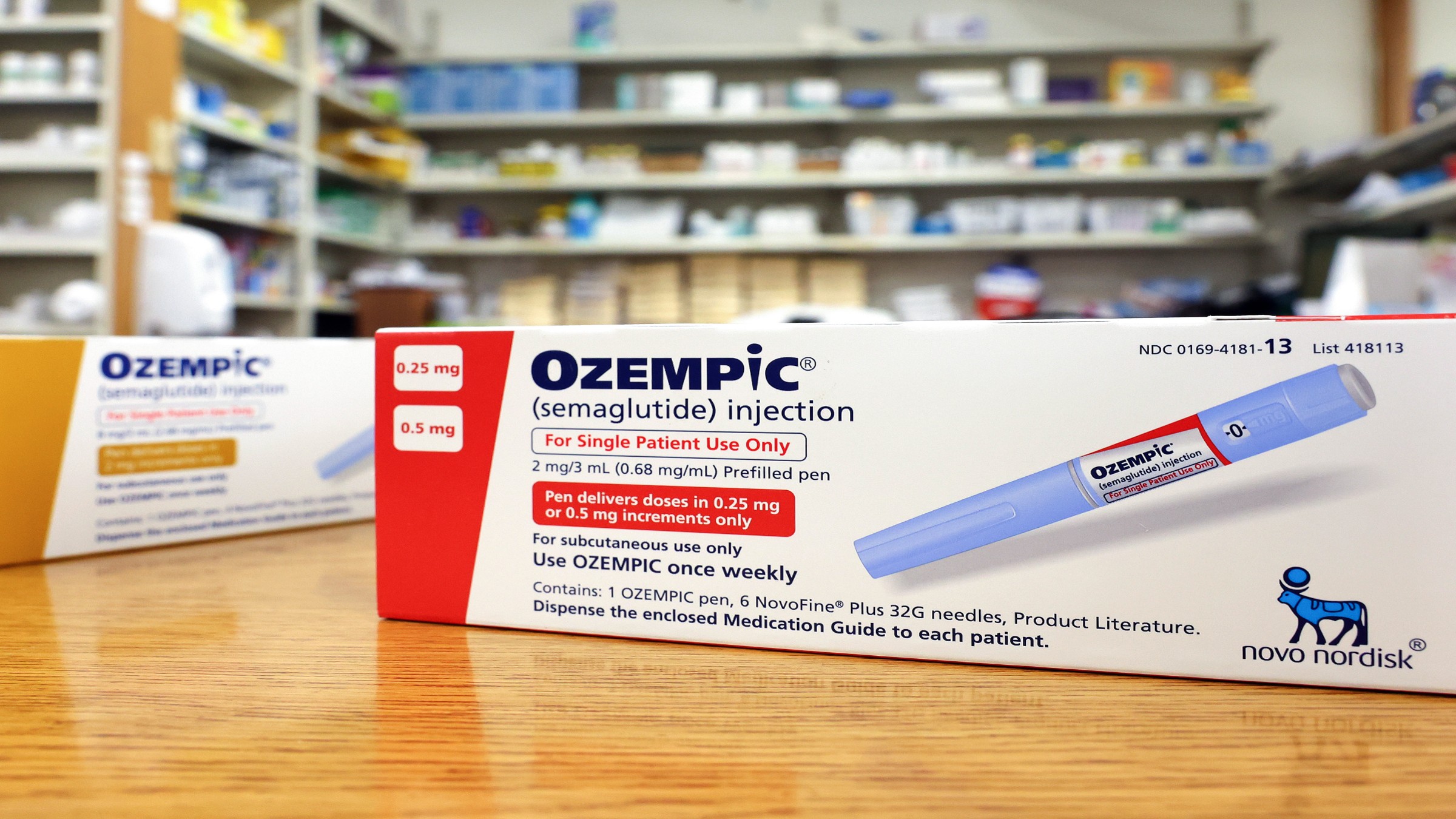

Over the past year, there has been an explosion in the popularity of GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs — namely Ozempic and Wegovy, which are respectively used to treat diabetes and obesity.

However, recent reports, heralded by a CNN story published on July 25, have highlighted several cases of persistent vomiting and "stomach paralysis" in people who take the drugs. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also told CNN that they'd received reports of people experiencing such symptoms after taking semaglutide — the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy — but have not yet determined whether the problems arose from the drug itself or from underlying medical issues.

And in the first case of its kind, a woman in Louisiana has now sued the makers of Ozempic and another GLP-1 agonist, Mounjaro, over claims that the drugs caused her severe gastrointestinal injuries.

So should consumers be worried? And if so, how might these drugs be causing these side effects?

Related: Could Ozempic be used to treat addiction? Studies hint yes, but questions remain

How do GLP-1 agonists work?

