Happy Days Lyttelton, London SE1

The Vortex Royal Exchange, Manchester

In a large leap of imagination, Deborah Warner and Fiona Shaw have made an epic out of a miniature. Everything about Warner's production of Happy Days is big: the physical scale, the suggestion of global catastrophe and, above all, Shaw's performance. Beckett's play (one of his best) is more often seen as small-scale and inward, but it can withstand this radical presentation, which claims a woman's place is at the centre of the universe; no drama has made a better case for seeing a world in a grain of sand.

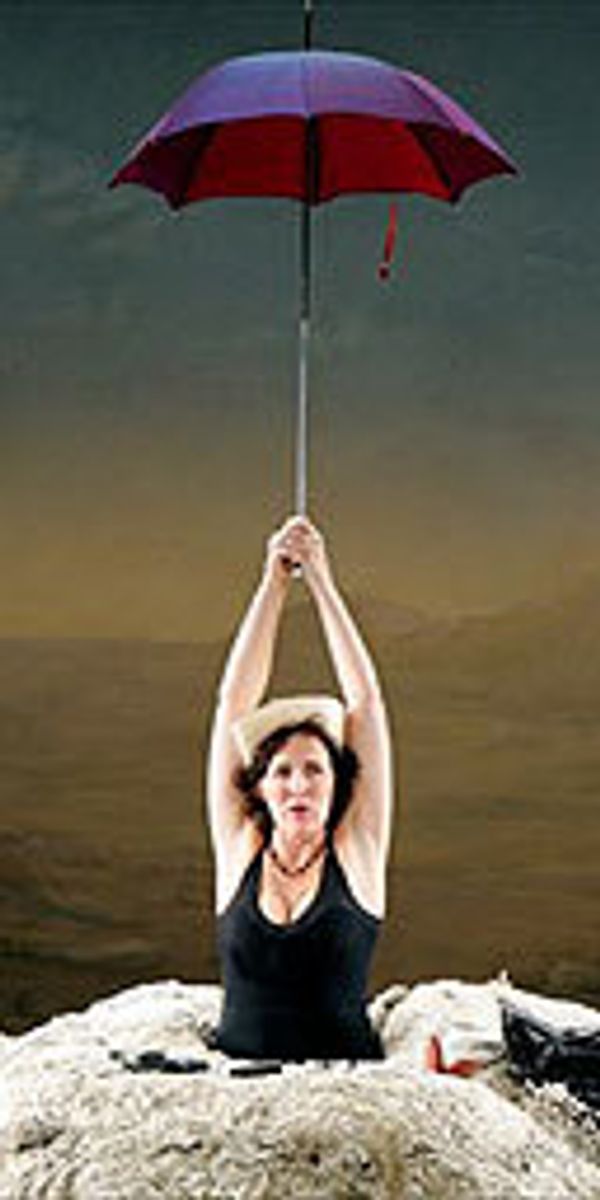

Happy Days has long been an emblem of the avant-garde; a near-monologue and a taxing feat of memory, in which Winnie, buried to her waist in earth, is diverted mainly by her handbag, parasol and a passing ant. Out of sight for most of the non-action, her husband Willie grovels around, alternately disdained and patronised: 'It's not easy crawling backwards, but it is rewarding in the end,' Winnie coos to him.

Tom Pye's design is an apocalyptic ruin: Winnie pokes out of a giant heap of rubble; behind her, a desert stretches to infinity. When her parasol goes up in flames, it is no mere sizzle, no music hall joke, but a fireball that whizzes from above as if a nuclear weapon were being tested.

Shaw finds a way of rising to this which suits her febrile style. This Winnie is herself an actor, who, with all physical gesture constrained, has to talk herself into life ('Life,' she muses, 'I suppose there is no other word.') She begins in artificial gaiety; shaking her locks out of her Panama hat, emitting high-pitch squeals of laughter, humming (not a good idea) the theme tune of The Archers. Behind her, Tim Potter's apt, croaky Willie, leaking unwelcome fluids from every orifice, begins to look like some dreadful part of her own body that she's forgotten.

What she does in the second half is still more remarkable. With the landscape risen round her chin like a surgical collar, she has aged terribly: her cheeks are sunken, teeth are missing (that one tube of toothpaste, with the ingredients that she has marvelled over, never was going to last a lifetime). When she finally sings her song (very important, she keeps pointing out, not to warble until the right moment), her voice is squelchy, distorted, as if her throat were being squeezed to death.

A quarter of a century before Beckett, Noel Coward was causing uproar with The Vortex. The Lord Chamberlain tried to stop the play on the grounds that it gave 'a wholly false impression of Society life' (as if Society lifers didn't give false impressions all the time). Theatrical grandee Gerald du Maurier confusingly boomed that 'the younger generation are knocking at the door of the dustbin'. Coward, whose name was made by the fuss, pointed out that the play was extremely moralistic. Actually, it's obtrusively so.

Jo Coombes's lively revival, in a black-and-white whirligig design by Lez Brotherston, has frisson casting. Coward originally took the part of a young musician, petted son of a giddy society hostess, who returns damaged, and drug-addicted, from debauchery in Paris (Coward's patriotism presumably obliged him to show that the infection wasn't home-grown).

Now Will Young, who knows what it is be a musical talent and to be Idolised, takes the role. He's graceful and likable and easily puts across adorability. But he doesn't have the effortlessness on stage that he's shown on screen - he was the surprise talent in Mrs Henderson Presents. His wheeze for showing he's not all he seems is to become startlingly camp: he flounces, pouts and floppy-limbs across the stage, which makes sense of his over-closeness to his mother, but makes the announcement of his engagement risible.

Three female actors give him strong support. Laura Rees makes a nicely beady fiancee. As the mother, Diana Hardcastle immaculately captures fading glory and avidity. In the part of the truth-telling friend, who is herself not all she seems (she casts a more than friendly eye in the direction of her hostess), Alexandra Mathie manages to upstage even her black silk pyjamas, the best nightwear ever to slink across the boards.