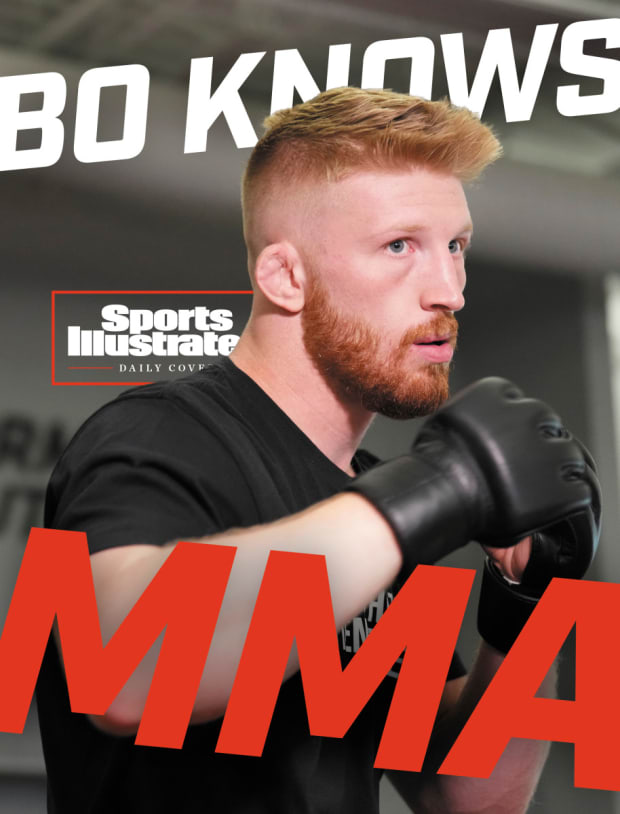

Bending his knees and extending his hands at waist level, Donovan Beard did what any sensible person in his position would do. When you’re in a steel cage, pitted against one of the most skilled and decorated wrestlers on the planet, it stands to reason that you would try to defend against the takedown.

Bo Nickal, though, has quickly gone from a top-shelf wrestler to a top-shelf mixed martial artist. Less than a minute into a middleweight fight last month on Dana White’s Contender Series—a Las Vegas–based showcase for promising fighters—Nickal rotated and torqued all of his 185 pounds. With Beard’s hands at half-mast, Nickal reared back and deployed a left hand that collided against Beard’s jaw. Beard collapsed like a sleeper sofa.

Nickal then transitioned slickly to the ground, wrapped his thick legs around Beard’s neck, sunk in a triangle choke and waited for Beard to tap out. Which he did, just 52 seconds after the fight started.

Chris Unger/Zuffa LLC/Getty Images

That the wrestler won without having to wrestle made for a vivid demonstration, the latest one, of how and why Nickal, at age 27, has quickly become the brightest ascending star in the UFC cosmos. He is the fair-haired boy (literally), a blond, amiable, measured—and, in a sport based in the U.S., staged mostly in U.S. venues, but short on American champions, pointedly, American—fighter who balances ferocity in the cage with a mature dignity on the civilized side of the fencing. As one hyperventilating headline fairly slobbered after this latest win, “Is Bo Nickal the LeBron James of MMA?”

Though they’ve all ended early and sensationally, this marked just the third pro fight of Nickal’s career. Still, the ref had barely finished hoisting his arm in triumph when Nickal was rewarded with the UFC equivalent of a Major League call-up. His main card assignation at UFC 282 was delayed because of a minor injury, but he now makes his breathlessly anticipated debut at UFC 285, this Saturday in Vegas.

Chris Unger/Zuffa LLC/Getty Images

Nickal embodies this truth: For all its plasma-rific, bone-rattling violence, mixed martial arts is ultimately a sport predicated on balance. It’s been 29 years since the first UFC fight card—they grow up fast, these combat sports—and cage-fighting has evolved into something totally, unrecognizably different from the original incarnation.

What began as an exercise in settling disputes in salons and saloons over which fighting discipline is superior, over whether Mike Tyson would kick Bruce Lee’s ass or vice versa … it’s now its own sport, and one that requires a full and diverse skill set. The boxer who can’t fight on the ground is akin to the baseball player who can’t hit the curveball. The judoka who struggles to land (or take) a punch is like the basketball player who can’t go to his right. “You’re only as good as the weakest part of your game,” Nickal, with characteristic matter-of-factness, said after a recent workout. “And everyone knows pretty early what that is. Of course they know your strength, too.”

Nickal’s strength is not just an open secret; it’s encased in American sports history. The son of a Division I college basketball player who also played for the Colorado Valkyries football team (mom) and a college football player who went on to become a wrestling coach (dad), Bo took to wrestling at a young age. “I was always zoom-focused,” he says. “I remember being seven, eight years old and wanting to be a state champion in high school, national champion in college, an Olympic gold medalist. I didn't just say it. These were goals, so I wrote ’em down.”

