What links a Renault factory that takes cars apart, a tough problem for NZ metal recyclers, and a Dutch pesticide maker? Answer: A more sustainable way of looking at the stuff we use and consume

The French town of Flins-sur-Seine, 40km west of Paris, has a cute church, that compulsory chateau (now a municipal building), and, since 1952, the biggest Renault car factory in the country - 237 hectares, or 585 football fields' worth.

Over the years the plant has built some of the French carmaker’s iconic vehicles - the Dauphine, the Clio, the Renault 5, and the Zoe electric car - plus more recently the Micra, manufactured for its Japanese partner Nissan.

But things are changing. Tough economic times for Renault were exacerbated by Covid, and in 2020 the by-then-loss-making company announced 4600 job losses worldwide as part of a $370 billion cost-cutting package. There were rumours Flins would close.

It didn’t. Instead, Renault announced its “Renaulution” - a transformation plan under which Flins is gradually turning from a massive car-manufacturing factory to a massive car-refurbishment plant; what the company is calling a “Re-Factory”.

Instead of making cars, workers will “Re-trofit” used cars to keep them working longer. They will also turn old EV batteries into “betteries” (components for electricity generators), “remanufacture” old car parts so they can go back into the re-trofitted cars, 3D print car components and, if all else fails, send unused materials (mainly copper, precious metals and polypropylene plastic) off for recycling outside the plant.

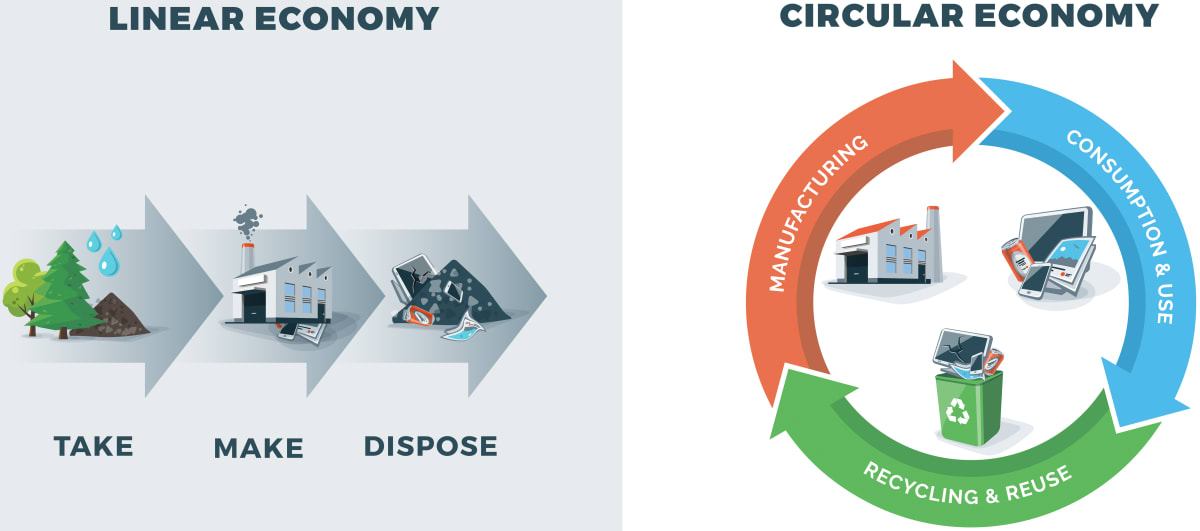

The Re-Factory is “entirely dedicated to the circular economy”, Renault says, referring to an economic model where instead of products moving rapidly from raw material to landfill, the goal is to preserve the value of resources and the things we make from them for as long as possible. The theory is less waste means fewer products needing to be made from new raw materials. And therefore less CO2 and less damage to the environment.

READ MORE: * Circular economy: Breaking our take-make-waste model * What does the future of NZ’s circular economy look like

The aim at Flins is to eventually employ 3000 staff, refurbish 45,000 cars a year and turn 92 percent of materials from scrapped cars into new mechanical parts.

It’s a massive change in thinking. Instead of selling as many new cars as possible, Renault says it wants to keep its old ones going for as long as possible. And it reckons that model will make money in the future.

“Think of it as a big factory doing the work that dealers typically undertake on a much smaller scale,” says Gilles Mériadec, the business director for the facility and a 32-year employee of Renault, talking to the British car magazine Autocar.

“Today our goal is to prove that we can do that job to a higher quality and lower cost because of our specialisms and scale. Today we are breaking even, but in time we must make a profit to survive.”

