A Cambridge college spent £120,000 attempting to remove a memorial linked to the slave trade from its chapel.

Jesus College fought the Church of England in a consistory court case in February to remove the memorial to an alternative space but ultimately lost the case.

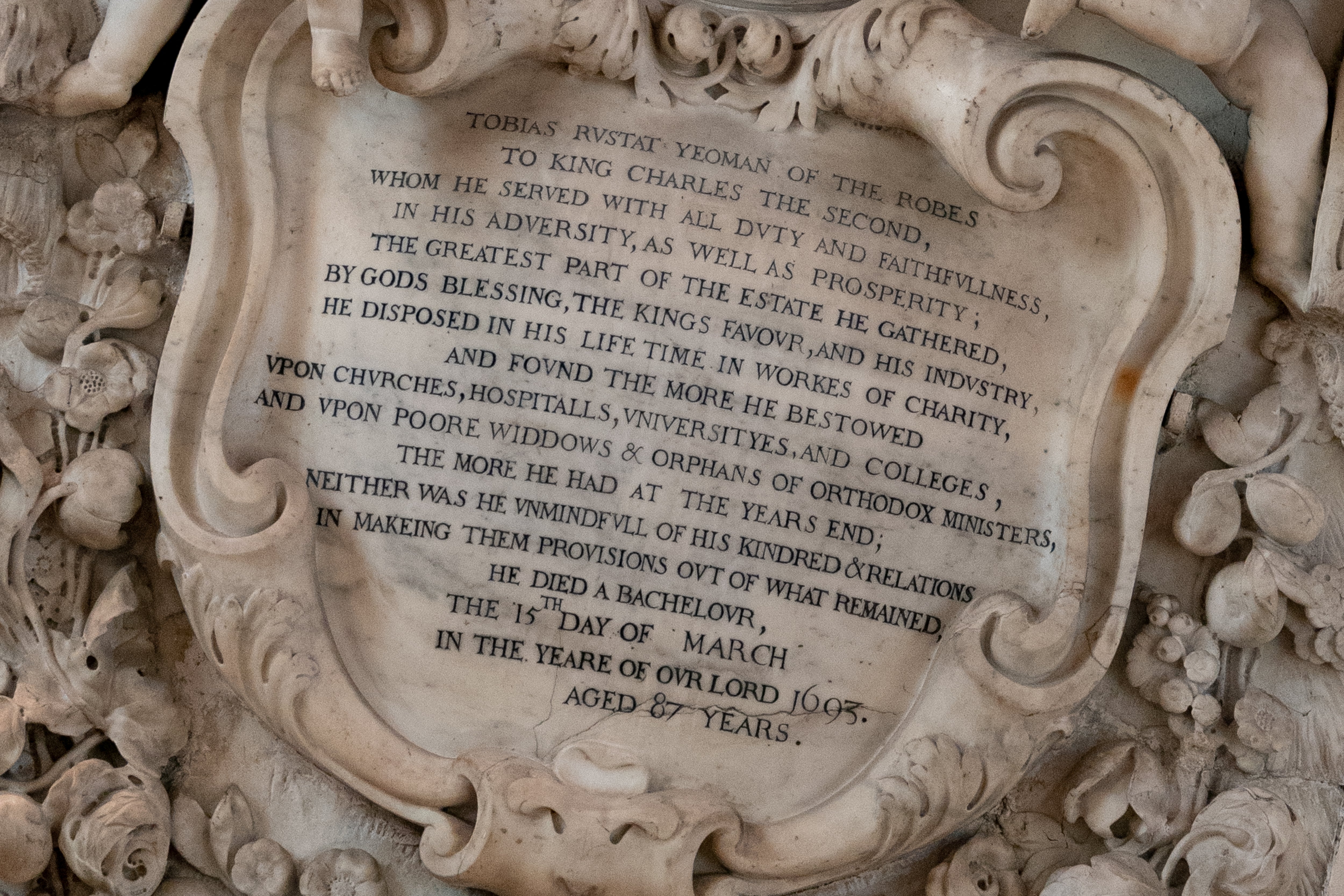

The plaque commemorates Tobias Rustat, a benefactor of the college who invested in the slave trade for three decades.

The college will have spent about £120,000 on an antiquated process that it had little choice but to follow

But in March, the Diocese of Ely decided it would not be removed, claiming that the campaign to move the plaque had been based on a “false narrative” that “Rustat had amassed much of his wealth from the slave trade”.

Jesus College has said this argument is “irrelevant” and what matters is Rustat’s active involvement in the trade.

Sonita Alleyne, Master of Jesus College, writing in The Guardian, said that in 2019, before she was elected Master, the college had set up a working party on the legacy of slavery.

“Our rigorous investigation uncovered much about individuals and objects historically linked to the college,” she said.

“And as a community we asked: what should we do with this knowledge, with this truth, in relation to wider issues of fairness today?”

Ms Alleyne said that in November 2021 the college had returned a looted Benin bronze to Nigeria, and that the working party’s work had also highlighted the history of a plaque commemorating Tobias Rustat in the college chape. Rustat was a seventeenth century investor in the slave trade.

She said a majority of college fellows had wished to remove the plaque from the chapel to an alternative exhibition space, adding that this felt “straightforward” from a moral point of view.

“Rustat’s activities helped finance the slave factories along the west African coast,” she said.

“This enabled ships to transport tens of thousands of enslaved women, children and men across the Middle Passage.

“And it led to these people being worked to death in the killing fields of the Caribbean and Americas.”

She added that moving the plaque also felt straightforward for practical reasons, because it had been moved on a number of occasions throughout the college’s history.

But Ms Alleyne noted that the Church of England had taken a different view after the college lost the ecclesiastical court case as part of its bid to remove the plaque.

She said that “what should have been a simple decision turned into a convoluted consistory court process”.

An increasing number of students would no longer enter the chapel to pray, reflect, or listen to the choir, Ms Alleyne said.

Why is it so much agony to remove a memorial to slavery

“The college will have spent about £120,000 on an antiquated process that it had little choice but to follow, dominated by lawyers, and which is ill-designed for resolving sensitive matters of racial justice and contested heritage,” she said.

“The church must develop something better than this.”

She said that the process “was incapable of accounting for the lived experience of people of colour in Britain today”.

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby has said he supports the plaque’s removal, asking: “Why is it so much agony to remove a memorial to slavery?”