Editor’s note: This story is a collaboration between the Texas Observer and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.

It was late afternoon when a small group traveling in a white Ford F-150 approached a humanitarian aid camp near Sasabe, a remote Arizona community along the U.S.-Mexico border. The visitors walked among tents, blue tarps, and nonperishable food—surveying the camp and filming its occupants. The uninvited guests, who appeared to have left their firearms in the pickup, aimed cameras at immigrants who dotted the cluttered encampment; some had traveled thousands of miles to reach the United States.

Humanitarian workers with the Arizona-based advocacy group No More Deaths immediately confronted them: “This man is filming. He’s refused to stop,” one volunteer told migrants clustered nearby. The camera continued to pan across the camp. Only when an aid worker again implored them to leave did the group begin to move. As he left, the leader—a 27-year-old man by the name of Cade Lamb—audibly accused volunteers of “aiding and abetting false asylum-seekers.”

Soon after, the video appeared in a fundraising email for Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb, a longshot U.S. Senate candidate in the July GOP primary—and Cade’s father. In a campaign Instagram post, Sheriff Lamb said he’d sent his son to film the camp. “Look at all these military age men! … Does this not look like a terrorist camp right here on our southern border?” he exclaimed, echoing inflammatory slogans used by other right-wing politicians to target charities that serve immigrants in Arizona and Texas.

Cade Lamb is the founder of the Sonoran Asset Group—one of various vigilante organizations that target aid workers and migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border.

On January 20, just three days after Cade’s aid camp visit near Sasabe, another group assembled on a ridge overlooking the Rio Grande in Texas and stood over five seated migrants. Some of those standing were armed with long guns or pistols and one wore tactical gear; they questioned the migrants, all young men or boys, while filming them.

“Y’all look sketchy as shit today,” said Greg Gibson, leader of the North Carolina United Patriot Party.

Gibson had driven from North Carolina to Eagle Pass, a small city on the Texas-Mexico border, where he ended up searching for migrants alongside other armed vigilantes he told the Texas Observer he’d recruited mostly online. They congregated at the border for an organized mission that Gibson called “Operation Hold the Line”—a reference to a 1990s Border Patrol operation in El Paso meant to deter migrant crossings.

Gibson and his recruits traveled around Eagle Pass in a caravan, guided by two right-wing bloggers from San Antonio who frequently post videos talking about the “invasion,” to patrol an area already highly militarized by Governor Greg Abbott’s multibillion-dollar border enforcement project Operation Lone Star.

Up on the ridge above the river, Gibson ordered the migrants to stay put. “Tell ‘em to stay here!” he yelled. “Quédate aquí,” one of the Texas bloggers translated for the migrants, who remained seated and looked concerned in the video.

Soon after, Border Patrol vehicles drove up the ridge, and a helicopter whirled overhead. Then, the vigilantes climbed into their private vehicles and continued their tour of Eagle Pass.

The same day, spotters in an FBI surveillance plane saw someone pointing a weapon at a migrant, and agents reported that people were “possibly being held at gunpoint.” The Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) dispatched officers, who confronted and questioned Gibson’s group. No one was arrested for pointing a gun at migrants, though one of the armed men had a domestic violence conviction, public records show, and could not legally carry a weapon. An officer also warned group members that they were trespassing according to a police report and federal court records.

All along the border, a monthslong investigation by the Observer and Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting has found, organized vigilante groups are filming themselves conducting patrols, taking photos of themselves alongside law enforcement, and sharing footage online to solicit donations, promote their work, and recruit new members. These vigilantes wear camouflage and tactical gear, issue orders, and detain and even point guns at migrants. The vigilantes have forged relationships with local and federal law enforcement, particularly in several border counties in Arizona and Texas. These ties appear to elevate the risk of violence in already volatile areas, and such collaboration raises questions about the extent to which vigilantes are illegally attempting to do the work of law enforcement or violating other laws.

“It raises a level of concern on my behalf that the law is not being applied fairly and equitably,” said Ken Magidson, who oversaw prosecutions along a wide swath of the border as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Texas from 2011 to 2017. “If the facts as you just stated are true, then apparently some people are above the law.”