Win-win for the company and the planet. And hopefully for customers, as long as Renault doesn't use Re-trofit as a way to lock other dealers out of service and repair information and therefore reduce competition and push prices up.

Renault isn't a big player in New Zealand - about 0.2 percent of the market. But even if you happen to own a Renault, it's not going to get it refurbished at Flins. The factory only accepts cars from the Paris region, Mériadec says, because the cost of trucking broken vehicles to the plant is uneconomic from further afield.

“Transport costs are our enemy. We have to make up that deficit by being much more efficient in other areas; 200km is really our outer limit.”

The waste conundrum

The fact that doing the right thing for the environment is so often stymied by distance and cost, even for companies with the right mindset, is one playing out everywhere. New Zealand is no exception.

Take metal recyclers. Their problem is that the Government’s decision to significantly hike the waste disposal levy over four years (a decision the industry supports in principle) could have the unintended consequence of making it too expensive for them to recycle things like cars and household appliances.

The waste levy is a commendable thing - money paid to local and central government by landfills that take public waste as a way to discourage people and companies from throwing stuff away and encourage innovation.

It was originally set at $10 a tonne in 2009, but more recently it became clear that wasn’t enough to achieve its waste minimisation goals.

The Ministry for the Environment hiked the levy to $20 in July 2021, and $30 in 2022. In July this year it will increase to $50 a tonne and a year later it will go to $60.

That 500 percent increase since 2020 worries metal recyclers, not because they don’t think the levy is a good idea, but because such a big percentage of the products they are recycling are to all intents and purposes rubbish that they then have to get rid of.

Take cars. More than 100,000 cars come to the end of their lives each year in New Zealand, according to the Motor Trade Association (MTA). Many of these cars are sent to dismantlers, which remove usable parts, before the frame is transported to a recycler where it is shredded to recover the remaining metal. What’s left is generally sent to landfill.

On average, the waste component of cars and fridges and other appliances, once a metal recycling company has extracted all useable materials, is about 50 percent, says Joe Gibson, president of the NZ Association of Metal Recyclers.

It’s a bit less for cars and a bit more for appliances. But overall, it’s a big percentage.

A lot of the leftover stuff is plastic. A fridge or another appliance contains five or six types of plastic; cars might have more. Then there’s foam, rubber, cables, glass, circuit boards, carpet, maybe some leather, all mixed in with the metals the recycler wants.

Labour costs in a country like New Zealand means it's uneconomic to take a car or a fridge apart. Even if you could, most of the plastic and the other stuff is low value, with no recycle market.

"As the levy increases and if metal prices are low, each recycler has to make a decision." - Joe Gibson, NZ Association of Metal Recyclers

So in most countries, shredding is the easiest way to separate the wheat from the chaff, so to speak. A shredder can reduce a car to 10,000 pieces each smaller than the size of your fist in 30 seconds, Gibson says. A magnet will pick up iron and steel; other systems separate different metals.

The rest is rubbish, which needs to be taken to landfill. At $50 or $60 a tonne, the waste levy is significant, particularly when metal prices are low, Gibson says.

“At $30, when metal prices are strong, the waste levy might not be so much of a problem. But as the levy increases and if metal prices are low, each recycler has to make a decision [about whether recycling a particular item is viable]."

Most metals collected in New Zealand have to be sent overseas for recycling, and that’s expensive. Scrap metal is also a commodity item, so it’s impacted by the international price.

“So you might have scrap selling for US$500 ($780) or it might be for US$370 ($580), delivered to wherever it’s going - maybe India, the Middle East or Pakistan,” Gibson says. "Depending on the steel price, the waste levy is going to have different effects.”

Like Renault in France, the New Zealand metal recyclers are also affected by transport costs. Cars need to be collected from a yard, or appliances from a landfill, and they need to be brought to a shredder, and then the waste taken back to landfill. As fuel and other freight costs increase, so the potential profit for a metal recycler falls.

The situation is worse outside the main centres, where there might not be shredding facilities, Gibson says.

“If you live in Dunedin and you have a fridge to get rid of, you go to the transfer station and maybe pay a fee. Then we come along and collect it and bring it back to the yard in Christchurch for the material to be processed. That’s a lot of distance to cover.

“Or if you are in Napier, where there are no shredding plants, your appliance might have to go to the Wairarapa, or Wellington, even Auckland.

“If the metal price is really depressed, it becomes difficult as a recycler to look at low grade material.”

The metal recycling industry lobbied the government to be exempt from paying the waste levy, arguing its members actually reduced waste to landfill.

“But the government went ahead and we get no relief,” Gibson says.

Richard Harrison, general manager of Phoenix Metal Recyclers, argued in an article on the MTA site that his industry has invested close to $100 million to recover resources from whiteware and cars.

