern politicians were eager to see the federal government remove tribes, including the Cherokee, from their ancestral lands.

Using the same methods as Americans had to assert their independence, Cherokees fought back by writing their own constitution in 1827, intentionally including features of the U.S. constitution and reasserting the Cherokee Nation’s legal rights to its communally held lands.

This sovereign act angered Southerners. Andrew Jackson, elected President in 1828, strongly supported removal. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1829, increasing pressure on Native nations to exchange territory in the east for lands west of the Mississippi River.

Still believing in the power of the pen, the Cherokee Nation next attempted to use the U.S. legal system to resist removal. In 1832, the Supreme Court in Worcester v. Georgia upheld their sovereignty as “a distinct community occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force.”

Everyday Cherokee people didn’t support removal; their leaders understood it didn’t make financial sense. But the U.S. government didn’t respect this majority view. Instead, the government resorted to negotiating the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 with a Cherokee political faction, led by the Ridges, who lacked the legal standing to finalize it.

The traitorous pact threw the tribe into political upheaval. Although Article 7 of the treaty articulated the rights of the Cherokee Nation to appoint a delegate to Congress, the people were in no position to press for this right to be recognized.

Why not then

The negative effects of the treaty were both immediate and long lasting.

In the short term, it forced 16,000 Cherokee people off their homelands in the Southeast. An estimated 25% died before, during and after removal from disease, hunger, exposure and trauma.

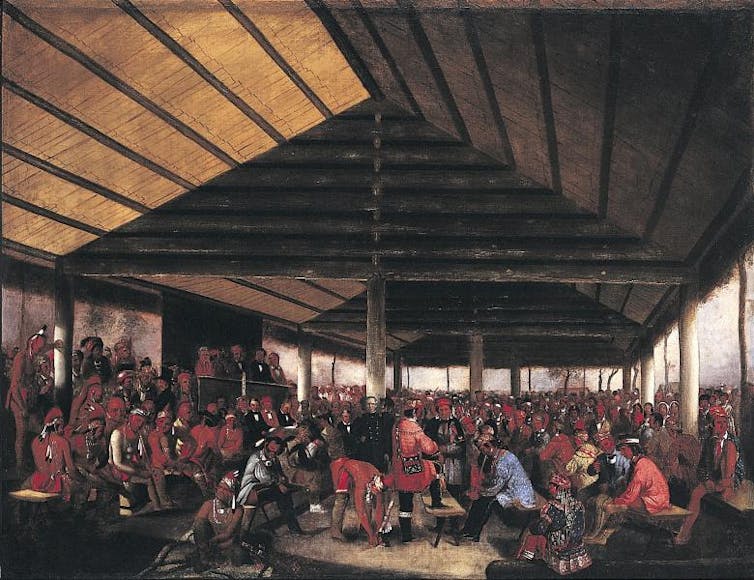

In addition to dividing people from their homelands, removal also divided Cherokees from each other – and brought new Native groups together. A formal council was called in 1843 to establish alliances with other Native nations who were suddenly their neighbors due to displacement.

The U.S. Civil War disrupted these efforts. Some Cherokee people fought for the Union; others for the Confederacy – and that reopened removal era tensions.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government reaffirmed its relationship with the Cherokee Nation in a new treaty signed in 1866. The final article maintained the Cherokee Nation’s right to appoint a delegate to Congress.

Additional challenges

Despite the United States’ treaty promises to keep settlers out of Indian Territory, illegal settlement by U.S. citizens created new legal battles.

The 1887 Dawes General Allotment Act aimed to break up tribal communal landholding.

The Cherokee Nation sent delegations to Washington, and they were able to successfully resist this process for another 12 years, but despite their efforts, the 1898 Curtis Act led to the allotment of the Cherokee Nation. In other words, the federal government revoked some of its treaty responsibilities by breaking up the land the tribes held collectively into individual plots and creating the state of Oklahoma.

Still committed to representation, Native leaders held a Constitutional Convention and proposed the State of Sequoyah, which would exist side by side with Oklahoma. The effort failed largely because the Republican-led Congress opposed the possibility of adding two new Democrat-led states at the same time.

Allotment and Oklahoma statehood plunged Cherokee people into abject poverty, forcing many to turn to itinerant labor.

Why now?

In October 1870, the editor of the Cherokee Nation’s newspaper “The Cherokee Advocate,” after hearing about threats posed by railroads and those seeking to establish U.S. territories, wrote: “The danger, though successfully resisted for the time, is by no means past. The necessity of sending delegates to Washington, D.C. still exists and they must continue.”

That sentiment is still held by many Cherokees today almost two hundred years later.

Since the 1970s ushered in President Nixon’s Self-Determination policy, the Cherokee Nation has launched another phase of rebuilding, enhancing its economy and expanding tribal government and services.

Today the Cherokee Nation comprises more than 440,000 citizens, some of them Delaware. Its population exceeds that of Guam and trails Wyoming by roughly 140,000.

In 2022, the Cherokee Nation is asking for Congress to seat its delegate, as the Treaty of 1835 requires and for which the Cherokees have fought by legal and diplomatic means since before the U.S. existed.

Julie Reed has received funding from various organizations for consulting work on Cherokee history including New York Historical Society, Cherokee Nation Businesses, and various k-12 textbook producers. She has also received fellowship and scholarship support from the Spencer Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, and the Cherokee Nation Education Foundation. She is citizen of the Cherokee Nation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.