Law enforcement collusion with vigilantes in Texas and Arizona runs the gamut from sheriff’s deputies showing groups around to police collaborating with—and not arresting—members with prior criminal convictions who were illegally carrying guns, according to social media posts, public records, court documents, and interviews.

In several cases, law enforcement failed to arrest or charge individuals who were repeatedly filmed committing suspected crimes in front of officers, including one case in which multiple alleged violations of the law were documented in a police report.

Some members of vigilante groups portray themselves as the border’s “neighborhood watch,” promoting themselves on social media as humanitarians who pray over migrants, rescue them from the Rio Grande, and offer medical care for minor wounds. But some have also spread conspiracy theories, threatened unarmed individuals, and damaged humanitarian aid and water stations meant to keep migrants from dying of thirst in remote swaths of land along the border. A few have deployed drones to surveil migrants. In 2009, three anti-immigrant militants murdered Raul Flores and his 9-year-old daughter, Brisenia, in the small Arizona border community of Arivaca. All three were convicted; two were sentenced to death, and one to life in prison.

Citizen militias are illegal in both Arizona and Texas, but in some cases police appear to be tacitly approving border vigilantism, which experts say will embolden bad actors.

When local authorities do nothing or express approval, vigilantes feel they can operate without consequences, “which is in my view very very problematic,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, director of the Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors at the Brookings Institution.

Armed anti-immigrant vigilante groups have a long history along the U.S.-Mexico border. Since at least the 1970s, white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan have scoured the border, often attempting to enforce immigration on their own. Following the birth of the modern anti-immigrant movement in the 1970s and ’80s, vigilantes reorganized into “Minuteman” groups, imploring the George W. Bush Administration to crack down on migrants illegally crossing the southern border. Today’s border vigilantes have become emboldened amid increasing political rhetoric about a border “invasion” and fears of migrants “replacing” white Americans.

In the leadup to the 2024 election—with border crossings surging last year and former President Donald Trump planning a migration crackdown if he retakes the White House—bearing arms to “secure the border” has become a siren call for many on the far right.

Some leaders, including the Texas governor, have arguably endorsed using violence to stop migrants. “The only thing that we’re not doing is we’re not shooting people who come across the border, because of course, the Biden administration would charge us with murder,” Abbott said in a January 5 radio interview. At a press conference a week later, Abbott backpedaled on these comments, saying he was simply distinguishing between what actions are legal, and which are not.

At a February 4 press conference, when asked by the Observer if he would denounce vigilantism, Abbott said, “Law and order needs to be left to states, to law enforcement, to authorized entities. We don’t want anybody taking any type of vigilante action. We believe in public safety, and that means the safety of everybody. The lives of everybody are important, and we don’t want anybody to be harmed in any way. All that we want is to enforce the immigration laws of the United States.”

In Arizona, lawmakers this year proposed to amend the state’s “castle doctrine,” which already allows property owners to use or threaten deadly force if they feel threatened by a trespasser in their home or yard, in certain circumstances. House Bill 2843 would have expanded where such force could be used, to include land owned by farmers and ranchers along the border. The bill passed the legislature in April, but was vetoed by Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs.

In both Arizona and Texas, some prominent law enforcement personnel and politicians have closely aligned themselves with border vigilantes.

