The British vote to leave the European Union in 2016 sent a shockwave across the European continent. With a large member state turning its back on the union, it seemed eminently possible that others could follow.

But when the UK was plunged into economic and political turmoil by its decision, however, it seemed that Brexit had set an unappealing precedent. European leaders had feared a potential surge in eurosceptic movements in their own countries but that did not fully materialise.

Now the EU appears to be enjoying a longer-term Brexit dividend. The decade before the Brexit vote had been characterised by political paralysis. Member states appeared divided on how to manage the fallout from the eurozone crisis and the rapid influx of refugees from Syria as well as other migrants in 2015. This led to a slump in public support for the EU.

While the benefits of EU membership are difficult to quantify or observe for ordinary citizens, the UK’s departure provided clear benchmark for public opinion in the remaining 27 member states about the costs and benefits of leaving.

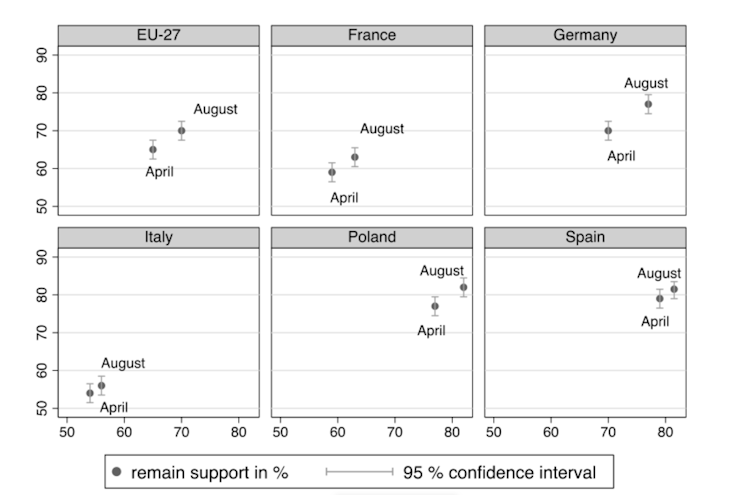

I examined whether people’s opinions about the EU changed via two waves of eupinions surveys conducted by my colleagues and I together with the Germany-based think-tank the Bertelsmann Foundation. The data I rely on here is from April 2016 (just before the Brexit vote) and August 2016 (just after). Respondents were asked if they would vote to remain in or leave the EU if a referendum were held today.

Support for remaining in the EU April and August 2016

Overall, support for remaining in the EU was slightly higher in August 2016 than it had been in April, prior to the Brexit vote. The biggest jump in support for remaining in the EU was recorded in Germany.

Support for remaining in the EU was overall quite high, anyway, at an average of about 70% across EU member states. But looking at individual member states, differences become more evident. In Germany, Poland and Spain, support rested at or topped 70% before the Brexit vote and climbed even higher in the months that followed it – in Poland and Spain to higher than 80%. While France and Italy also saw a rise after the vote, any change happened at a much lower baseline. In fact, in Italy support for remaining inside the EU hovered between the 50 and 55% mark.

The years after the referendum

Of course, many things have happened in the years since the 2016 referendum – from the COVID pandemic to the war in Ukraine. But generally these events, like Brexit, are associated with increased positivity towards remaining within the EU.

The years following Brexit were characterised by a desire to work together. The various crises had the potential to remind the public in the remaining 27 member states of the raison d’être of the EU and boost support for European project as a result.

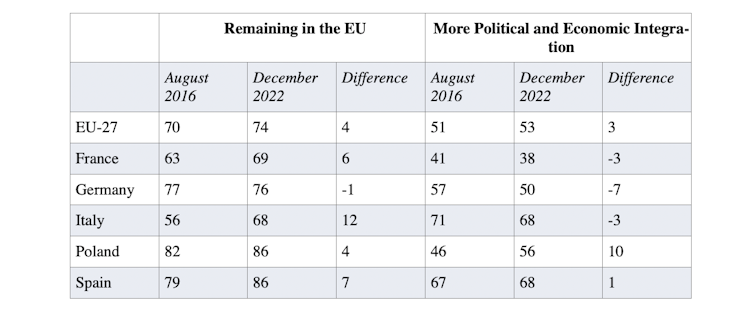

And indeed we’ve seen support for remaining the EU solidifying over this period – even after the initial referendum bump. In Spain support for staying in the EU has increased by 7 percentage points and even in Italy it is up by 12 percentage points.

Attitudes towards the EU in August 2016 and December 2022

However, while support for remaining in the EU is healthy, that does not mean people are looking for deeper political and economic integration in Europe. One does not necessarily translate into the other. While around 53% of Europeans wish to see more integration, there is significant variation across countries – which is very important for a project that is meant to work well for all its member states.

Support for more political and economic integration is high in Italy and Spain (68%) but low in the Netherlands (37%) and France (38%). In some countries, including Poland, support for more integration went up post-Brexit vote but in others, such as Germany, France and Italy, it went down.

So while Brexit did not trigger further departures from the EU or even a strong movement in that direction in terms of public opinion, it also hasn’t delivered increased enthusiasm for “more” Europe. That suggests the exit risk is not over, particularly if the UK proves able to mitigate the economic and political fallout of Brexit in the longer term – or if the EU 27 seems to be worse off politically and economically in the same timeframe. So far, Brexit is seen by much of the European public as a mistake – but how long will that last if the tide turns for the UK?

Catherine de Vries receives funding from a European Research Council Consolidator Grant (GA No. 864687).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.