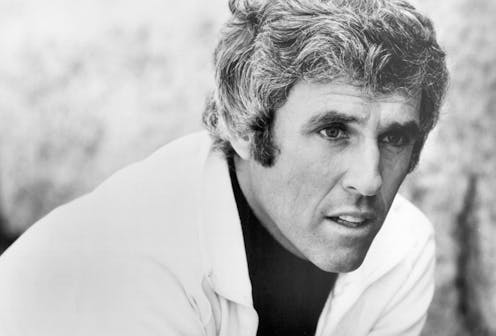

Easy on the ear, perhaps. But the label of “easy listening” often attached to the songs of Burt Bacharach belies the mastery of his talent in crafting perfect moments in music.

Yes, Bacharach’s back catalog is filled with memorable, catchy melodies – whether they were written with longtime partner and lyricist Hal David, former wife Carole Bayer Sager or in collaboration with more contemporary artists such as Elvis Costello, Adele and Dr. Dre.

But there is a harmonic and rhythmic complexity to his music that elevates it above the sweet, often saccharine arrangements that can typify easy listening. It is full of influences from jazz chord structures and progressions, as well as rhythms.

It is why Bacharach, who died on Feb. 8, 2023, at the age of 94, appealed to generations of listeners, as well as the diverse pool of singers who chose to work with him.

Cross-generational appeal

Bacharach began his long songwriting career in the 1950s, but it was the following decade that saw him come to prominence with a series of hit songs.

But with the 1960s as a backdrop – a time of immense innovation in popular music – Bacharach may not have been taken as seriously as many of his contemporaries. It was a time when rock ‘n’ roll and the British Invasion were at the forefront, with rhythm and blues, protest music and folk rock finding their way on the musical landscape.

While Bacharach’s musical counterparts were writing and performing music that responded to and reflected the political, social and cultural upheavals that defined the era, Bacharach and David’s songs focused on different themes: Theirs was music that dealt with relationships and matters of the heart.

They also stood apart from other notable songwriting partners of the age – Lennon and McCartney, Jagger and Richards, for example – in that the songs were written for others to perform. In that way, they were a throwback to an earlier age of popular music, when the likes of Rodgers and Hart provided hit after hit for a roster of singers.

Indeed, they were a late product of Tin Pan Alley – the music industry centered around midtown Manhattan. Bacharach met David in 1957 in the storied Brill Building in New York City – a place where a young songwriter could perhaps catch a break.

Not long after they began working together, Bacharach came across a young backup singer at a recording session who seemed to have promise. The first single he produced with her, “Don’t Make Me Over,” was the first of 38 songs he and David produced with Dionne Warwick.

Her warm tones and fluid phrasing made Warwick’s voice the perfect accompaniment to Bacharach’s music.

But she was one of many collaborators. Some, like Warwick, were plucked from relative obscurity. Others, like Perry Como, were already established singers.

The list of artists who found success with Bacharach songs in that era is astonishing: Aretha Franklin, The Carpenters, Dusty Springfield, Tom Jones and The 5th Dimension, to name just a few.

Through collaborators, Bacharach’s music was able to reach a fairly diverse audience. The songs were so well written that they could easily be reworked into different genres, and break the confines of “easy listening” – a genre often maligned as unhip. In the hands of Isaac Hayes, the sweet refrains of “Walk on By” becomes a psychedelic funk classic. Years later, The White Stripes transformed “I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself” into a stripped-down, guitar-heavy slice of rock.

Froms Oscars to revivals

The music of David and Bacharach also worked on a different level – as the background to movie soundtracks. The 1966 Michael Caine film “Alfie” is perhaps equally known today for the title track, with versions by Cher, Warwick and British singer Cilla Black all becoming hits on the back of the film.

In 1969, Bacharach and David’s “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” sung by B.J. Thomas in the western “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” won the Academy Award for best original song. Bacharach also won the Oscar for best original score.

Adding to success on the charts and on screen, Bacharach also won acclaim for his work on Broadway. The 1968 show “Promises, Promises” was groundbreaking in its use of amplification in the orchestra, which included a rock band. The show contained a number of songs that topped the charts, most notably Warwick’s version of the show-stopping “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again.”

In an NPR “Fresh Air” interview in 2010 – when the musical was being revived on Broadway – Bacharach discusses the number of rhythmic meter changes in the title song, “Promises, Promises,” and the difficulties these rhythmic changes presented for singers and musicians in the show.

The interview is also notable in that it reunited him with David – the two had a much publicized split in 1973 after working on a failed movie. The breakdown of their successful musical partnership saw Bacharach lose interest in writing music for a spell, and affected his relationship with Warwick.

This was eventually resolved with her recording of one of Bacharach’s most memorable songs, 1985’s “That’s What Friends are For,” written with his then-wife, Carole Bayer Sager. Though the song had been first recorded by Rod Stewart for the film “Night Shift,” the Warwick & Friends’ version – the friends being none other than Elton John, Gladys Knight and Stevie Wonder – is the one that became a hit and helped revive Bacharach’s career.

Though best known for the songs he wrote in the 1960s through the 1980s, Bacharach continued to write music into his old age, collaborating with Elvis Costello, Adele and Dr. Dre.

You may have noticed the sheer number – and range – of artists Bacharach worked with. It speaks to the quality and endurance of his output. Yes, he will be remembered by some as the writer of exemplary “easy listening” songs. But Burt Bacharach’s legacy will prove that he was so much more.

Gena R. Greher does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.