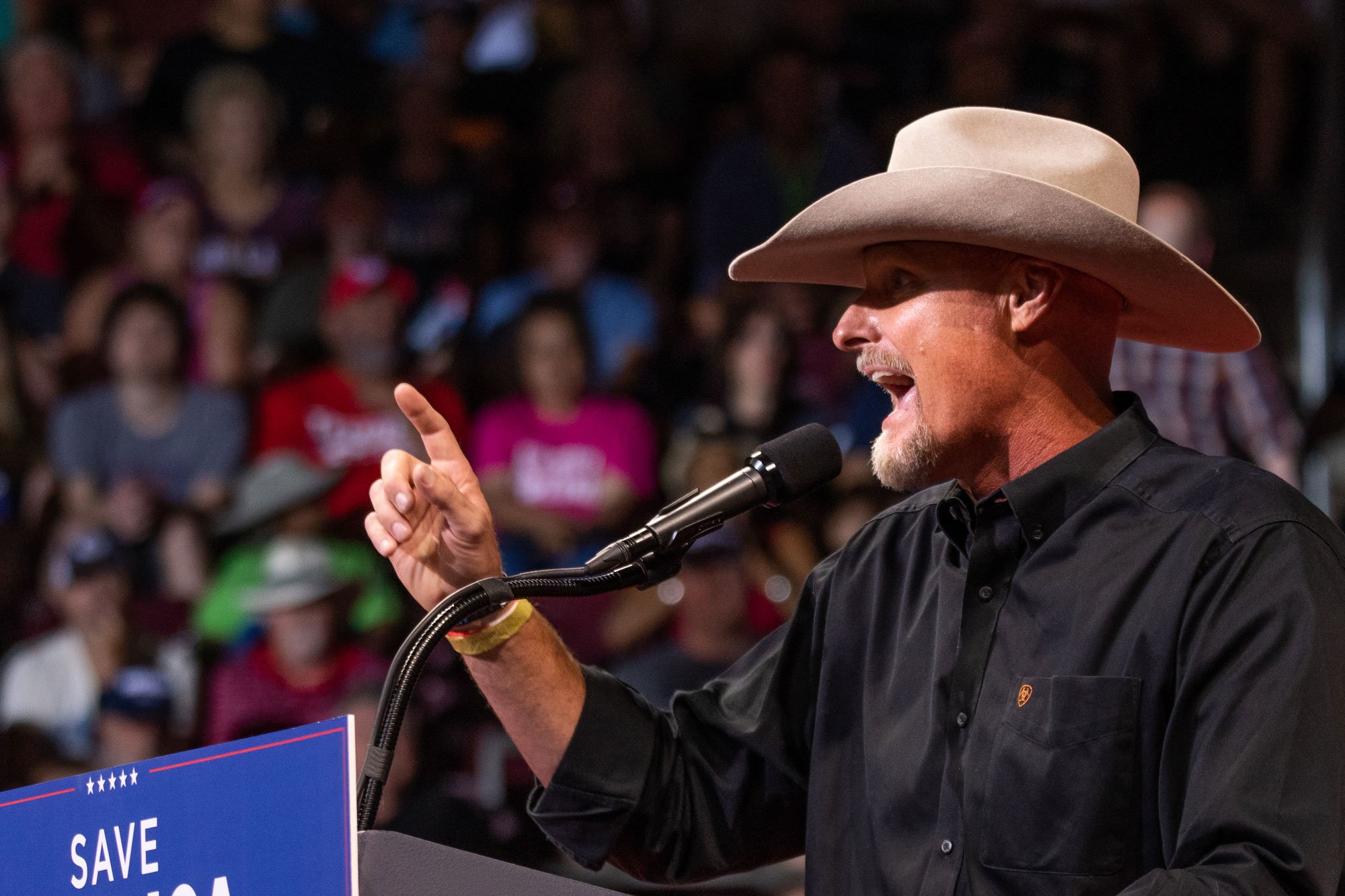

Rising right-wing Sheriff Mark Lamb, the outgoing top cop of Pinal County, has enjoyed the limelight after appearances on networks like Fox News, and speaking engagements with Trump at the White House and his Mar-a-Lago resort, where he warned against an “invasion” of immigrants. Now, Lamb is publicly elevating his son Cade’s vigilante group as part of his U.S. Senate campaign. The campaign did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Cade Lamb founded his organization in September 2022 as an LLC based in a one-story house in Eloy, Arizona, a town of 15,000 people that is home to a massive for-profit private prison used as an immigrant detention center.

Lamb’s company has no website, and he is listed as its manager on its state filings. On its Instagram account, Sonoran Asset Group says it does political consulting.

