Officials in California’s top oil-producing county have a plan for a massive industrial park to produce renewable energy. Kern County says the park will protect jobs and tax revenue threatened by the shrinking oil and gas industry. A county website says it is part of Kern’s plans for a “clean energy future.”

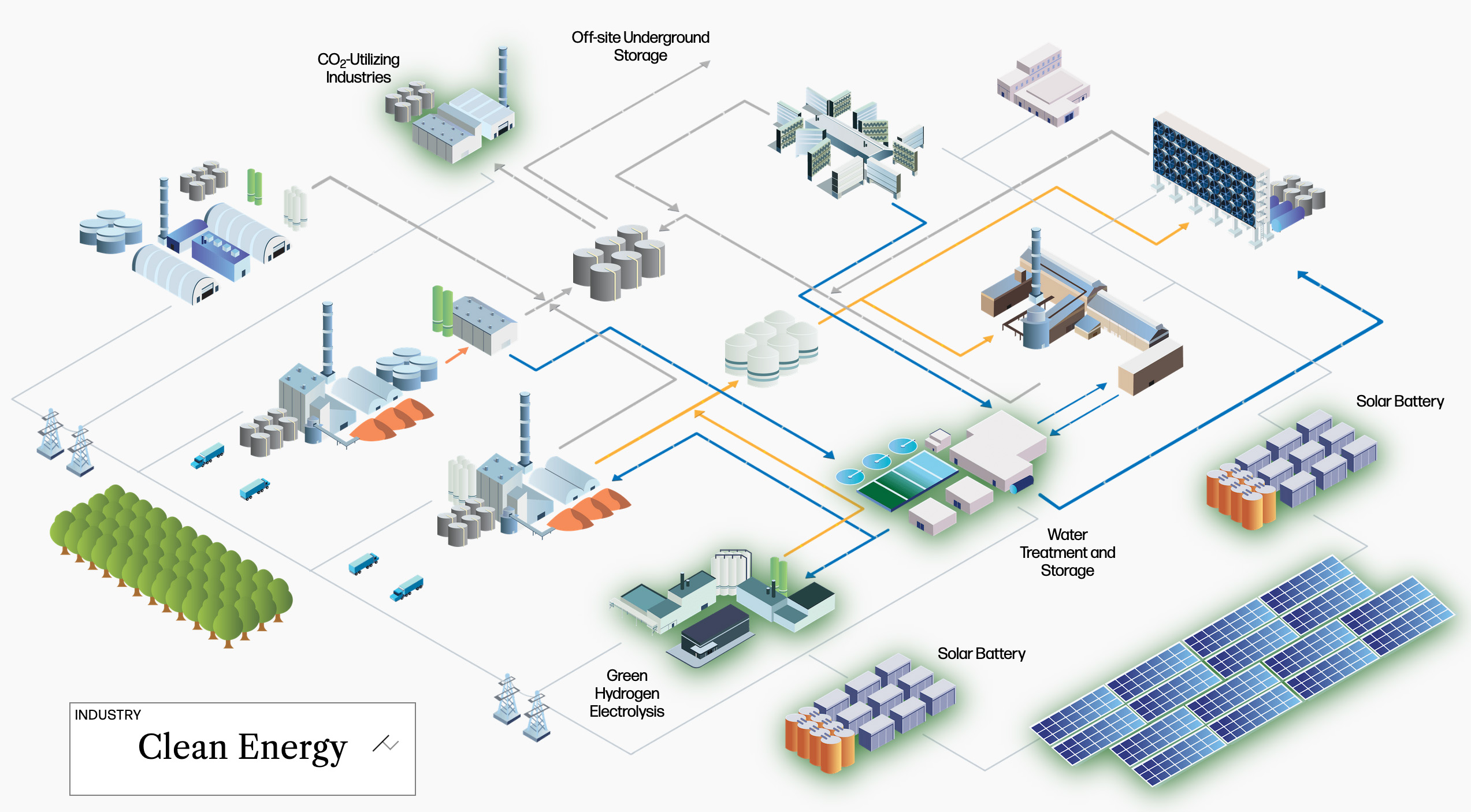

The proposed Carbon Management Business Park would include 47 square miles of solar arrays, more than twice the size of Manhattan. The park could include several businesses, including plants that turn agricultural waste, like nut shells and orchard trimmings, into gas fuel.

But its chief purpose would be to produce carbon dioxide — the most abundant greenhouse gas. County officials want to collect the carbon, which would then be buried in the ground, a process called carbon sequestration. They are hopeful producing carbon could ensure the region’s economic survival as oil production falls.

The money would come from new federal spending for reducing greenhouse gases. Billions of dollars in tax credits for carbon sequestration were made available in the federal Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022, after heavy lobbying from the oil and gas industry. Eager to get a share, groups across the U.S. are coming up with ambitious local plans to capture carbon from power plants, steel mills and other industrial producers — or directly from the air.

Proponents of carbon sequestration tout it as a way to reduce global climate pollution by burying carbon that would otherwise go to the atmosphere and trap heat, worsening the climate crisis.

But critics say Kern County’s plans show how the tax credits for carbon sequestration can create an unintended consequence. To get that money, the county wants to build new plants that would intentionally generate more carbon. Others, primarily oil companies, would then be paid to sequester it.

Projects like the proposed Kern County park would produce clean electricity, but that electricity would be used to produce and sequester carbon. Critics of the project say it makes more sense to simply send that clean electricity directly to consumers.