“Higher landfill fees mean there’s less financial incentive for cars to be scrapped and the metals recycled. In practice, this means recyclers may turn away car bodies and whiteware at their gates if they can’t make any money from the items. Where will these items go?”

Possibly, off the bank on the side of the road.

Harrison said for every tonne of car bodies recycled, about 600kg of metal are recovered and the remaining 400kg (plastic, carpeting etc) goes to landfill.

With whitewear, more than 50 percent is waste, meaning they are even less viable to recycle.

Gibson argues that product design - whether it’s fridges, cars or anything else - works against recycling.

Designed for obsolescence

“There’s probably 50 different materials go into a fridge, the same with a car body. How do you pull that apart? If you wanted to recycle everything, you would have to strip it apart, but that’s not viable, and anyway there’s no market for things like plastic.”

For Louise Nash, the founder and chief executive of the sustainable design consultancy Circularity, a radical rethink of product design to make it easy to repair, recover and reuse materials is a key part of meeting our climate change goals.

In 2020, a report from the Circle Economy thinktank, launched at the World Economic Forum in Davos, revealed the amount of virgin material consumed by humanity each year had passed 100 billion tonnes, while the proportion being recycled had fallen below 9 percent.

“The climate and wildlife emergencies are driven by the unsustainable extraction of fossil fuels, metals, building materials and trees,” the Guardian’s environment editor Damian Carrington wrote after the release of the report.

Half of the total raw material consumed was sand, clay, gravel and cement used for building, Circle Economy found, plus other minerals quarried to produce fertiliser. Coal, oil and gas made up 15 percent and metal ores 10 percent. The final quarter was plants and trees used for food and fuel.

“Almost a third of the annual materials remain in use after a year, such as buildings and vehicles,” Carrington wrote. “But 15 percent is emitted into the atmosphere as climate-heating gases, and nearly a quarter is discarded into the environment, such as plastic in waterways and oceans.

“A third is treated as waste, mostly going to landfill and mining spoil heaps. Just 8.6 percent is recycled.”

Nash says the vast majority of goods are designed for obsolescence.

“Companies don’t offer a repair service because they want people to buy their product again. And while some people are dabbling in using recycled material, at the end of life there’s no plan for recovery and reuse.

“Manufacturers say their products are recyclable, but they aren’t recycled.”

Same message from Debbie O’Byrne, circular economy principal at the design and engineering consultancy Beca. The traditional models have left consumers with single-use products we discard at the end of an increasingly short lifespan, she says.

But companies such as Renault are starting to test the water with other design and operating systems which move away from the take-make-dispose model, to something more circular.

“There’s a lot of waste baked in at the design phase - products glued with shitty materials, or companies combining a lot of different plastics so they can’t be pulled apart.” - Debbie O'Byrne, Beca

The idea of “product-as-a-service” is beginning to get more traction overseas, O’Byrne says. Instead of customers buying a fridge, for example, they buy the ability to keep their food cold at home. Often this involves the manufacturer owning the product and the customer paying a use fee.

Because this way the fridge manufacturer has to cover the cost of a replacement fridge if its one breaks, but won’t get any more money from the customer, the theory is it will put more effort into designing a reliable and easy-to-repair appliance.

Moreover, because it has to take responsibility for getting rid of the fridge at the end of its life, it should be more interested in designing something that can be easily disassembled.

“At the moment, there’s a lot of waste baked in at the design phase - products glued with shitty materials, or companies combining a lot of different plastics so they can’t be pulled apart,” O’Byrne says. “They are just kicking the problems down the line for the future when someone has to get rid of the product.”

Product as a service is far from mainstream, but it is being trialled in various industries, from Miele appliances to Caterpillar heavy equipment and Volvo cars. Philips is moving from selling light bulbs (the poster-child product for planned obsolescence) to selling light, and Rolls-Royce from selling aircraft engines to offering airlines contracts where they pay per hour of flying time, and as a function of the engine’s efficiency.

There’s even a Dutch pesticide company, Koppert, that sells farmers a pest-free crop. The idea is Koppert takes care of spraying and the proper application of pesticides, meaning it’s in its interest to use less, rather than more, product.

Europe is “years ahead” of New Zealand, O’Byrne says. Ireland, where she was born, has a Circular Economy Act, passed last July. Amsterdam has a Circular Economy Strategy 2020-2025 tied in with the city’s plans to be climate neutral by 2050.

But New Zealand is starting to go beyond simple recycling and think about issues of product stewardship, for example, she says. And that’s critical, although there’s much further to go.

“We need to see products as material banks.”