Even for former U.S. President Donald Trump, a master at attention-getting, trying to counterprogram during the Democratic National Convention is nearly impossible.

When one party’s members and supporters gather for their biggest party every four years, the other party routinely endures a week of being largely ignored, no matter how creative or dramatic its own counterprogramming efforts may be.

That doesn’t mean that opposing party campaigns should go on vacation during convention week. They can and do make their case regarding the upcoming election while the other party honors its nominees.

But with all the reporters and public attention focused on the convention, these four-day gatherings are far from optimal times for the opposing party to be heard.

The typically one-sided media attention of convention weeks is part of the reason that political campaigns usually see a post-convention bounce of a few percentage points. But the impact of conventions on public opinion used to be much greater in the past, when there was less political polarization.

Convention bounce

In 1992, for instance, Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton was a single percentage point behind incumbent GOP President George H.W. Bush when the Democratic convention started. After the convention, Clinton was up by 29 points.

In 2000, GOP candidate George W. Bush saw an 8-point gain over Democratic rival Al Gore after the 2000 Republican convention.

But those bounces are often short-lived.

As I discuss in my book Presidential Communication and Character,“ even those huge bounces in 1992 and 2000 gave way to much closer elections.

More recently, the only candidate who enjoyed a post-convention polling gain of more than 4 points was 2008 Republican nominee John McCain. He went on to lose to the Democratic nominee, Barack Obama.

Few openings for political attacks

The best an opposing party can hope for during convention week is a convention misfire.

The trouble is, such debacles rarely happen in an era where the presidential selection process is usually absent any last-minute drama. Designed to minimize controversy, the conventions themselves have become ever more scripted.

That wasn’t always the case.

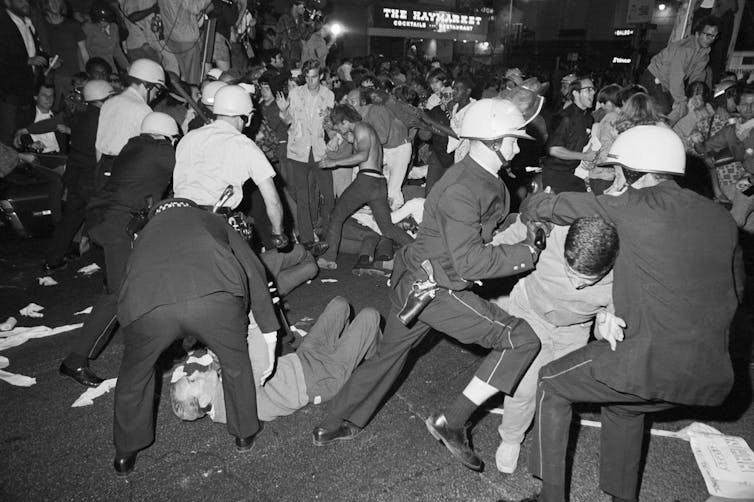

The tumultuous Democratic convention of 1968 created lots of opportunities for Republicans to draw attention to the chaotic scene in Chicago – and, by extension, the chaos within the Democratic Party. But they didn’t need to do so, because the nationally televised images of Chicago riot police using tear gas and billy clubs to subdue anti-Vietnam War demonstrators spoke for themselves.

Troubled vice-presidential selections, like Democrat Tom Eagleton in 1972 and Republican Sarah Palin in 2008, can also trigger sustained partisan responses as Democrats quickly launched after Trump selected JD Vance, an Ohio U.S. Senator, as his running mate.

Those partisan attacks usually intensify in the days and weeks after the convention, particularly if the running mate struggles to find their footing on the national stage.

Trump’s playbook

In the days leading up to the Democratic convention, Republican officials emphasized Democratic divisions over Israel’s war in the Gaza Strip. GOP leaders also have tried to capitalize on potential discontent over how Vice President Kamala Harris became the party’s nominee without having to go through a primary, a process that Trump has called a "coup.”

The Trump campaign has tried to paint Harris and her running mate, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, as a communist or pro-China and has falsely argued that images of enthusiastic Democratic crowds cheering on the ticket were generated by artificial intelligence.

Even though some Republicans encouraged Trump to spend less time talking about conspiracies and making character attacks against Harris, Trump is drawn to his own strategy. Instead of heeding their advice, Trump has continued his personal attacks against Harris, subsequently calling her father, a Stanford University economics professor, “a Marxist.”

So far, though, the 2024 Democratic Convention doesn’t look at all like 1968. The comparatively small number of protesters inside and outside the convention hall has not given the Republican counterprogramming team much to exploit.

Not easy for Democrats, either

Earlier this summer, Democratic efforts at counterprogramming during the Republican convention also fell flat.

The limited media attention Democrats received during Trump’s renomination week focused almost exclusively on the question of whether President Joe Biden would abandon his reelection bid – not the preferred topic of the party’s counterprogrammers.

In addition, Biden’s timing demonstrated the challenges of shaping the narrative during opposing party conventions.

By Biden making his announcement that he was leaving the race three days after the Republican convention ended on July 18, Harris’ campaign launch did not have to compete with Republican convention news.

Conventions last less than a week, and campaigns go on for months. Absent any major misfires, counterprogramming efforts this year – like so many convention years before them – won’t be remembered for long.

Stephen J. Farnsworth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.