On his personal Instagram page and Sonoran Asset Group’s Instagram profile, Lamb shares footage of himself questioning and harassing migrants, whom he claims are collaborating with Mexican cartels. He often describes migrants as “military-age males.”

“We’re gonna see a real live border crossing, boys!” he declares in one video, while filming four men traversing a section of the border wall beneath the desert sun.

Several years before Cade’s father, Sheriff Lamb, launched his Senate campaign, he’d formed relationships with other vigilantes and far-right organizers. Toward the end of Trump’s presidency, he catapulted himself into far-right celebrityhood with public declarations of his refusal to enforce certain laws like Arizona’s extended COVID-19 stay-at-home order. His county does not touch the border and his office in Florence is more than 100 miles from Mexico, yet he’s fashioned his public image as a border sheriff, headlining a 2023 Turning Point USA documentary series called Border Battle.

At a June 2021 event hosted by the far-right Federation for American Immigration Reform in Sierra Vista, Arizona, Sheriff Lamb posed with dozens of other sheriffs alongside right-wing vigilantes to call for aggressive border security measures. Months before speaking at that event, he escorted U.S. Senator Marsha Blackburn on a guided borderlands tour with Christie Hutcherson, the leader of the Florida-based anti-immigrant group Women Fighting for America—a self-described “frontline freedom organization.”

Hutcherson addressed a pro-Trump rally in Washington, D.C. on the eve of the January 6 insurrection and was named in a presidential records request as part of the congressional January 6 investigation. In 2021, Hutcherson visited the border in Arizona and Texas with a drone that can fly miles away from the operator and detect people using thermal imaging. Hutcherson has said in Facebook videos and an interview that she’s partnered with Sheriff Lamb and Sheriff Mark Dannels of Cochise County, Arizona, to help them surveil the border using drones. But she denies she assists in arrests: “We let law enforcement do law enforcement’s job. It’s not our job to detain them,” she said. “If they’re short-staffed or short-handed, and they asked us to—that’s a whole different ball game.”

In an email, a spokesperson for Dannels said the sheriff’s office does “not encourage outside organizations to participate in any patrol/enforcement actions,” though the sheriff prioritizes “maintaining autonomy and collaborations with non-law enforcement groups” and considers that “community policing is an internal function utilized for the betterment of our communities.”

A spokesperson for the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office said the agency does not have formal contracts or partnerships with Hutcherson or her group, Women Fighting for America.

In an interview, Hutcherson said she offered her tech and time to U.S. Border Patrol agents and to local law enforcement, for free.

She also has tried to solicit drone contracts with at least one border county, Kinney County, and and state law enforcement in Texas, though there is no record of her receiving a contract with either agency, according to the state comptroller’s office and interviews.

Patriots for America (PFA), a North Texas-based Christian vigilante group led by Samuel Hall, a former missionary and longtime car salesman, claims to have worked with the Kinney County Sheriff’s Office to intercept migrants since 2021. In social media posts, Hall describes his team as a militia, though private paramilitary groups are illegal under the Texas Government Code. In livestreams, he emphasizes the group’s goal is to be the “hands and feet of Christ.”

In an interview, Kinney County Sheriff’s Office public information officer Matt Benacci denied Hall’s group has any formal arrangement with the department, though PFA members have frequently posted information about their patrols. Benacci also told the Observer that some PFA members couldn’t pass when the sheriff’s office conducted background checks in the fall of 2021, when they first offered to volunteer. Hall declined to comment for this story and turned down multiple interview requests.

Photos and videos posted online show PFA members patrolling rural Kinney County and other swathes of the Texas-Mexico border.

Kinney County, which has only 3,150 residents, has been a focal point of Abbott’s Operation Lone Star. In the last three years, thousands of migrants have been arrested there, often for trespassing, by law enforcement officials. In April, Abbott’s office issued a press release boasting that his multicounty effort so far “has led to over 507,200 illegal immigrant apprehensions and more than 41,500 criminal arrests, with more than 36,900 felony charges.”

