In the closing weeks of 1945, months after the Second World War had ended, the Canadian cabinet enacted executive orders to banish more than 10,000 Canadians of Japanese descent to Japan, stripping many of them of Canadian citizenship in the process.

At the same moment that Canada began to turn its attention to the importance of human rights in the post-war world, it contemplated a brazen rights violation at home of enormous scale and cruelty. Canadian history has mostly forgotten about the exile of Japanese Canadians.

Our book Challenging Exile: Japanese Canadians and the Wartime Constitution delves into those dark days.

The end of a crisis often draws less attention than its onset. Dec. 7, 1941 has become, as United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt predicted, a date that lives in infamy.

Japan’s attacks on Hong Kong and Pearl Harbor plunged Canada and the Allies into war in the Pacific. In the months that followed, amid fears that the North American West Coast might become a new front in the Second World War and following decades of entrenched racism in law and policy, Canada ordered the uprooting of every Japanese Canadian from their home in coastal British Columbia.

Rendered stateless, homeless

The uprooting is largely remembered for the internment of more than 22,000 Japanese Canadians in more than a dozen sites scattered across the interior of British Columbia. But that was just the beginning of a cascade of injustice which followed.

Unlike in the U.S., internment did not end in 1945 in Canada. When the Second World War ended, Japanese Canadians had no homes to return to. Years earlier, the Canadian government had made the fateful decision to dispossess uprooted Japanese Canadians of everything they owned, including many of their personal possessions, as well as their businesses, farms and houses.

Dispossession carved the path to exile. As Canada contemplated how to end the internment of a dispossessed people, it settled on scattering and exile. Japanese Canadians would be encouraged to relocate to uncertain lives in eastern Canada or accept banishment to Japan.

To ensure as many Japanese Canadians as possible opted for exile, government officials toured internment camps stressing that rights to voting, the education of children and secure housing or employment would not be assured to Japanese Canadians in post-war Canada.

The policy was devastatingly effective. More than 10,000 Canadians of Japanese descent, all of whom had been uprooted and dispossessed from their homes, signed up for exile in the summer of 1945. When thousands wrote to the government to withdraw those signatures in the months that followed, Canada enacted the orders of exile on the premise that anyone who signed — and their children along with them — were no longer fit to reside in Canada.

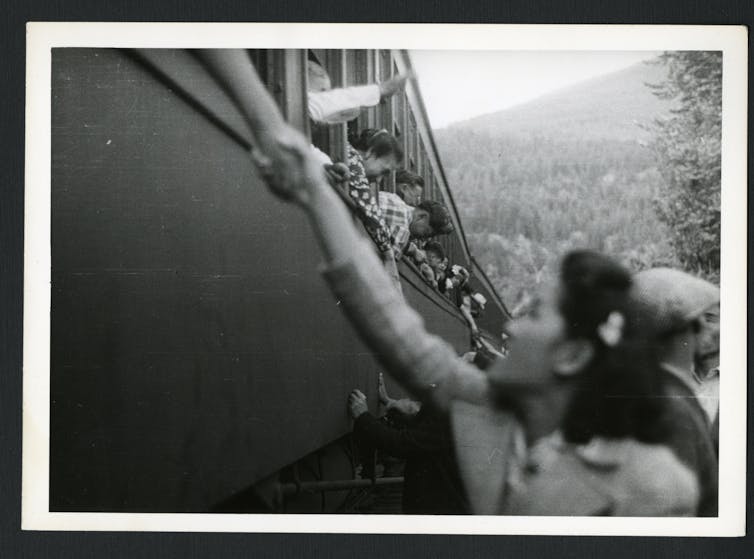

As courts grappled with whether the exile was legal, Canada arranged for the exile of nearly 4,000 Japanese Canadians from May to December 1946. RCMP officers loaded men, women and children onto decommissioned warships and sent them to Japan.

Naturalized citizens were stripped of status, rendered stateless and placeless. Families arrived to a Japan devastated by war and wracked by famine. Many would never set foot in Canada again.

Rationales rooted in racism

Canada’s expulsion of thousands of Japanese Canadians offers lessons in a world of sharpening borders, insecurity and talk of who does and does not belong in a national community.

In the U.S., arguments have resurfaced about denaturalizing citizens, deporting people based on status and about the supposed racial character of citizenship. The same perspectives can be found in the legal and political arguments the governments of Canada and British Columbia employed to justify the exile of Japanese Canadians.

Turning our historical attention to the end of conflict rather than the beginning reminds us of the ways in which harms set in motion in one moment can twist and persist long after the originating crisis has abated.

It reminds us that rationales rooted in racism can become security claims, whether real or imagined. The history of exile should give us pause too about arguments we are hearing again that human rights should never prevent a government from implementing a policy favoured by the majority.

In December 1945, neither courts, legislatures, cabinets nor civil servants stopped the exile of Japanese Canadians. But here too is a final lesson worth remembering.

Although Canada claimed the legal power to exile many more than the 4,000 Canadians it banished to Japan, our book describes how it abandoned the policy when newspapers across Canada began to denounce the policy as fundamentally un-Canadian, anti-democratic and contrary to the equal promise of Canadian citizenship without discrimination.

Fragile rights to citizenship

If Canadian law allowed exile to occur, Japanese Canadians argued, then fundamental Canadian laws needed to change. Eighty years later, the consequences of the exile of Japanese Canadians lingers largely unseen — the trajectories of the lives of thousands of Canadians and the Japanese Canadian community would never be the same.

The Canada that emerged from the exile changed too. It was not that racism or rights abuses disappeared. And yet in the growing movement demanding greater protection for constitutional rights lay recognition of the harms vulnerable communities are exposed to, especially in a moment of insecurity and its aftermath.

On the 80th anniversary of the exile of Japanese Canadians, we should remember the harmful way Canada’s Second World War ended for so many thousands. And we should remember that the fragile rights to citizenship we sometimes take for granted were hard won and emerged, in part as a result of their denial. In that sense, we all live in the shadow cast by exile.

Jordan Stanger-Ross receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. He is affiliated with the University of Victoria.

Eric M. Adams receives funding from SSHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.