Anna Rankin on a beautiful and profound meditation on grief

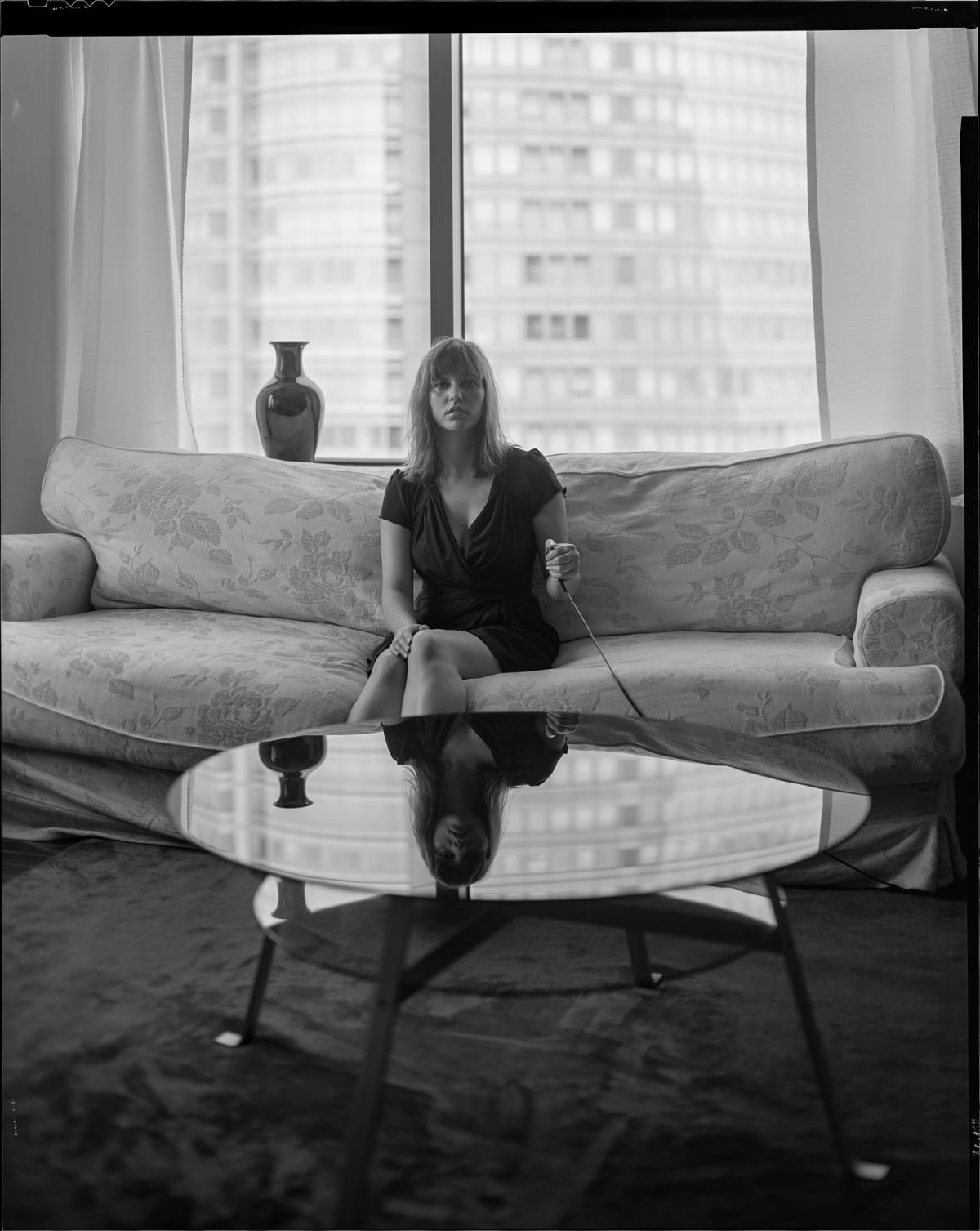

There is a young girl who died and she stares down the pages of a book as though she has foreseen her own past and future in one swift moment, and she insists on her rightful presence, and she haunts the periphery like mist, gathering her form into silent fog that rolls in off the sea and threatens to engulfs one's sight, and in this way she is transfigured in both matter and spirit and she will never entirely pass over.

