Before Kurly Tlapoyawa became an archaeologist specializing in Mesoamerican civilizations, he was a young Mexican-American kid watching cartoons. He remembers, in particular, the first time he laid eyes on Namor the Sub-Mariner.

“It was on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends,” Tlapoyawa tells Inverse, recalling the 1981 animated series.

The episode, “7 Little Superheroes,” delivered Avengers: Endgame-levels of spectacle by gathering Spider-Man, Captain America, Doctor Strange, Firestar, Iceman, the obscure Shanna the She-Devil, and Namor into a single episode. The plot is a boilerplate ’80s cartoon — the group, stranded on an island, is picked off one by one by the Chameleon.

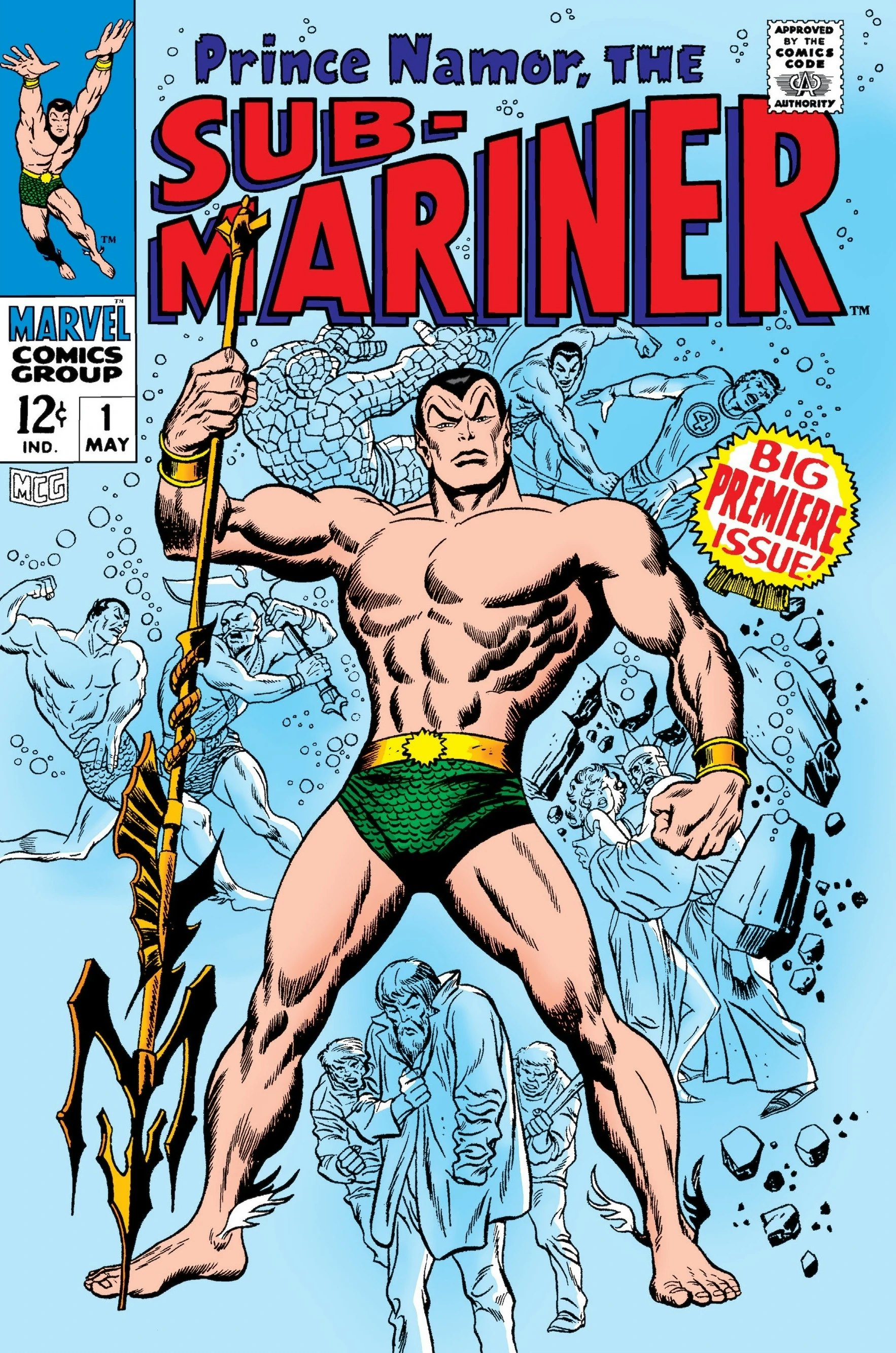

Namor the Sub-Mariner, the abrasive king of Atlantis, is one of Marvel’s earliest characters, having made his comic book debut in 1939. In contrast to DC’s conventionally handsome Aquaman, Namor’s features in the cartoon — all pointy ears and jet black widow’s peak — hinted at what he is: an outsider antihero who cooperates with the Avengers only when it’s in his favor.

“I was like, ‘That guy looks different,’” Tlapoyawa remembers. “He didn’t look like a white guy.” Namor’s otherness resonated through the screen to Tlapoyawa, who describes himself back then as “a young, angry Chicano” trying to figure out his place in the world. “If you look at the older comic books, it always talked about Namor and his war against the white man. That appealed to me as a Chicano kid — a non-white hero as one of the original Marvel heroes.”

It was kismet when the trailer for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever premiered at the 2022 San Diego Comic-Con. Today, Tlapoyawa is an archaeologist, author, and ethnohistorian whose work centers on Mesoamerica, a bubble region that encompasses ancient civilizations — including Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Toltec, and more indigenous peoples — spanning contemporary Mexico down to El Salvador and Honduras. The teaser for the Black Panther sequel revealed a new version of Namor, played by Mexican actor Tenoch Huerta, ruling a kingdom that ditches established Greek fantasy aesthetics for a distinct Mesoamerican flavor. Even the name “Atlantis” has been exchanged for a new one: in the film, Namor rules over “Talocan,” a riff on the Aztec paradise of Tlālōcān, one of the culture’s Thirteen Heavens, reserved for those who die watery deaths (like drowning).

