Seventy-five years ago, Hollywood delivered a valentine to Chicago journalism with the ripped-from-the-headlines film “Call Northside 777.”

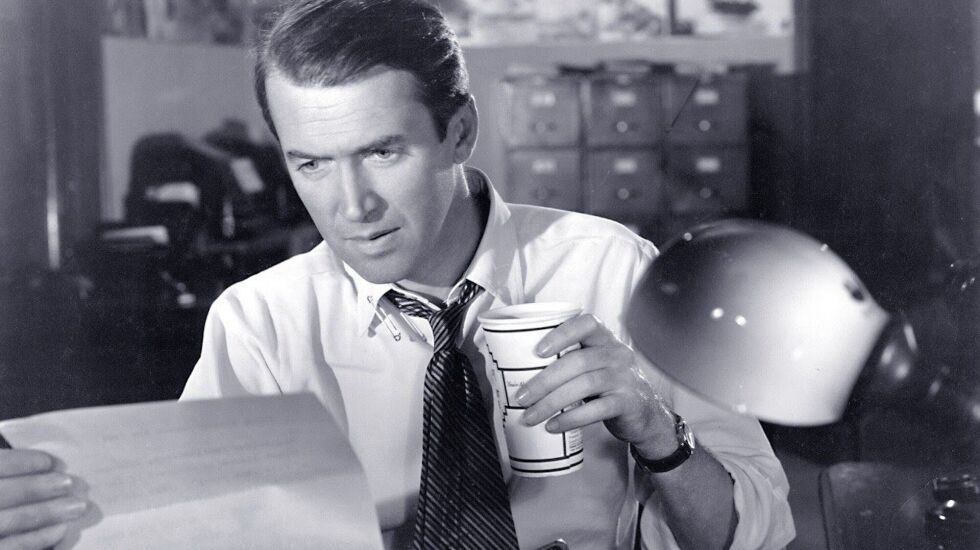

Based on a real-life murder that led to a wrongful conviction in 1933, the movie stars Golden Age movie icon James Stewart as a reporter who revives a cold case for the Chicago Times — which in 1948, after a merger, became the Chicago Sun-Times.

“Call Northside 777” (1948) also played a significant role in Chicago cinema history. Filmed in the fall of 1947 for 20th Century Fox, it was the first Hollywood production to be shot on location in Chicago, with stops at landmark locales including the Wrigley Building, the Merchandise Mart and Holy Trinity Church, as well as Schaller’s Pump, a historic bar at 3714 S. Halsted St. that closed in 2017 after a 136-year run at its Bridgeport locale.