It is generally an exercise in overdetermination to place too heavy an emphasis on a book’s cover but with Kōhine, a new collection of short stories by Colleen Maria Lenihan (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ireland), the central and glossed portrait of a young girl’s face - omniscient dark eyes disarmingly unyielding in their gaze, barrelling through time, leaving the viewer with the eerie impression of having been seen and exposed with peculiar clarity - is more operative than mere signpost; her face, emerging and receding through the navy and mauve shimmer of cityscapes and street signs of Tokyo, functions as with all spectral presences as a warning, an interloper into the present, as a call inward. Where the nighttime metropolis surrounding her form is shadowed and tessellated with vice and noise, neon writ across her skin, she remains intractable; she is the still point.

E kore au e ngaro / I shall never be lost reads the book's epitaph, and is an claim bestowed not only upon the author’s late daughter but Lenihan, too; it reads as a defiant beacon to light and inscribe her navigation across the chapters of her life. He kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea / I am a seed born of greatness, the whakataukī continues; an affirmation of whakapapa; history, spirit, culture inextricably bound and passed down.

Over 23 short stories that traverse cosmopolis Tokyo, Tāmaki Makaurau and rural Aotearoa, the author presents a profound picture of grief. It is not grief that disfigures but a grief fully surrendered to and therefore understood from which comes joy—not an emotion but a consequence—and such an amalgam begets wry humor, possessed entirely by those who have experienced great pain and made it out alive. The gift bestowed is therefore that rare trait possessed by even fewer: fierce insight.

While ostensibly fiction, these stories braid personal biography into their fold. If fiction is in this instance not a scalpel but a mirror Lenihan has both the requisite distance from and proximity to the characters she at times embodies, evades and transmutes; there is the sense that she arrived in life with a discerning compassion for those she intuited were quite like herself: those on the fringes, those who live close to the bone; those bequeathed with rare blessing and talent yet no clear blueprint for what to do with it, those without access; who took the circuitous route through life, those in possession of and thereby distracted by beauty irrespective of the darkness, and its cost, plainly visible on the surface, those who attempt, and fail, to give to others from their own yawning lack, those desperate, those who no longer care such is the intensity of their care, those merciful—whose justified anger masks unbearably raw tenderness; those made numb who seek to feel and will attempt anything to do so, those rapaciously desirous of the world, those who stand upright and unafraid, those who leave. Such types are commonly condemned as broken but that perhaps depends entirely on whether you believe the fragment makes the whole.

It must be stated that there is a lot of pain observed in this book. There is nothing hypothetical about it. There is a muted pain that at times uprears and shrieks; a pain that will be familiar to some, less so to others; this is a pain that sears; after the shock of recognition its memory colours every interaction, each story laced with foreboding doom; every decision aware of its own compromises and contradictions, every choice aware of its cost. No character possesses that most contemptible trait: naiveté.

*

The opening story, "Gnossienne No. 1", is a quiet and melancholic portrait of a piano teacher in Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, and in tone is correlative with its title; a subdued and euphonious piano composition by the French composer Satie. The teacher takes a train journey alone over a long weekend to a deserted beach to surf and ruminate. Evenings on the balcony he drags cigarettes, sips JD and Coke until night falls. Memories of a painful past relationship ebb in and out with the ocean; grey, silent, draped in fog.

Aria’s death, and the life of her mother Maia before, during and after the terrible event, is the leitmotif of the collection. It moves from Maia’s teenage years to Aria’s youth with her young mother, navigating life in Tokyo through failed relationships, precarious working conditions, sojourns to tropical retreats immersed in extraordinary wealth. A cast of fleeting characters populate the book, but it is Maia and Aria who bind it. Time in Kōhine is not linear; it whorls and unfolds; spirit meets bone and both are transformed; time is borderland; stories merge and diverge; with great skill Lenihan leads us through leaps of time and space. This conception of time is well established in Te Ao Māori, where the veil between the living and the dead is a gauze, as it is in the Celtic tradition, through ‘thin places’—sites and instances where the world is considered uniquely open, where the spiritual and material worlds converge and beings, the living and the dead, pass forth and through.