It was Kenneth Turan, the film critic and essayist, who once called wrestling “not so much a sport as a secret religion, a calling, a fanatical sect that captures your body and soul.” Nickal was always a faithful parishioner. He was never seduced by other, more social, less intense sports. The technique and all those positional tactics fed something in him. The conditioning that either nourishes or starves the will of wrestlers? He was all too happy to test the limits of his mind and body. “Training hard was never not fun for me,” he says. “Wrestling gives you this, like, total sense of self. I can’t describe it better than that.”

Bo was born in Rifle, Colo., but he, his parents and his three younger sisters moved often, careening around the West, as his father found different teaching and coaching jobs. But at each stop, Bo’s wrestling improved by another order of magnitude. By the time Nickal graduated high school in Allen, Texas, he was among the most decorated junior wrestlers in U.S. history, winning three state titles and finishing with a preposterous record of 183–7 with 131 pins.

Fred Vuich/Sports Illustrated

If Nickal is the UFC’s current flavor of the month, it recalls his status coming out of high school. One of the most prized wrestling recruits in recent memory, he chose to take his considerable talents to Penn State, a program coached by Cael Sanderson, perhaps the Greatest Wrestler of Them All, an Olympic gold medalist who went undefeated in his four years at Iowa State.

At State College, Nickal didn’t just meet expectations; he pinned them. Doing a fair approximation of his coach, in his four years at Penn State, Nickal won three individual national titles, two at 184 pounds. and the third at 197 pounds, the fulcrum of a team that itself won the national title all four years. Nickal’s career record at Penn State: an unholy 120–3. His senior season he won the Hodge Trophy, college wrestling’s equivalent of the Heisman. He was also named the 2019 Big Ten Male Athlete of the Year.

Sanderson noticed early on that the higher the stakes, the more the team needed points, the better Nickal wrestled. Sanderson also noticed something else: “He was a total team guy. So much that sometimes it hurt him. He’d be so engaged, he’d be watching his teammates and yelling for them, when he should have been warming up.”

For a generation of college wrestlers, the UFC was terrifically fortuitous, this opportunity that popped up out of nowhere. With little in the way of job prospects in conventional freestyle wrestling, suddenly a cohort of college mat men had a means of making a living, bringing their technique and toughness to bear. Randy Couture, Chuck Liddell, Tito Ortiz, Matt Hughes, the embattled Jon Jones (who headlines the 285 card) … all are OG UFC stars, who stumbled upon mixed martial arts after they were done with their college grappling.

In the case of Nickal, he always knew about the future potential opportunities inside the cage. When Nickal was a kid, the family would head to Buffalo Wild Wings and watch the biggest UFC cards. (Reflexively, he says, he would root for the fighters, like Couture, who came with wrestling backgrounds.) At Penn State, he saw recent wrestling alumni and older teammates make the jump. And the wrestling establishment that was initially wary of this brutal sport was starting to warm to MMA.

If the UFC benefited by having former All-American wrestlers—and college graduates—legitimizing cage-fighting as a bona fide sport, amateur wrestling benefited, too. Now, it was able to provide a career path for its most accomplished stars.

In college, Nickal didn’t want to contaminate his wrestling with MMA training. Before tapping out to the siren song of MMA, he wanted first to wring everything out of wrestling. After winning the NCAA title as a senior, he set his sights on qualifying for the Tokyo Olympics. COVID-19 waylaid his plans, though he did break up the monotony of the pandemic by marrying his college sweetheart, Maddie Holmberg—a three-time first-team All-American in track and field and a Big Ten champion in both the heptathlon and pentathlon—in December 2020. At the ’21 US Olympic Team trials, Nickal came achingly close but lost in the final round.

It was easier for him to administer last rites to his wrestling career when he knew a new sport awaited. Soon, he was inside a State College fighting gym, making the transition and learning new fighting skills. “As far as the learning curve, I would say it’s not the most difficult thing in the world to learn striking,” says Nickal. “And I think that jiujitsu comes naturally for me.”

The real adjustments? Some were cultural. Gone were the days of just bopping to the Penn State gym. Suddenly there were business matters and training sites to juggle: Nickal is now partner/co-owner in a private State College MMA gym and estimates he spends 10% of his training time at American Top Team, a prominent MMA gym in Coconut Creek, Fla. Moreover, “the total team guy” was now in this fiercely individual sport. Then there were (are?) the adjustments to rhythm. In college, Nickal would wrestle dozens of opponents a year and compete multiple times a week during the season. As an MMA fighter, he may get four fights a year, which still leaves months to funnel all that training into one night of competition.

For all the macho crosscurrents in wrestling, it’s never the intent to inflict pain on the opponents. You may impose your will on them. You may physically dominate them, even humiliate them. But you seldom leave them in need of stitches or a stretcher. Not so in MMA. “It’s a brutal sport,” marvels Sanderson, who, for all his unrivaled amateur wrestling excellence, never considered an MMA career. Nickal, too, had to adjust to entering the hurt business. “I don’t really care to hurt people or inflict pain,” he says. On the other hand, the high physical stakes—a risk-reward ratio heightened from that of wrestling—is part of the appeal. “I like the tactics, the strategy, having real consequences right away. You have to make a decision in a split second and you’re gonna reap the consequences immediately. That, to me, is what’s fun about [MMA].”

