Have you ever taken a personality test? If you’re like me, you’ve consulted BuzzFeed and you know exactly which Taylor Swift song “perfectly matches your vibe.”

It might be obvious that internet quizzes are not scientific, but many of the seemingly serious personality tests used to guide educational and career choices are also not supported by research. Despite being a billion-dollar industry, commercial personality testing used by schools and corporations to funnel people into their ideal roles do not predict career success.

Beyond their lack of scientific support, the most popular approaches to understanding personality are problematic because they assume your traits are static – that is, you’re stuck with the personality you’re born with. But modern personality science studies find that traits can and do change over time.

In addition to watching my own personality change over time from messy and lazy to off the charts in conscientiousness, I’m also a personality change researcher and clinical psychologist. My research confirms what I saw in my own development and in my patients: People can intentionally shape the traits they need to be successful in the lives they want. That’s contrary to the popular belief that your personality type places you in a box, dictating that you choose partners, activities and careers according to your traits.

What personality is and isn’t

According to psychologists, personality is your characteristic way of thinking, feeling and behaving.

Are you a person who tends to think about situations in your life more pessimistically, or are you a glass-half-full kind of person?

Do you tend to get angry when someone cuts you off in traffic, or are you more likely to give them the benefit of the doubt – maybe they’re rushing to the hospital?

Do you wait until the last minute to complete tasks, or do you plan ahead?

You can think of personality as a collection of labels that summarize your responses to questions like these. Depending on your answers, you might be labeled as optimistic, empathetic or dependable.

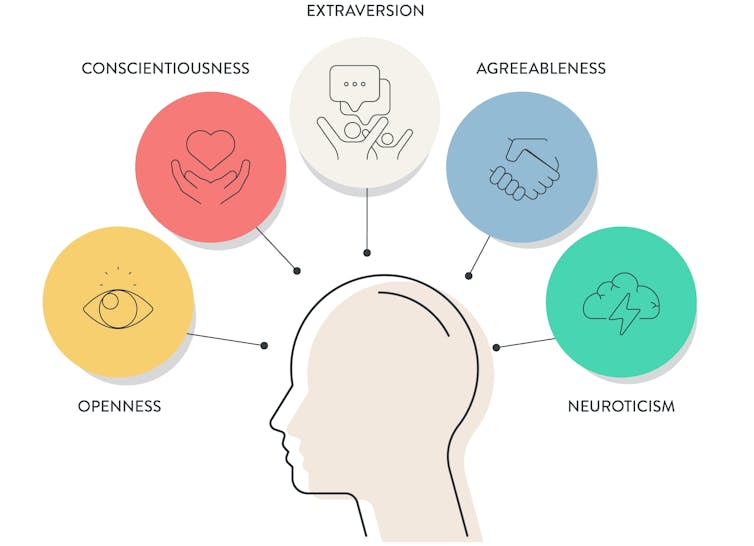

Research suggests that all these descriptive labels can be summarized into five overarching traits – what psychologists creatively refer to as the “Big Five.”

As early as the 1930s, psychologists literally combed through a dictionary to pull out all the words that describe human nature and sorted them in categories with similar themes. For example, they grouped words like “kind,” “thoughtful” and “friendly” together. They found that thousands of words could be accounted for by sorting them between five traits: neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness.

What personality is not: People often feel protective about their personality – you may view it as the core of who you are. According to scientific definitions, however, personality is not your likes, dislikes or preferences. It’s not your sense of humor. It’s not your values or what you think is important in life.

In other words, shifting your Big Five traits does not change the core of who you are. It simply means learning to respond to situations in life with different thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

Can you change your personality?

Can personality change? Remember, personality is a person’s characteristic way of thinking, feeling and behaving. And while it might sound hard to change personality, people change how they think, feel and behave all the time.

Suppose you’re not super dependable. If you start to think “being on time shows others that I respect them,” begin to feel pride when you arrive to brunch before your friends, and engage in new behaviors that increase your timeliness – such as getting up with an alarm, setting appointment reminders and so on – you are embodying the characteristics of a reliable person. If you maintain these changes to your thinking, emotions and behaviors over time – voila! – you are reliable. Personality: changed.

Data confirms this idea. In general, personality changes across a person’s life span. As people age, they tend to experience fewer negative emotions and more positive ones, are more conscientious, place greater emphasis on positive relationships and are less judgmental of others.

There is variability here, though. Some people change a lot and some people hold pretty steady. Moreover, studies, including my own, that test whether personality interventions change traits over time find that people can speed up the process of personality change by making intentional tweaks to their thinking and behavior. These tweaks can lead to meaningful change in less than 20 weeks, instead of 20 years.

Cultivating personality traits that serve you best

The good news is that these cognitive-behavioral techniques are relatively simple, and you don’t need to visit a therapist if that’s not something you’re into.

The first component involves changing your thinking patterns – this is the cognitive piece. You need to become aware of your thoughts to determine whether they’re keeping you stuck acting in line with a particular trait. For example, if you find yourself thinking “people are only looking out for themselves,” you are likely to act defensively around others.

The behavioral component involves becoming aware of your current action tendencies and testing out new responses. If you are defensive around other people, they will probably respond negatively to you. When they withdraw or snap at you, for example, it then confirms your belief that you can’t trust others. By contrast, if you try behaving more openly – perhaps sharing with a co-worker that you’re struggling with a task – you have the opportunity to see whether that changes the way others act toward you.

These cognitive-behavioral strategies are so effective for nudging personality because personality is simply your characteristic way of thinking and behaving. Consistently making changes to your perspective and actions can lead to lasting habits that ultimately result in crafting the personality you desire.

Shannon Sauer-Zavala receives funding from that National Institute of Mental Health to support her research.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.