As of Jan. 1, 2023, foreign buyers are banned from buying homes in Canada for two years under the Prohibition on the Purchase of Residential Property by Non-Canadians Act. The ban was passed in June 2022, but only came into effect this month.

Under the act, non-citizens, non-permanent residents and foreign commercial enterprises are banned from buying Canadian residential properties. The act also has a $10,000 fine for anyone who knowingly assists a non-Canadian and is convicted of violating it.

The law does not include recreational properties or larger buildings with multiple units. It exempts individuals with temporary work permits, refugee claimants and international students if they meet certain criteria.

It also excludes homes outside of the Census Metropolitan Areas (CMA) or Census Agglomerations (CA). A CMA has a total population of at least 100,000, of which 50,000 or more live in the core area. A CA has a core population of at least 10,000.

The housing crisis

The two-year ban is part of the federal government’s effort to ease Canadians’ struggle to afford homes. According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, the average home price in Canada was above $800,000 in 2022, compared to $500,000 in 2015.

Meanwhile, median after-tax household income in 2020 was $73,000, up from $66,500 in 2015 — a meagre annual growth of two per cent compared to the seven per cent annual growth in average house prices. Canadians were eyeing houses with prices more than 10 times their incomes.

In a recent report published by his think tank, Paul Kershaw, a policy professor at the University of British Columbia, found that average home prices would need to fall $341,000 — half of the 2021 value — to make them affordable for a typical young person at current interest rates. Either that or full-time earnings would need to increase to $108,000 per year — 100 per cent more than current levels.

Who’s the culprit?

Some believe that foreign investors and speculative activities have fuelled Canada’s surging housing prices and spurred the affordability crisis.

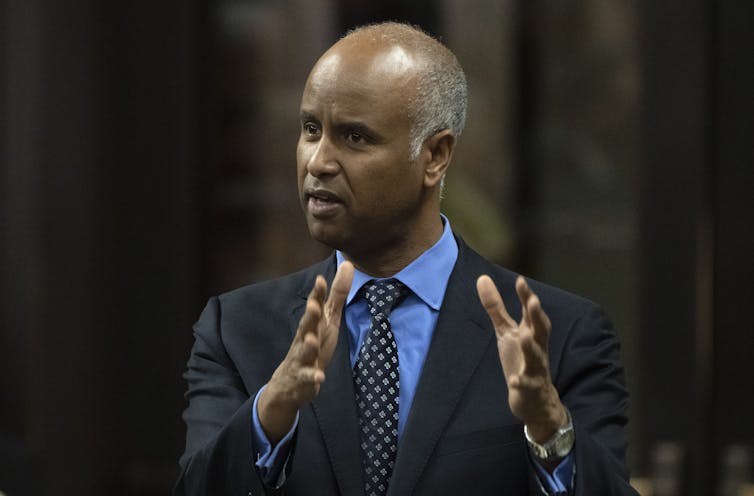

“Homes should not be commodities,” Housing Minister Ahmed Hussen said in a December 2022 news release. He continued:

“Through this legislation, we’re taking action to ensure that housing is owned by Canadians, for the benefit of everyone who lives in this country. We will continue to do whatever we can to ensure that all residents of this country have a home that is affordable and that meets their needs.”

How many foreign homeowners are there in Canada? Data that tracks foreign buyers and owners in Canada are scarce and patchy. The Canadian Housing Statistics Program shows that non-residents only own about two to six per cent of Canadian residential properties in 2020.

The number of foreign participants is scantly relative to the volume of transactions in the market. Foreigners’ contributions to the housing crisis are puny and paltry in comparison with everyone else’s, many of whom have eagerly traded up for bigger homes or down for smaller ones and benefited from the lucrative market.

Is the policy justified?

The law is more of a political gesture than an effective tool. The fact that foreign owners represent a tiny segment of the market suggests the new law is unlikely to exert much impact on making homes more affordable to Canadians.

This gesture, however, does send a signal to Canadians that the government is willing to impose heavy-handed policies to address the housing crisis. The gesture, together with rising interest rates, will cool down the red-hot housing market in the short run.

When a policy aims to push one group into a corner, it is likely to create new challenges elsewhere. Foreigners, for example, can still buy recreational properties in less populated areas. It would be interesting to see if and how the policy might stir up challenges in these exempted areas.

More importantly, the ban is a form of restriction on foreign direct investment in domestic assets and the flow of foreign capital into the housing market. The question is: are we using the policy’s minute impact to justify protectionism?

Encouraging home ownership

The housing crisis is a tricky issue. There is no single policy that could address the affordability issue without introducing other challenges. In fact, most policies would essentially lead one to rethink about what “affordability” actually means.

For one, any housing policies need to achieve a balancing act between two notions of affordability. One notion is based on prices; the other, which tends to receive less attention in the conversation about housing affordability, is about maintaining home ownership status.

Read more: Canada's housing crisis needs answers — but first we need to ask the right questions

Take the recent interest rate hikes as an example. On the one hand, increasing interest rates have lowered house prices to become slightly more affordable to home buyers. On the other hand, the same interest rate hikes have burdened existing homeowners with a heavier mortgage expense alongside other costs in their daily budgets.

Buying a home, and being a homeowner, is not like buying a piece of fine art, which often stays with the owner with little maintenance. Instead, home ownership — a crucial piece of the affordability puzzle — requires people to maintain their cash flow. If we consider affordability from this broader view, it is not surprising to see that the ban is unlikely to affect housing affordability.

Diana Mok does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.