In October 2021, Kinney County commissioners voted to approve the deputization of 10 reservists for the sheriff’s office. At the meeting, Hall seized the moment to address county lawmakers, saying his group already had a presence in the county assisting with immigration enforcement. “We’ve lost our income to come down here to protect this county when nobody else is doing it,” he said. “We’re going to bring the right quality men that realize the political atmosphere, that realize exactly what’s at stake, and we’re going to protect each and every one of these citizens.”

That fall, Sheriff Coe told The Wall Street Journal that his office was considering formally deputizing members of his group as unpaid volunteers. In a video posted to Facebook days after the meeting, PFA volunteer Terry Dean Anderson claimed the background check and deputization process was underway.

Hall insists he vets his members, but three PFA volunteers already had criminal convictions prior to beginning their operations on the border in 2021, court records and police reports show.

Anderson was arrested in March 2022 by state police—not the sheriff’s office—in Kinney County on charges of being a felon in illegal possession of firearms and metal body armor while traveling with the group. In December 2021, Hall posted video footage online of Anderson armed in the presence of Kinney County Sheriff’s Office deputy Sergeant Manuel Pena.

PFA’s “captain” and second-in-command, Shawn Tredway, has a history of misdemeanor convictions in Texas spanning 1998 to 2011 that include domestic assault, possession of a dangerous drug, possession of a controlled substance, and driving while intoxicated, according to a state police criminal conviction report and court records. In March 2022, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) sent a letter to officials in Collin County requesting documents related to Tredway’s domestic assault conviction as part of an “official federal firearms investigation.” The ATF agent overseeing the investigation into Tredway did not respond to questions sent via email.

Pena said in a phone call that he showed PFA around when they first arrived in town in 2021. Brad Coe, the sheriff, did not respond to multiple interview requests.

The Kinney County Sheriff’s Office was the subject of a formal civil rights complaint from the Texas Civil Rights Project, the ACLU of Texas, and other civil rights groups in December 2021. The complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice, updated in February 2022, alleged in part that “the Patriots for America vigilante group is directly collaborating with the Kinney County Sheriff’s Office, including through repeated meetings and–in at least one instance–in detaining migrants, and that on at least one occasion they seem to have collaborated with the Texas National Guard as well.” Advocates urged immediate action given that such activities appeared to be expanding. But the federal government never responded, David Donatti, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Texas said in an interview.

Separately, the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University Law Center sent a letter in May 2022 to top Kinney County officials, protesting the sheriff’s relationship with vigilante groups. “[Texas] laws make clear that the usurpation of law enforcement authority by Patriots for America, Women Fighting for America, or any other private paramilitary organization is illegal under Texas law and should not be condoned or supported,” Mary McCord, the organization’s executive director, wrote.

Hall has also posted photos or boasted on social media of relationships with law enforcement in Uvalde, Val Verde, and Maverick counties, along with the former mayor of Uvalde, Don McLaughlin.

Anderson, Hall, Tredway, and another PFA volunteer responded to the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, which claimed the lives of 19 students and two teachers. For at least 8 minutes, videos show, they walked around and filmed beyond the police line.

Before and after the Robb Elementary school shooting, Hall offered to have PFA patrol Uvalde, McLaughlin said in an interview. But the mayor said he refused and was unaware until being questioned by the Observer that some group members had shown up at the scene of the massacre.

The PFA members who showed up at Robb were not heavily armed. “It could have turned out a lot worse than it did had they shown up in force,” McLaughlin said. “Because officers are trying to deal with one scene … and [police] don’t know who they are.”

An hour west, in Val Verde County, Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez approached several ranchers in 2021, asking if they needed PFA’s services, according to emails obtained by the Observer and a related report by the Los Angeles Times. Martinez did not respond to interview requests for this story.

Amy Cooter, a Middlebury Institute of International Studies sociologist and expert in contemporary U.S. militias, said introductions by elected law enforcement can help vigilantes: “They feel more legitimized and more like what they do will be overlooked or even encouraged by law enforcement.”

