An implant that turns brain signals into words could give a voice to those unable to talk.

The new device turns thoughts into words by decoding signals from the brain’s speech center to predict what sound someone is trying to say.

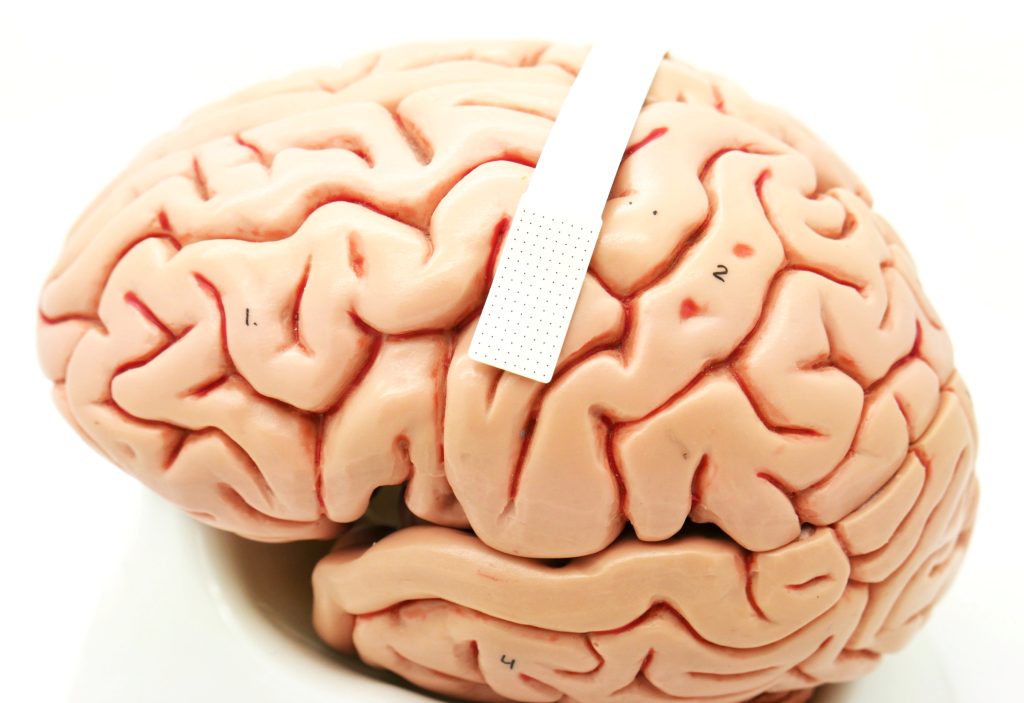

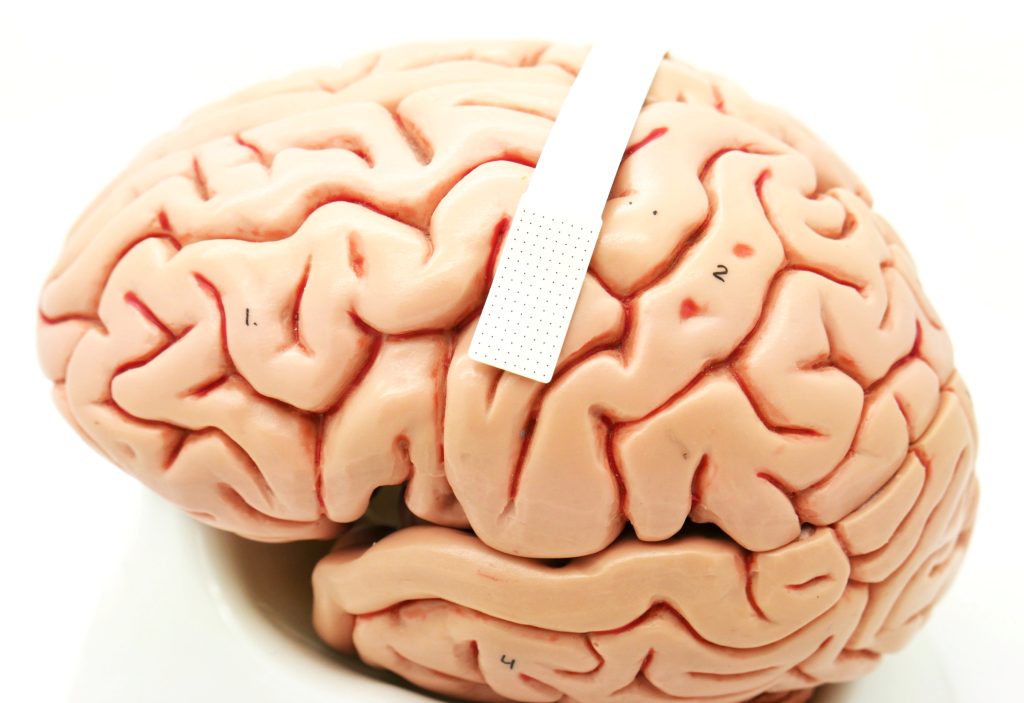

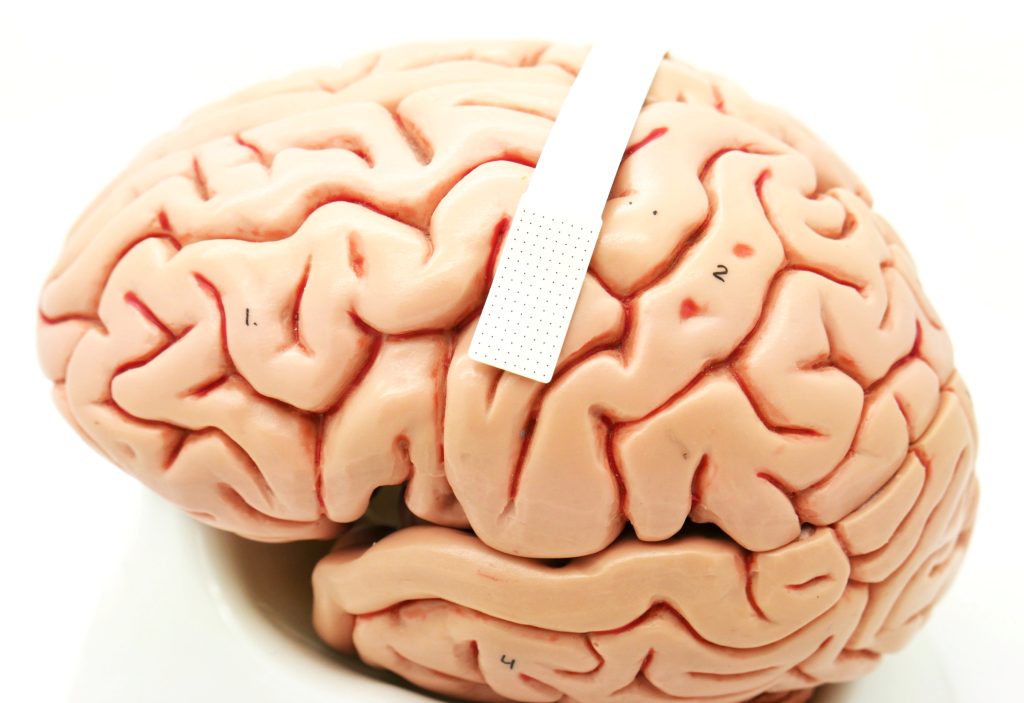

The implant, the size of a postage stamp, contains 256 microscopic sensors that can allow recipients to communicate on a brain-computer interface.

A device no bigger than a postage stamp (dotted portion within white band) packs 128 microscopic sensors that can translate brain cell activity into what someone intends to say. DAN VAHABA/DUKE UNIVERSITY/SWNS.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, could help people with ‘locked-in’ syndrome and others where current communication technology is very slow.

At present the best speech decoding systems work at around 78 words per minute, about half the speed of normal speech.

“There are many patients who suffer from debilitating motor disorders, like ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) or locked-in syndrome, that can impair their ability to speak,” said Dr. Gregory Cogan, a professor of neurology at Duke University’s School of Medicine and one of the lead researchers involved in the project.

“But the current tools available to allow them to communicate are generally very slow and cumbersome,” he added.

The team decided to improve the number of sensors on the device that lies on top of the brain

The Duke Institute for Brain Sciences specializes in making high-density, ultra-thin, and flexible brain sensors on medical-grade plastic.

Neurons just a grain of sand apart can have wildly different activity patterns when coordinating speech, so it’s necessary to distinguish signals from neighboring brain cells to help make accurate predictions about intended speech.

The device was then tested on four patients requiring the team to place it, test it, and then remove it in patients who were undergoing brain surgery for some other condition, such as treating Parkinson’s disease or having a tumor removed.