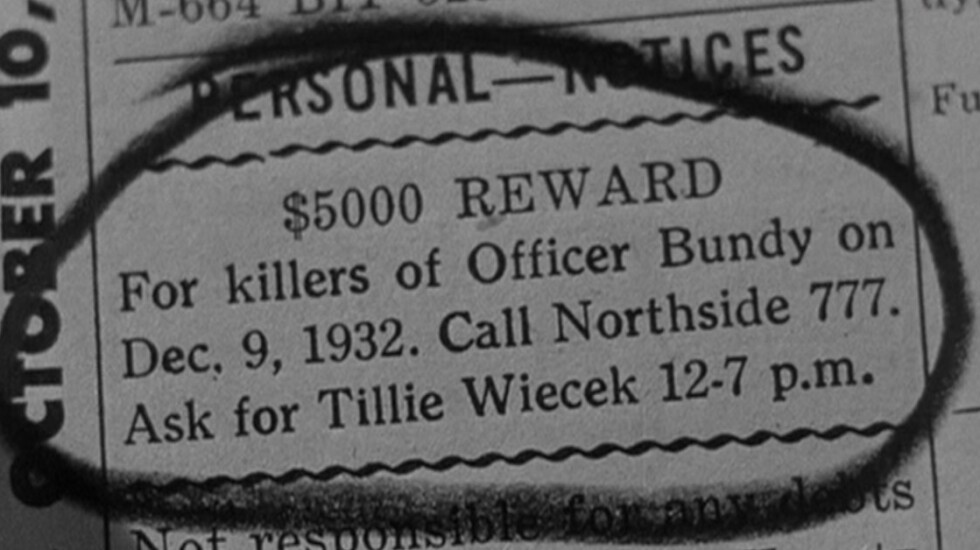

The case centered on the conviction of Joseph Majczek and an accomplice on charges of killing a police officer in a Chicago speakeasy. After saving $5,000 — which would be about $86,000 in today’s dollars — over 11 years, Majczek’s mother, a Polish scrubwoman, placed a personal notice in the Chicago Times. As depicted in the movie, that ad read: “$5,000 Reward: For killers of Officer Bundy on Dec. 9, 1932. Call Northside 777.”

“Call Northside 777” will be screened at 6:45 p.m. Aug. 26 as part of the annual Noir City Chicago, a festival of 18 films running Aug. 25-31 at the Music Box Theatre. Presented by the San Francisco-based Film Noir Foundation, Noir City is programmed by Eddie Muller, the foundation’s founder and Turner Classic Movies host who’s also emcee of TCM’s weekly “Noir Alley” showcase, and Alan K. Rode, an author, film historian and Film Noir Foundation board member.

“I love newspaper movies in general, and ‘Northside’ is a great one,” said Muller, whose father was a longtime sportswriter for the San Francisco Examiner.

Newspaper ink flows freely throughout this edition of Noir City. “Northside” is one of three journalism-themed movies in the lineup, along with “Chicago Deadline” (1949) and “The Big Clock” (1948).

Both Muller and Rode acknowledge that “Call Northside 777” is sort of a ringer. With its mix of gritty realism and hard-boiled drama, it’s what they like to call “noir-stained.”

“It’s a documentary-style noir,” Rode said. “It came out of the era of [the newsreel serial] ‘March of Time’ documentaries. ‘Northside’ has a good script and a director in Henry Hathaway, and it turned out to be very successful.”

Dozens of cold-case TV series have sprung up since the late 1990s, but films like “Northside” helped to set the template for the genre.

This case had it all: a shady defense lawyer, a politically compromised judge and a deceptive key witness trying to hide her role as a speakeasy operator.

“The assumption was that the city of Chicago bungled the prosecution because it was busy with the World’s Fair,” Rode said. “They blew this case. It was topical and perfect grist for [Fox chief Darryl F.] Zanuck.”

To streamline the story, characters were renamed or combined. Majczek is Frank Wiecek (Richard Conte) in the movie. Reporter James McGuire and Times rewrite man John J. McPhaul became P.J. McNeal (Stewart).

Sandwiched between the transitional films “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946) and “Rope” (1948), in which Stewart broke away from his previous “aw-shucks” image, “Northside” features one of his best performances.

“It’s a different Jimmy Stewart, a tougher one,” Muller said, “in a part that paves the way for his antihero roles in the ’50s,” especially the signature dark Westerns by Anthony Mann.

Muller considers Hathaway, nicknamed “Hollering Hank” for his despotic behavior on the set, very underrated.

“He gets lost in the shuffle because he’s not a myth-maker like [John] Ford or [Howard] Hawks,” Muller said. “He’s a craftsman and adapts to the material. He doesn’t have a signature style. In the ’50s, he became the poor man’s Anthony Mann.”

For their efforts in helping to free Majczek in 1945, the Times reporters received the Heywood Broun Memorial Award, which honors work in the spirit of that crusading journalist. The National Headliners Club bestowed the Times with its “Outstanding Public Service Award.” And the state of Illinois granted $24,000 to Majczek for his wrongful conviction.

But the story didn’t end there. A state legislator, in a typical Illinois-style move, tried to extort $5,000 from Majczek after his release. Once again, the newspaper came to the rescue. A series of articles about the shakedown prompted a grand-jury investigation, righted another wrong — and confirmed the power of the press.