To make sense of these anecdotal reports, let's go back to the basics of how these drugs work. GLP-1 receptor agonists mimic the action of a hormone — glucagon-like peptide 1 — that the gut secretes after eating.

GLP-1 has two major roles, Dr. David Levinthal, director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Neurogastroenterology & Motility Center, told Live Science. "One is glucose control, so promoting insulin release and helping reduce blood sugar, and the other is actually programming some of the body's response to a meal, which includes both what the stomach does and what the intestine may do as well."

In the stomach, GLP-1 works almost like a "brake system," essentially slowing down the rate at which the stomach would normally empty food into the small intestine, he said.

Could GLP-1 agonists cause "stomach paralysis"?

According to Levinthal, stomach problems are a known and common side effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic and Wegovy. Most commonly, these stomach issues include nausea and diarrhea.

"Probably a lot of the weight loss [caused by these drugs] is because it actually does impact the stomach's function in a way that probably influences people's appetite, because the stomach isn't emptying very well," Levinthal said. Plus, they interact with parts of the brain that regulate appetite.

Dr. Robert Kushner, a professor of medicine in endocrinology at Northwestern University Feinburg School of Medicine, told Live Science that the way these drugs slow down stomach emptying has been known from "the very beginning of time when these hormones were identified." He explained that patients can expect to experience reduced stomach emptying as their treatment dose is raised to the optimum level, at which point it is crucial that they eat slowly, monitor fat intake and spread meals throughout the day.

Some users may be more likely to experience a greater reduction in stomach emptying as they are already predisposed to this side effect. For example, if they have type 1 diabetes, where high amounts of blood sugar can cause damage to the vagus nerve that normally instructs the stomach to empty food, Kushner said. Patients with type 2 diabetes may also experience similar symptoms, but their risk is lower than that of those with type 1. In a late-stage trial of Ozempic, which included people with type 2 diabetes, most patients who reported gastrointestinal side effects had mild to moderate symptoms which reduced over time.

Typically, patients with severely reduced stomach emptying experience symptoms of vomiting, abdominal pain and feeling full after eating only a small amount of food. Kushner warned, however, that referring to this slow stomach emptying as "paralysis" may cause alarm.

"The medical term [for this condition] is actually gastroparesis, which means slowing of the stomach," he said. The condition is also called gastric stasis, where "statis" refers to a state of inactivity. "Paralysis sounds scary to me, so I can understand why some people would be worried about that."

"In the vast majority of people, this [drug-induced gastroparesis] is readily reversible with decreasing dose or stopping the medication," Dr. Siddharth Singh, a gastroenterologist at UC San Diego Health, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Watch out for Ozempic copycats containing unauthorized active ingredients, FDA warns

What about "cyclic vomiting"?

According to the CNN report, one Ozempic user who'd experienced gastroparesis was also diagnosed with "cyclic vomiting syndrome" (CVS), and reported having to "throw up multiple times a day" even after she stopped taking the drug.

"Cyclic vomiting syndrome is a distinct disorder that looks a lot different than gastroparesis," Levinthal said. "It's an episodic disorder where people are fine almost all the time, and then have an episode of intense nausea and repetitive vomiting." By comparison, the vomiting associated with gastroparesis tends to occur towards the end of meals or just after someone has finished eating a meal.

He emphasized that he'd need to know more about the woman to make a diagnosis but implied the need to be cautious in distinguishing between the two disorders and determining the influence of GLP-1 receptor agonists in both contexts. "It would be very unusual, I think, to link these drugs to that disorder [CVS]," he concluded.

Singh also urged caution about interpreting the reports of vomiting and about being aware of the distinction between typical gastroparesis and CVS.

"There have been rare reports of this [drug-induced gastroparesis] persisting after stopping the medication," he said. "I would not equate this with 'cyclic vomiting' — cyclic by nature implies intermittent or periodic, and I'm not sure if this drug would cause cyclic vomiting."

Related: Woman who spontaneously vomited up to 30 times a day likely had rogue antibodies

So, what should consumers know?

First and foremost, Kushner warned that when starting one of these drugs, patients should ensure that they're under a clinician's supervision.

"It is important that anyone who goes on these medications works closely with the prescriber," he said. People should not attempt to take the drugs by other means, for instance, through being "prescribed by the internet without any guidance or supervision."

Patients should also know the potential side effects, and understand what measures can be taken to mitigate them. This may include reducing dietary fat, not skipping meals and staying hydrated, Kushner said. He added that anyone who experiences any side effects should let their prescriber know as soon as possible.

Levinthal also felt that the fear of potential side effects should not put people off taking the drugs if they could benefit from them.

"It's becoming kind of a cornerstone of treatment for people with gastrointestinal problems — diabetes, and obviously more recently, weight loss, with astounding effect sizes," Levinthal said. "I wouldn't want people to be scared off from even trying the medication in the first place."