The recent renaming of the Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway in Ottawa to Kichi Zībī Mīkan (“Great River Road”) comes as Canada Day invites Canadians to define not only where we are, but also who we are in our national imagination.

Reclaiming Indigenous names in our public spaces is just one way to create new avenues for what Cree Elder and scholar Willie Ermine calls “ethical spaces of engagement.” This seems in keeping with the mutual respect required to engage in the difficult, ongoing work of reconciliation, the flagship project of which is enacting the 94 calls to action by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC).

As Kanien’kehaka scholar Taiaiake Alfred reminds us in Whose land is it Anyway? A Manual for Decolonization, “it’s all about the land,” meaning that “reconciliation that rearranges political orders, reforms legalities and promotes economics is still colonial” unless and until it centres Indigenous Peoples’ “relationship to the land.”

Canadians are revisiting national self-definition in light of calls for decolonization and reconciliation. In my field of environmental communication, we learn that how we represent a place can reveal much about the place and even more about who we are and what we value.

Space and place

The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan recognized that humans have universal biological, psychological, social and spiritual needs for both space and place.

Non-Indigenous settler Canadians’ connections to the land vary. For example, according to recent statistics, almost one in four people here are immigrants, one in nine Canadians live abroad and one in nine Canadians have multiple citizenships.

For settler Canadians, even if we do stay put, we are by definition removed from our ancestral lands, even if our families have been here for generations. Yet we can be fiercely attached to place, so much so that it becomes a centre for our belonging, behaviour and how we make sense of the world.

In this light, place is more than a location; it also imbues human experiences, emotions and meanings tied to our environment.

Place and collective identity

Environmental psychology suggests place can also become a source of our collective identity. For Canadians, land has become a powerful source of not only attachment but also self-definition, distinction and pride.

This can be constructed and encouraged by culture and media; indeed, the CBC and the National Film Board exist to serve such purposes.

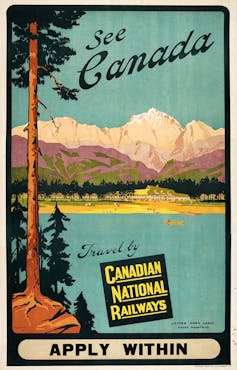

Popular portrayals of Canada have traditionally depicted nature.

Artists like Emily Carr, Gordon Lightfoot and Lucy Maud Montgomery conjured images of landscapes that became emblazoned, in varied ways, in settler Canadians’ national imagination and self-concepts, through their own circulation, additional commentary and the arts, culture and tourism sectors.

Read more: Gordon Lightfoot's music raised awareness of Great Lakes maritime disasters

Place branding

These portrayals matter. Place branding has important implications in the international arena for political influence, trading relationships and more.

Canada’s lauded tourist attractions include natural splendour like Niagara Falls, the Rocky Mountains, Whistler, Baffin Island and Vancouver Island, and new ways of thinking about how to narrate the stories of these places.

Unprecedented interest in Indigenous culture and history shines a spotlight on Canada and its relations with First Peoples.

Depicting place

My study, Tar Wars, illustrated how representations of place have mattered to public understandings of Alberta and Canada in light of their stewardship of the Athabasca tar/oilsands.

That study showed how several independent documentary films, like Dirty Oil and Tipping Point: The Age of the Oil Sands, called out Alberta/Canada for running roughshod over the boreal forest and waters of northern Alberta. These films called attention to the effects the massive extraction project had on the health, well-being and livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples in affected communities.

The oil industry and the Alberta and federal governments responded with PR campaigns asserting their compliance with environmental standards, and the dedication of industry employees.

Read more: Artists organize to offer new visions for tackling climate change

Popular images of Canada’s pristine wilderness were challenged by images of limitless open-pit mines and poisoned water. One viral photo depicted 500 oil-soaked dead ducks. These images fed a perceptible shift in the framing of Alberta/Canada in some popular media, raising questions about who we are and what we value as a nation.

Place as inspiration for action

As the TRC reminds us, reconciliation is an ongoing process of engagement. If settler Canadians value their home, their place and how it’s perceived here and abroad, then we may pause on the nation’s 156th birthday to imagine how diverse Indigenous Peoples, who have been here since time immemorial, might feel about this place sometimes called Canada.

We might choose to take up Ermine’s invitation to create new ethical spaces for engagement.

This could mean drawing on our common attachment to and identification with the land (albeit manifested in different ways) to establish and maintain mutually respectful relationships.

This Canada Day (and every day), creating new ethical spaces for reconciliation seems like a fitting way to celebrate what singer Jully Black noted in her rendition of our national anthem at the 2023 NBA all-star game: our home on Native land.

Geo Takach receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, funded by the Government of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.