Hall has also posted pictures of himself posing inside the sheriff’s office in Maverick County, home to Eagle Pass, alongside the local sheriff, Tom Schmerber. At first, when asked, Schmerber denied Hall had ever visited there. After a reporter texted him the photo, Schmerber recalled a brief 20 minute meeting and said he had forgotten what Hall’s face looked like. In one of the interviews, Schmerber insisted he doesn’t approve of armed vigilantes. “If someone’s going to help, it’s going to have to be a law enforcement officer,” he said.

Even if law enforcement does not directly work with anti-immigrant vigilantes, posing for pictures with them is problematic, Cooter said. “It’s almost like a free pass to do whatever you want saying, ‘I’ve cleared all this with law enforcement,’” she said. “Even the well-meaning groups I have encountered, they tend to retrospectively exaggerate just how much free license that kind of interaction gets them.”

Other vigilantes have posted photos or videos to showcase their rapport with federal border enforcement agents. Veterans on Patrol, a militant group which has operated sporadically in southern Arizona for nearly a decade and recently traveled to eastern Washington State, has leveraged what it claims are relationships with law enforcement officials to solicit funding and members. The group’s title is something of a misnomer: Its leader and founder, Michael “Lewis Arthur” Meyer, is not a veteran.

Vigilantes have also shared drone surveillance footage with U.S. Border Patrol agents, according to footage analyzed for this story and shared by the Western States Center, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for public policies to combat domestic extremism.

The grainy dashcam footage, taken in 2018 or 2019, shows a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) checkpoint 25 miles west of Tucson in the Arizona desert. Meyer narrates as a green-and-white Border Patrol pickup truck pulls up. The truck stops, and an agent steps out and approaches Meyer’s vehicle.

“Hey man … you guys are very effective. You can’t talk to every agent like you can talk to me,” the agent says.

Meyer had not traveled to the checkpoint empty-handed. He brought footage captured from a drone. The agent offered to “take the [memory] card or you can text [the footage] to me either way. I’ll get you another card back.”

During their conversation, the agent nonchalantly said he’s “not the FAA,” referring to the Federal Aviation Administration, which regulates airspace. The agent continues: “If you guys can see [migrants], we can get ‘em.”

“I have a few things that go bang and go fast if you know what I mean.”

In recent years, federal border enforcement officials’ tolerance of paramilitary groups has had frightening consequences for migrants. In 2019, members of the United Constitutional Patriots were able to establish a camp, raise funds, and proliferate in New Mexico because they had the tacit blessing of the U.S. Border Patrol, according to McCord, the Georgetown-based constitutional law expert.

That militia was detaining migrants, “completely without any authority,” McCord said. Then, they would hand them over to Border Patrol. Agents weren’t actively asking the self-described militia associates to continue detaining migrants illegally, McCord said, but they also weren’t taking any action against the vigilantes for breaking the law. “They were just ignoring the fact that what these folks had done was illegal,” she said.

CBP spokespeople declined requests for an on-the-record interview and did not respond to written questions for this story.

Like Veterans on Patrol, United Constitutional Patriots touted relationships with law enforcement to encourage prospective volunteers and vie for donations. The now-defunct paramilitary group was led by Larry Mitchell Hopkins, who had criminal convictions in multiple states for weapons charges and impersonating a peace officer. Hopkins was arrested again in New Mexico in 2019 and charged with illegal possession of a firearm—but only after footage of his group detaining several hundred migrants at gunpoint went viral.

Border Patrol agents appear to lack top-level guidance or official policies for engaging with vigilantes.

U.S. Senator Ed Markey, a Massachusetts Democrat, identified this federal policy deficit in a letter last year in response to vigilante activity in Texas and Arizona by Patriots for America and Veterans on Patrol. The letter—sent to top officials at the Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, and CBP—described how border vigilantes have engaged in “unofficial or unsanctioned collaboration with law enforcement agents.”

Without federal action, the letter states, “Vigilante groups will continue to operate and weaken the government’s ability to maintain migrant safety, protect human rights, and defend the rule of law at the border.”