Hunter Martin/Getty Images

Then there is the art of selling a fight. In wrestling, he says, “You’re taught: Stay quiet, stay humble, don’t say anything and just go take care of business.” In the UFC, where fighters have brands to build and pay-per-view buys to gin up, self-promotion and fight promotion are occupational requirements. Here, too, Nickal has proven a fast study. He’s “strong on the mike,” as they say in MMA parlance, and not averse to talking some trash.

Last summer, after Nickal triumphed easily over Beard, Luke Rockhold, a UFC veteran, said: “Bo Nickal would get abused—absolutely abused. Wrestling is [different]. You can go so far until you run into the likes of me. But Bo, he’s an incredible character. The kid looks good, but he fought a f---ing bum.” Nickal clapped back on social media: “yo whatttt?!! Why is this clown even talking about me. ‘The likes of me’ he says. I’m dying.”

When Britain’s Darren Till, another veteran UFC fighter, said, unprovoked, that he wanted to fight Nickal and “drive the left hand through his skull,” Nickal responded thusly: “Man, Darren. Very, very cute. … I don’t know why you would say something like that, knowing what I could do to you.”

Nickal reckons it’s all another exercise in balance. He won’t be dying his hair the color of the rainbow or becoming a cartoon villain à la Conor McGregor or getting a look-at-me tattoo. But neither is he inclined to stay unseen and unheard. “I like to say what I think and be honest. I’m not out there to put people down and to try to tell everybody how good I am, because I think at the end of the day, my results will speak for themselves. But at the same time if somebody wants to talk, I’ll just come with facts. I think I’m gonna win every fight I go into, so I’m not afraid to say that.”

It’s not just the fighters who perform a balancing act. The UFC needs to hype fighters. A sport is nothing without a rotation of stars. But too much hype, and the UFC gives up the leverage that permits the organization to pay fighters scandalously low wages. At a time when there are few superstars in the UFC, though—and just two of the top 10 pound-for-pound fighters were born in the U.S., the UFC’s biggest market—executives can’t conceal their excitement for Nickal. Says UFC’s majordomo Dana White: “He’s one of the most credentialed wrestlers to ever compete in the UFC. And is already 3–0 in MMA, with his wins coming at a combined time of only 2:27. … I’m very excited to see how far this kid can go.”

Nickal isn’t, of course, the first prospect to get the bandwagon treatment—and the track record is decidedly mixed. In 2015 the UFC publicity engines revved up for Sage Northcut, a Texan with an impossibly muscled physique and the looks of a model. He started out 7–0 before losing two of his next three fights, requiring surgery after getting his face broken, and toggling between weight classes. Now 26, he hasn’t fought in more than three years. Upon the retirement of Ronda Rousey, Paige VanZant got the full marketing and promotion treatment. Alas, her social media following greatly outstripped her skills. At age 28, she’s out of the UFC and makes her living as a bare-knuckle fighter. Even Brock Lesnar, another elite college wrestler by the way, came to the UFC from WWE with great fanfare but wasn’t built to last.

Still, there’s an unmistakable sense that Nickal is no imposter, no counterfeit tough guy. He took his first pro fight in June and won in 33 seconds, starching his opponent with a one-punch knockout. Two months later, he fought again and won via submission in 62 seconds. Then came the Beard fight, the latest squirt of hype. It’s not simply that Nickal has dominated his first three fights. He has yet to take a punch. On Saturday he’ll face a more experienced but less gifted opponent in 34-year-old Jamie Pickett. Though Nickal is considerably favored, a win would prove he can hang in the big leagues.

That so many other established fighters trash Nickal is, in itself, revealing and validating. Even Khamzat Chimaev, an undefeated welterweight from Chechnya, has mentioned the appeal of fighting Nickal. Which is fine by the challenger. “What’s he going to do to me?” Nickal wondered aloud recently on a podcast. “Is he going to take me down? No. Is he going to submit me? No. Does he have a chance to knock me out? I guess, yeah, there’s a chance he knocks me out. But in reality, more than likely what will happen is I’m going to drag him down to the ground, do exactly what he does to all these strikers and I’m going to do it to him.”

In addition to his new UFC contract, Nickal supplemented his wages by betting on himself. “Even if I’m a heavy favorite and the odds are [bad] I’m not gonna lose, so it’s free money. That’s how I look at it.” Then in October, the UFC sent fighters a memo prohibiting them from betting on fights, including their own.

To Nickal, he’ll obey the letter of the law but not the spirit. “I’m betting on myself by going out there,” he says. “I’m here. I’m training. You see fighters who are undisciplined, who sign a contract to fight in a cage, but they don’t handle themselves as real professionals. I want to treat this like an NFL quarterback. I’m full 100 percent in, doing what I need to do to [reach] my goal—not just being a UFC fighter or, winning the belt. It’s being the undisputed pound-for-pound number one. And that’s what I’m gonna do. If you’re gonna go for something, why not try to go for the absolute pinnacle?”