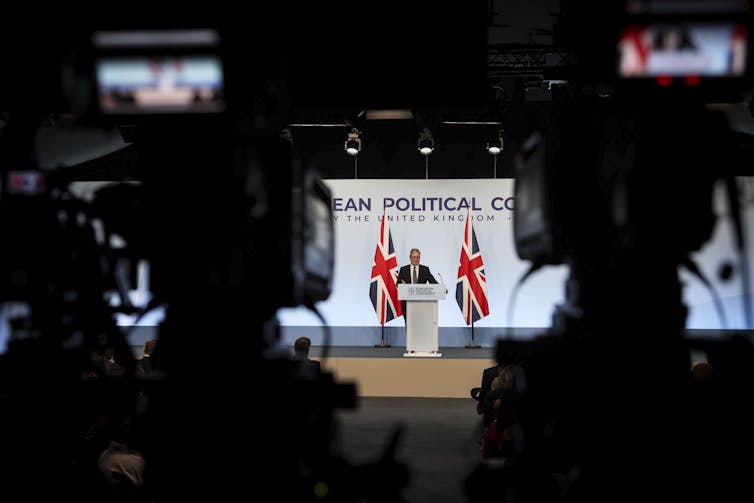

By all accounts, Keir Starmer’s first UK-based foray onto the international stage as prime minister was a success. Last week’s European Political Community gathered nearly 50 heads of government from across Europe to discuss critical issues, ticking all the right boxes in organisation, tone and foreign policy goals.

Initially agreed to by Liz Truss in 2022, Rishi Sunak was lukewarm on hosting the summit. Only a stern warning from Macron about the future of the Anglo-French relations prevented a complete scrapping. Determined to grasp the opportunity, Starmer said it would “fire the starting gun” on a new approach to improved relations with Europe.

The new UK prime minister was emphatic about his desire to replace the knee-jerk, combative style of the previous government with a progressive and collaborative one. He was clear that the UK should be “at the heart” of European efforts on shared problems, including migration and Russian aggression in Ukraine.

To this end, three themes emerged from the day: challenges to democracy (and modes to respond), European security with a particular focus on immigration-related crime and energy security.

These challenges are regarded as insoluble by individual countries or institutions. They require a collective approach through forums like the EPC, and a Europe in which the UK itself asserts “a more active and greater convening role”.

Three key issues of European security

Large summits rarely produce specific solutions to long-term problems. Starmer clearly communicated the UK’s willingness to work more collaboratively with European and EU partners. What this looks like, however, will be in the details – in this case, how the UK and its neighbours approach those three key challenges.

Tackling continent-wide challenges to democracy will require more than a mere dedication to “upholding democratic values and international law”. Though, it is reassuring to see this aim outlined in print in communiques from the PM’s office, and clarified in previous and current examples of the UK’s foreign policy stance under David Lammy.

More practical were suggestions on tackling crime associated with irregular migration. The UK’s border security plans (with a focus on counter terrorism-style powers to disrupt organised immigration crime) require close collaboration with Europe.

Here, Starmer had to walk a fine line between EU perceptions that the cross-Channel small boats issue is specific only to the UK, and demonstrate that irregular immigration is a growing challenge for all of Europe. He emphasised that irregular immigration is connected to European security more broadly, and identified both UK and European methods of dismantling smuggling rings and routes.

European security, however, means more than just border and immigration issues. The summit gave Starmer a chance to test the waters on his government’s proposed foreign policy and security pact with the EU.

This could, in Europe’s view (espoused by the likes of David McAllister MEP and French president Emmanuel Macron) cover a range of issues. Economic, climate, health, cyber and energy security were all outlined in April by Lammy himself as part of his “progressive realism” approach to the UK’s foreign policy.

The last area, energy security, was tied into overarching challenges arising from the volatility in Ukraine, as well as security of supply issues, price spikes and climate change.

The value of the EPC

Starmer pulled off a successful summit of European leaders with little time to prepare. Still, he was credibly able to reset both the role and commitment of the UK within Europe, overall, and with key EU partners, in particular.

He also gave credibility to the role of the EPC itself as a useful mechanism, not only to restore UK-Europe relations, but to keep the EU itself alive and kicking. Past meetings of the EPC have been controversial among some European leaders, and beset by arguments over the agenda. Starmer’s supportive approach is a boost to the EPC as a novel European diplomatic format, possibly even one that can help “develop Europe’s sovereignty”.

This suggests that the EPC’s loose structure has intrinsic use: from its themed working groups, to its myriad bilateral meetings (both planned and unplanned), devoting time to solving problems rather than the platitudes of end-of-summit communiques.

Taken together, the EPC appears to be taking hold as a novel form of “European governance lite”. Whether the issues raised can be solved in detail in the longer term within EU and non-EU formats remains to be seen.

What also sets this forum apart from others is the host’s ability to invite guests. From Ukraine’s President Zelensky to Nato, the OSCE and the Council of Europe, Starmer had a singularly timely opportunity to lay the groundwork for other, improved global relations and to take a lead role in a European defence strategy, as America’s commitment potentially weakens.

The next EPC summit will take place in Hungary in November. Six months is long enough to make some progress on the key themes (and for Starmer to solidify bilateral relationships with key neighbours including France).

But it may prove to be the most challenging summit so far. Given Viktor Orban’s opposition to backing Ukraine against Russian aggression, the backdrop of unquestioned support for Ukraine could be tense at best and unworkable at worst. And, given that the summit will take place a mere two days after the US election, impending volatility in transatlantic relations could redefine the entire agenda.

Professor Amelia Hadfield has previously received Erasmus+ funding from the European Commission.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.