In January 2024, Markey introduced legislation that would impose criminal penalties on unauthorized armed militia activity. The bill has been referred to the Senate and House Judiciary committees for consideration.

In February, thousands of people around the country joined the “Take Our Border Back” trucker convoy tour, with stops in San Diego, California, Yuma, Arizona, and a ranch near Eagle Pass.

That weekend, a few armed vigilantes roamed the small Texas border city leaving residents uncomfortable even in their own Walmart parking lot. Several members of the Carnalismo National Brown Berets, a four-decade-old Chicano civil rights group, arrived from across Texas to provide security for local residents during a counterprotest. One Brown Beret, who goes by the Nahuatl name Canauhtli, called the convoy “Woodstock for fascists.”

The convoy’s influx of armed vigilantes left some residents exasperated. “We’re tired of it. This community is exhausted,” said local activist and Maverick County Democratic Party Chair Juanita Martinez.

Despite politicians’ claims to the contrary, Martinez added, there’s no invasion in her town—except by law enforcement officials and anti-immigrant groups. “They’re lying to you, pendejos,” she said to the Observer in a downtown café.

Among the vigilantes who have visited Eagle Pass is Gibson, the United Patriot Party of North Carolina leader.

“Should have goddamned learned English before you got over here! … Habla English here!” he barked at two migrants, according to a video he posted in November 2023.

In another, he pointed a flashlight at a group of six migrants walking in the dark, including two small children. “Sit down. Sit down. Sit! Sit!” he repeated. The migrants got on their knees. “These people put themselves and little children in danger,” he said, as his flashlight partially illuminated the faces of a woman and child, who appeared frightened and confused.

When asked about the incident, Gibson said “they weren’t afraid of us,” but a smuggler on the Mexican side of the river.

Despite living more than 1,000 miles from the border, Gibson, the North Carolina militia leader, returned to the border again in January. This time, however, he solicited backup.

People from other states heeded the call, including one with explosive plans.

Paul Faye, a 55-year-old from Tennessee, made arrangements to meet Gibson in Eagle Pass. Faye was supposed to serve as a sniper, and bought tannerite to make DIY explosives, according to an affidavit filed in federal court in February 2024 from an undercover FBI agent who had been watching Faye for almost a year. “I have a few things that go bang and go fast if you know what I mean,” Faye told the agent, according to federal court records.

Faye never made it to the border to meet up with the United Patriot Party in January; he was arrested on February 5.

Others were patrolling the Eagle Pass area with Gibson in January when the FBI surveillance plane spotted one or more people in the group pointing a gun at migrants. In an interview, Gibson said a “gentleman” with his group “did use his rifle looking through his scope” in lieu of binoculars to watch people cross the river. Gibson also told the Observer he denounces violence.

Texas Department of Public Safety officers questioned members of the group—including Gibson and 50-year-old Jeremy Allred, a Montgomery County resident, who was carrying “multiple weapons” despite a prior domestic violence conviction that made him ineligible to carry a gun, according to police reports. Officers detained Allred but released him after a federal prosecutor initially declined to accept the weapons charge.

In the aftermath, Gibson boasted to his Instagram followers that he’d only been warned by federal agents. “If any of these illegals … [said] they even felt threatened, just felt threatened by me, then I would be arrested.”

Allred returned to the border to rejoin the group a week later. In a motel parking lot in Del Rio, he again openly carried a pistol on his hip. This time, an FBI agent arrested him. As of March, he was still being held without bail on charges of unlawful possession of a firearm. He was subsequently transferred to a private prison and no further updates were available. The federal public defender representing him declined an interview request.

Still, Gibson has boasted about what he claims are positive relationships with law enforcement, including Border Patrol and DPS officers. “I would dare say they were cool with us,” he said in an interview.

When people like him are hanging out with the police, Gibson said, “The whole ‘domestic terrorist’ thing falls apart.”

Editor’s Note: Avery Schmitz has an agreement with Georgetown Law’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, which Mary McCord leads, for legal services related to reporting previously published by Lawfare, a nonprofit legal and policy publication.