Canada’s new Indo-Pacific strategy, announced with much fanfare by Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly, marks a welcome return of common sense in place of the illusions that have dominated Canada’s approach to Asia for the past quarter-century.

At the same time, there are big gaps that show Canadian policymakers still have a lot of thinking to do.

First off, the strategy strips away the idea of “engagement” with China that Canada pursued under the governments of Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper.

In this policy of wishful thinking, governments of both political stripes aimed to enmesh China in international norms — in other words, standards on how international politics should operate.

Ottawa hoped this would prompt China to become a faithful follower of the “rules-based international order” so beloved of Canadian leaders.

It didn’t happen that way.

Norms are disregarded

Instead, China’s rise was “enabled by the same international rules and norms that it now increasingly disregards,” as the Indo-Pacific strategy paper puts it.

While that’s true, it ignores Canada’s own role. China’s success in changing international norms was actively aided and abetted by Canadians all too keen to get a slice of the vast China trade pie.

Read more: Why did Xi scold Trudeau? Maybe because Canada spent years helping China erode human rights

Still, this belated move towards a less starry-eyed vision of China is welcome. So too is the Indo-Pacific strategy’s plan to reinvest in knowledge about China and the region.

No longer does Canada fund Asian studies as it once did. No longer does it even support studies of Canada in Asia, once a valuable way to build ties of understanding.

The Indo-Pacific strategy also repeats the stale bromides of the past. The strategy leads with breathless gasps about the potential of trade with the vast Asian market.

Entrenched poverty is neglected

There is little change here from the 1990s, when visions of thriving Asian markets danced in policymakers’ heads. No talk, then, of the bears of Asian recessions or the entrenched poverty that showed the problems with the sustainability of the 1990s-era “Asian miracle.”

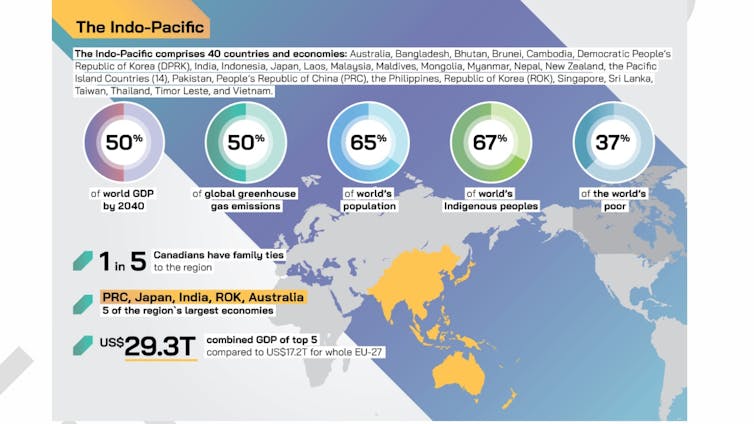

So readers are treated to graphics of Indo-Pacific greatness. One-third of all global economic activity! Half of global GDP! Five economies that together outclass the European Union! This is 1990s rhetoric, recycled almost unchanged for a new century.

Indeed, little is changed from 1970, when Pierre Trudeau travelled to Japan as prime minister and spoke of Asia not as the Far East, but as Canada’s “New West.”

This didn’t mean Mounties would descend to impose law, order and colonialism. It meant that Canada wanted a piece of the trade action. Yet the rhetoric did not lead to much diversification: trade with Japan ticked up slightly in percentage terms, but Canadian trade increasingly flowed southwards to the United States.

What about human rights?

Left almost entirely unmentioned in the new Indo-Pacific strategy: human rights, which have played a key role in Canada-Asia relations for several decades now. Despite Joly’s claims, human rights is not a “key pillar.” The strategy’s five pillars are peace and security, trade, people-to-people exchanges, the environment and more engagement with the region.

Previous international policy statements have at least nodded at human rights. This one relegates rights to a sub-section. There’s no mention, for instance, of Canadians like Huseyin Celil, held unjustly in Chinese prison facilities for almost 20 years.

Read more: A diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Olympic Games could bring Huseyin Celil home

Canada once had a reputation for supporting non-governmental organizations in Asia, funding that flowed through the umbrella description “civil society strengthening.”

The Indo-Pacific strategy speaks of plans to “strengthen dedicated Canadian funding and advocacy to support human rights across the Indo-Pacific, including for women and girls, religious minorities, 2SLGBTQI+ persons and persons with disabilities.”

If this is to succeed, it will need to return to longer-term, sustained support for Asia-based rights organizations.

Building closer ties to democracies

Finally, the strategy speaks of closer ties to Asian democracies such as Japan and South Korea. It also speaks of stepping up ties in Southeast Asia.

Yet there is no mention at all of Southeast Asia’s most functional democracy, Timor-Leste — once a priority country for Canadian support, now largely abandoned by Ottawa.

Read more: Canada's East Timor advocacy 20 years ago paves the way for leadership today

In a little more than 20 years of independence, Timor-Leste has held numerous free and fair elections and raised its low standard of living in the wake of a near-genocide.

Timor-Leste even took on Iran — no paragon of women’s rights, to put it mildly — and beat it for a seat on the board of UN Women, a United Nations organization that advocates for the rights of women and girls around the world.

Read more: Iranian women keep up the pressure for real change – but will broad public support continue?

If ties to democratic regimes in the Indo-Pacific region are to mean anything, Canada must look to smaller, poorer democracies and not only to the obvious trade partners.

It will need to be a rights advocate instead of holding onto old illusions about Asian wealth.

And it will need sustained policy, not a new strategy every few years.

David Webster receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.