Carbon sequestration plans like the one in Kern County provide lifelines to fossil fuel producers, according to climate scientists and policy experts.

The solar arrays planned for Kern County’s park would produce enough electricity to keep the lights on in 640,000 homes for a year, more than five times the number of households in Bakersfield.

Research by Stanford University engineering professor Mark Jacobson shows that carbon sequestration produces more air pollution than sending clean power directly to consumers.

Jacobson said Kern’s carbon park has “no purpose except to keep the oil and gas companies in business.”

The county proposes siting the carbon park near several major oil fields. To recover the large investments necessary for carbon capture, oil producers will need “a significant source of [carbon] — on the scale of millions of metric tons annually — available for injection,” according to a county report for companies and potential investors.

Two oil companies, California Resources Corporation (CRC) and Aera Energy, have applied for federal permits to bury more than a million tons of carbon a year each in the deep underground reservoirs of Kern County. These efforts alone could yield the companies more than $1 billion in tax credits, if federal incentives are renewed in the 2030s. Both support the carbon park idea while planning to continue producing oil and gas.

But to truly combat climate change, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), companies need to quickly phase out oil and gas production. Carbon sequestration plans like the one in Kern County instead provide lifelines to fossil fuel producers, according to climate scientists and policy experts.

Emma De La Rosa, a policy manager for the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, an environmental justice group that opposes the carbon park, called the plan “ludicrous.”

“They’re trying to actually produce more carbon so they can store it,” De La Rosa said.

Since peaking in 1985, oil production has been falling in Kern County, owing to depleted reservoirs. The London-based think tank Carbon Tracker has estimated that oil operators in California will squeeze out most of the last bits of profitable oil over the next two years before a steep decline. That will hammer Kern County, where three-quarters of the state’s oil is produced.

County officials estimate that the park could generate between $28.4 million and $64.1 million in new annual revenue, along with tens of thousands of new jobs. This is in addition to the jobs of oil workers if they are retained or hired to inject carbon into the ground and plug idle wells.

The IEA has said some sequestration is needed to limit emissions from industries like cement and chemical manufacturing that generate carbon in their production process. Even so, the agency recently downplayed the technology’s usefulness, acknowledging that sequestration cannot keep up with the continuing global growth of carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels and deforestation.

Since peaking in 1985, oil production has been falling in Kern County, owing to depleted reservoirs.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Energy provided Kern County with technical assistance to develop a proposal for carbon management. The county appointed an executive steering committee that produced the carbon park proposal.

The committee included officials from local universities that received $2.5 million from CRC to study carbon management, and a representative from the Dolores Huerta Foundation, a civil rights nonprofit that later signed on to a letter opposing the proposal. A representative from the Western States Petroleum Association, which represents the state’s major oil producers, also served on the committee. In June, the county debuted its finished proposal on a new website.

County planner Lorelei Oviatt, who directed the proposal’s creation, declined to be interviewed.

“We are regulators and will ensure any physical project is reviewed under the California Environmental Quality Act and mitigate the environmental impacts associated with all types of clean energy projects,” Oviatt wrote in an email.

Supervisor Zack Scrivner, who introduced a motion for the county to study the idea of carbon management back in February 2020, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Aera Energy did not respond to emailed questions, but sent a month-old press release. CRC and Chevron, another large producer in Kern County, did not respond to questions.

Kern County’s plan misses the point of an energy transition, said Emily Grubert, a professor of sustainable energy policy at the University of Notre Dame. From 2021 to 2022 Grubert oversaw the U.S. Department of Energy’s carbon management program, the same one that provided the technical assistance to Kern. Grubert said she did not provide consultation to the county while she was there.

She does not support Kern County’s plan because it is not focused on phasing out fossil fuels. Instead, it will use renewable energy to keep the oil and gas industry alive. Rather than rely on local plans that will be influenced by area interests, Grubert said the U.S. needs a national plan to phase out fossil fuels.

State officials estimate that direct air carbon capture will require vast amounts of power — the equivalent of three-fourths of the state’s entire grid capacity today.

The carbon park plan proposes an on-site steel mill and a hydrogen production facility. Steel and hydrogen can be produced with newer carbon-free technologies. But the Kern plan puts forth as options both steel mills and hydrogen plants that would generate carbon — the reason for the park’s existence.

Another industry proposed for the site is direct air capture, which pulls carbon out of the atmosphere by filtering air through materials that bond with carbon. The process requires a large amount of electricity. Generating that power could take up a substantial share of California’s renewable electricity capacity.

To meet its goal of capping carbon emissions by 2045, California is building out its electricity generation and delivery. The state plans to use wind and solar power to triple the size of its power grid. That growth will be necessary to power the expansion of green technologies like electric cars.

But state officials estimate that direct air capture will require vast amounts of power — the equivalent of three-fourths of the state’s entire grid capacity today. Critics say it would be better to send that power to the grid while speeding up a phase out of fossil fuels.

The state’s largest oil and gas producers are eyeing direct air capture as a future business. Aera, Chevron, and CRC received $17.6 million from the Department of Energy to develop their own direct air capture projects in Kern County.

They say direct air capture could one day offset the carbon produced by their oil and gas operations — which would continue. But current direct air capture methods are not capable of offsetting that volume of carbon.

Katelyn Roedner Sutter, California director for the Environmental Defense Fund, said that the usefulness of direct air capture is undermined when carbon is still being generated by oil and gas. “If you’re still producing oil and doing direct air capture next door, that’s probably not a climate solution,” Sutter said.