“We don’t want to add any extra time to the operating procedure, so we had to be in and out within 15 minutes. As soon as the surgeon and the medical team said ‘Go!’ we rushed into action and the patient performed the task,” said Cogan.

Participants heard a series of nonsense words, like “ava,” “kug,” or “vip,” and then spoke each one aloud.

The device recorded activity from each patient’s speech motor cortex as it coordinated nearly 100 muscles that move the lips, tongue, jaw, and larynx.

A device no bigger than a postage stamp (dotted portion within white band) packs 128 microscopic sensors that can translate brain cell activity into what someone intends to say. DAN VAHABA/DUKE UNIVERSITY/SWNS.

Afterward, graduate student Suseendrakumar Duraivel, the first author of the new study, took the neural and speech data from the surgery suite and fed it into a machine learning algorithm to see how accurately it could predict what sound was being made, based only on the brain activity recordings.

For some sounds and participants, like g in the word “gak,” the decoder got it right 84 per cent of the time when it was the first sound in a string of three that made up a given nonsense word.

Accuracy dropped, though, as the decoder parsed out sounds in the middle or at the end of a nonsense word. It also struggled if two sounds were similar, like p and b.

Overall, the decoder was accurate 40 percent of the time.

Although that doesn’t sound too good it was quite impressive given that similar brain-to-speech technical feats require hours or days’ worth of data to draw from.

The speech decoding algorithm used, however, was working with only 90 seconds of spoken data from the 15-minute test.

The team is now working on a cordless version of the device with a recent $2.4M grant from the National Institutes of Health.

“We’re now developing the same kind of recording devices but without any wires.“ You’d be able to move around, and you wouldn’t have to be tied to an electrical outlet, which is really exciting,” added Cogan.

“We’re at the point where it’s still much slower than natural speech but you can see the trajectory where you might be able to get there,” said Co-author Dr Jonathan Viventi.

Produced in association with SWNS Talker