We live in a world dominated by colossal corporations. The likes of Microsoft and Apple are bigger than most economies. Not long ago, however, a British company dwarfed these giants, yet few people know its history or the valuable lessons it can teach us today.

I am talking about the East India Company (EIC), an unrelenting force in world affairs from 1600 until as recently as the 1870s. Its history and importance are perfectly summed up by the Scottish historian William Dalrymple in his 2019 book, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company.

I read it last Christmas and could barely put it down. It spoke both to my south Asian roots and my accountancy specialism, since the company’s first governor, Sir Thomas Smythe (1558-1625), was an auditor. Dalrymple, who has lived most of his life in India, meticulously explains how this one company became the de facto ruler of the subcontinent for more than a century.

Welcome to our new series on key titles that have helped shape business and the economy – as suggested by Conversation writers. We have avoided the Marxes and Smiths, since you’ll know plenty about them already. The series covers everything from demographics to cutting-edge tech, so stand by for some ideal holiday reading.

The East India Company was set up as a “joint stock” company, meaning it was controlled by its investors. And it wasn’t just elite figures like the mayor of London who held stakes, but British people from every walk of life – from sandal makers to leather workers to wine merchants.

This model meant access to essentially unlimited finance, since more investors could always be found. They were attracted by the company’s official charter from Queen Elizabeth in 1600, which gave it an exclusive trading monopoly over India.

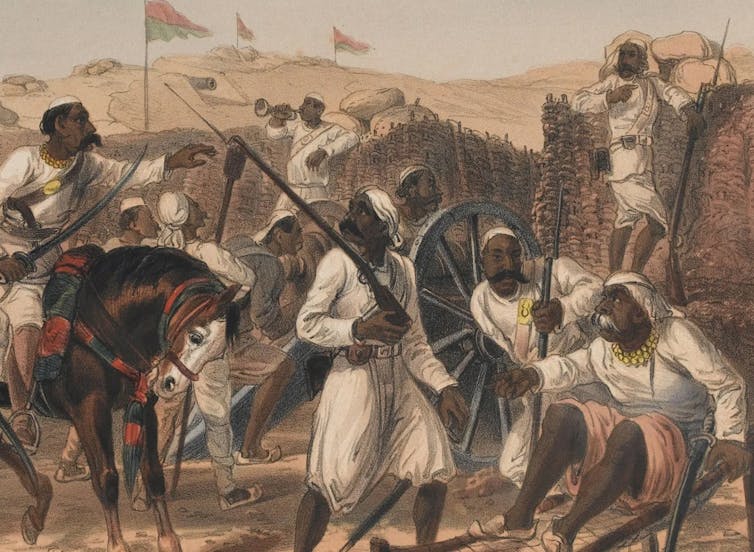

The company gradually grew in military might and was able to exploit the chaos and instability caused by the decline of the Mughal empire, which had ruled large parts of the subcontinent until the early 18th century (this is “the anarchy” Dalrymple refers to in the title).

His book details the greed and arrogance of important company figures such as Lord Robert Clive (1725-1774), who became the first British governor of Bengal, and Warren Hastings (1732-1818), the first governor-general of India. Clive is described as a “violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator”, though also an “extremely capable leader of the company and its military force in India”.

A pivotal moment came under his leadership in 1757, when he defeated the Bengali leader (the nawab) and his French allies at the Battle of Plassey. Dalrymple recounts how Clive personally entered the treasury of the nawab in the city of Murshidabad, and ended up taking most of it for himself. He “returned to Britain with a personal fortune then valued at £234,000” (£35 million in today’s money).

From Bengal, the East India Company came to exert control over large parts of the subcontinent, with numerous battles, massacres and atrocities along the way. Yet this victory in Bengal also ironically led to one of its biggest crises: the value of the stock had doubled on news of the company’s success, but then collapsed in 1769 after it had become overextended militarily and commercially, and faced a famine in Bengal.

Dalrymple describes how company tax collectors were ruthless during this famine, brutally enforcing high taxes in what was euphemistically described as “shaking the pagoda tree”. These would have been major human rights violations today, but weren’t enough to prevent a cash crunch in which the company was unable to pay creditors or taxes.

By this stage, the company was responsible for a staggering 50% of global trade. In 1773, it became the original institution deemed “too big to fail” as the British government stepped in with “one of history’s first mega-bailouts”.

The company paid with some restrictions in its autonomy, but remained extremely powerful for years to come. Its private army peaked at around 250,000 men in the early 19th century, bigger than that of the British army (Dalrymple likens it to Walmart having its own fleet of nuclear submarines). Thus, the colonial takeover of India was achieved not by state power but corporate strategy, backed by private military force.

It must have seemed like the company would continue indefinitely – but growing criticism of its tough trading tactics and corruption led to successive efforts by the British government to limit its power. The final straw was the mutiny of 1857, which started among Indian soldiers in the EIC army and spread across the subcontinent.

After it was put down by the British, with some 100,000 Indians killed, the government assumed direct control of India. So began the era of the British Raj. The EIC military was absorbed by the Crown and within a few years, the company was dissolved.

Moral lessons

For me, the most important takeaway from The Anarchy is summed up by a quote from one of its cast of characters, the 18th-century Tory politician and lord chancellor, Baron Edward Thurlow:

Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned; they therefore do as they like.

Dalrymple vividly describes how we can still see the results today in Powis castle in central Wales, of all places. It is “awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder, extracted by the East India Company … there are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display in any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi”.

The Anarchy reminds us that the most profitable and innovative businesses can become vessels for exploitation without appropriate accountability and governance. The book is on its way to becoming a modern classic for its analysis of this decay.

Today’s massive corporations lack the company’s military strength, and corporate governance has thankfully improved over the last couple of centuries. Yet these entities are still incredibly powerful. Among the world’s top 100 economic operators, almost 70% are corporations.

The biggest companies are set to dominate new technologies like AI, which will make them seem even more unassailable. The demise of the British East India Company at least reminds us that governments ultimately have the power to reassert themselves, if the will is there. Through all the corporate brutality and corruption on display, The Anarchy does carry that message of hope.

Anwar Halari does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.