*

From the opening story the scene interlinks and shifts to Maia’s dawn confrontation with the body of her dead daughter at the police station. Together they travel home to Aotearoa, the sharp neon of Tokyo easing to scenes of boil-up and fry bread, “patches of scrubby vegetation under a colourless sky”. Back in Tokyo, Maia moves impassively through the day; she sees her daughter in the faces of schoolgirls on the train. “Why are you alive”, she deplores; one night, beset with sleeplessness, she has a surreal out of body experience in which her grief transforms, and in the denouement experiences sublime release.

"Ruru" is raw and desperate (and like more than a handful of other stories in Kōhine, recalls Mary Gaitskill’s classic short story collection, Bad Behaviour), chronicling the sexual desires, despairs and obsessions of the young and beautiful. The protagonist moves in with Tim, whom she barely knows, and it’s reckless and bittersweet; two people, one of whom is drowning, who cannot help the other: “she wonders what kind of person would let a stranger move in after a drunken hook-up, but I figured someone kind of crazy, like me”. Over a season seduced by the prospect of love and stability under the forest canopies of Te Henga, a watchful ruru encroaches and haunts, impervious to her insistence on her happiness—a happiness with shadows. “You snooze, you lose” she retorts one night when asked why she’s pathologically awake. In Lenihan’s hands this rather trite phrase is menacing, freighted with sadness. She plays house; drinks white wine, lays on the bed in lingerie awaiting her man’s arrival home from work. She mentions what she describes as her "great loss" inside a banal conversation lubricated with wine and music one night because there is no place large enough to put it. Throughout the book every warm moment - in "Ruru", it's sucking mussels on the beach, being caught out in the tide - is shadowed with its own demise.

The stories navigating Maia’s childhood, with its Uncles and Aunties, her books and her crucifix, are told in a more youthful and rudimentary voice, laconic and simple and rendered in an almost diaristic mode; remembering innocence. It's a stylistic trick used ingeniously elsewhere, where impressions are recounted through Aria’s voice, which has the curious effect of melding mother with daughter; a formula further emphasised in the story "Spirit House", where Maia and 14-year-old Aria, vacationing in a tropical location and dressed in colorful skimpy clothing, are mistaken for two friends and hit on in a bar. Earlier in the day, on a boat, Maia falls quiet and describes, during an earlier trip to the island, hearing the voice of God through the limestone cliffs rising from the emerald sea; He instructed her to listen. Maia considers at times whether she’s neglectful; Aria feels invisible, and amidst the whirl of lights and throngs of people immersed within the giant screens and blaring neon at Shibuya Crossing remarks to her mother that she believes no one would stop should she drop dead on the street. For once, she adds, she has her mother’s full attention; Maia replies that she knows exactly what Aria means.

The stories depicting Maia in her role at the Gentlemen’s Clubs of Tokyo are compelling; the thick soup of the city in summer, the glow of dusk over the sex and souvenir stores snaking the alleys, the red velvet clubs, the mirrored walls refracting tiny shards of light cast by spinning discoballs. Girls from an array of countries doing lines in laced thongs and bandeau dresses; their conversations blunt, alluring, crude, hilarious; Lenihan is precise with her application of levity. Maia is a greenhorn but a quick learner—and a hustler; she makes cash quickly; she knows the cost of things and yet how lightly things must be held and she does not, she states, despite her contrary proclivities, judge people who stay.

"Love Hotel" illustrates the malaise and banality that marks easy sex in Tokyo, where couples, mostly strangers, meet in themed rooms and engage in whatever meets their desires, watched over by two comical workers. There's a bored schoolgirl in pink fur handcuffs cradling a lonely salaryman, looking upon him with disinterested contempt, and other characters include a fake-titted blonde throwing sex toys at her passed-out companion before exiting the room, handbag stuffed with dildos and vibrators he’ll have to foot the bill for upon waking.

"The Storm" elaborates this theme; a bleak tale of a quartet: two Barclays traders and two former dancers at the world’s highest-earning Gentlemen’s Club are loaded, and loaded up with cash. “I don't know why we keep up this charade of being people who go out for nice dinners when all we want to do is get on it” the unnamed protagonist observes. Friends who have inherited rather than chosen each other, it seems; foreigners in Japan stick together irrespective of how they might genuinely feel about one another. A sex club sees the decidedly amusing degradation of a trader followed by another day of getting loaded. Money punctuates all encounters; she is gifted a gold Bulgari snake pendant with green eyes on a Bali vacation from her fiancé, Jeff; Bali is a hedonistic nightmare daze fuelled by a regime of coke, mushrooms, whatever, culminating in a tripped-out swim and a thunderous storm accentuated with the kinds of blurry and incoherent conversations—though at the time, deeply meaningful, profound—one has on good drugs.

*

In "Just Holden Together", Maia is laden with her past; a sensation further emphasised in the oppressive surrounding landscape; her mind engaged in a dialectical torment between what she carries and what she knows might, could, be done with it. There’s boil-up and pūhā, there’s pot, guns; “Bad look, bro”, Maia thinks to herself as she eyes up her brother, Tāne, in socks and jandals. There’s a visit to Aria’s grave, strange dreams, Maia’s mother dresses down a patched gang member she once taught. Some of the liveliest conversation in the collection occurs in this story and it’s enough to not only bruise one's heart but break it right open.

Lenihan's story "Private Dancer" is a darkly funny depiction of a grim and shabby downtown Auckland in the 1990s; flush with heroin, seedy bars and desperate losers, 15-year-old Joy, eyes thickened with kohl and dressed in a cut off Metallica T-shirt and cherry Docs, runs away from home, parents who aren’t her real ones, she says, and hitches a ride to Auckland with a Black Power foursome in a Valiant; "Are you scared, girl?", she's asked, "Na", she replies, dragging on a joint. With no money or a place to live, she becomes a stripper; she gets so high she lets a DJ tattoo a Grim Reaper on her back; she wears Zambesi, she gets fired, she gets hired at a cheap joint peddling porn and private booth dances; she is bored and avoids being raped by faking an epileptic fit; she and her equally lovable, wholly apathetic friend lack motivation to change the CD for weeks so they dance solely to Oasis during a peep show; they smoke and gossip against the concrete walls outside, they observe the squalid depravity that marks their line of work and remain nonchanlant about it all. To contrast the inordinately wealthy and elite Gentlemen’s Clubs of Tokyo to Auckland’s in the bleak years of the 1990s is a study in the finest of dark humour.

The book sets its final stories in a contemporary mode; we are here, and now. In a collection concerned with arrivals and departures Maia is, if not arrived, in one place. She channels her displacement drive and ambiguous, unfocused desire into her online life, embarking on a disjointed relationship of sorts, minus the sex. He is a hapless but clever film actor in Los Angeles in and out of relapse; they are each other’s anchor; it makes the point that relationships orchestrated online is to cure the loneliness until you don’t need to anymore, until you do.

She engages in depressing episodes with lacklustre and indecent men who don’t deserve her time, who project their fantasies onto her then disappear, “hungry ghosts who roam the periphery of her life, online and off”. She receives dick pics and sexts from exes currently entwined in relationships. Astrid, a wise and older writer, advises her to take care with her whare tangata. She warns: “I’ve learned not to deal with men with lower energy than mine…when you enter into a union with someone, you take on their energy.”

Beginning with death, Kōhine closes with departure. Joyce’s closing scene from The Dead played as a refrain as I read; in a portrait describing snow falling, touching all across the earth as it does so, he writes: "It was falling too upon every part of the lonely churchyard where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end upon all the living and the dead."

Kōhine is a stunning taonga by a remarkably accomplished author who has given us a work that further places Te Ao Māori firmly at the forefront of literature in this country. It takes up those on the margins, those in the shadows who yet emerge in light; those scattered across the world who do not and will not forget who they are. This book seems to belong to them. It takes up, too, a world that belongs to all who have lost, been lost, been found, and a world that belongs to those beyond the gauze.

Kōhine by Colleen Maria Lenihan (Huia, $25) is available in bookstores nationwide. ReadingRoom has devoted all week to this very, very good collection of short stories. Tuesday: a self-portrait. Wednesday: a a korero. And this Saturday, a story from the book.