As Tlapoyawa watched Huerta’s brown-skinned Namor don Aztec-style headdresses, he saw his interpretation of his favorite superhero canonized in the billion-dollar Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise. He also knew, from both his studies and as co-host of a podcast, Tales From Aztlantis, which debunks entrenched stereotypes about Mesoamerican civilizations, that the idea of Atlantis — the one in your head, of some apocryphal undersea kingdom file near “Bermuda Triangle” and “Sasquatch” in your memory banks, is thornier than most know. From its invention by a Greek philosopher to today, the myth and meaning of Atlantis have been borrowed and bastardized. And, when it comes to the kingdom’s relationship with the great civilizations of Mesoamerica, it is used to strip away their very-real achievements.

That’s where Tlapoyawa, at first excited about this new Namor, started to get nervous. “When I look at how my culture or the culture of Mesoamerica is represented in movies and TV shows,” he says, “a lot of things go sideways.”

The Real Truth About Atlantis

You may believe that Atlantis is a myth. It isn’t — technically.

“Atlantis is very specifically not a myth,” says David Anderson, an assistant professor of anthropological sciences at Radford University. Myths, he explains, are stories that “may or may not have happened in the past.” But Atlantis? “Atlantis has one source: Plato. It’s a parable by a philosopher to educate Athenians. It’s entirely a classic Greek story of hubris.” (The short version: Atlantis’ world-beating, super-powerful navy attacks Athens; Athens defeats it; Atlantis sinks into the ocean.)

The legend of Atlantis, then, is maybe best described as a fairy tale — one that, in the ensuing centuries, has inspired interpretations in everything from Disney cartoons to sci-fi television shows to comic books to crackpot culture-erasing, racism-inflected theories.

“It’s this bizarre, pseudo-historical reading that has no basis in reality.”

According to Anderson, Atlantis became a popular subject for fringe theories after the actual city of Troy was located in northwestern Turkey by German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in 1870. The excavation inspired a feverish search for other places told in Greek tales, and soon, Atlantis was on the docket. It became the next sought-after city with the 1882 publication of Atlantis: The Antediluvian World by U.S. congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly. The book posited Atlantis as the origins for ancient Egypt and Maya. Among his theories, Donnelly speculated that the Phoenician alphabet was derived from Atlanteans and later given to the Mayans.

Academically speaking, it’s baloney. “He’s pretty much making it up,” Anderson says. “When he’s writing in the 1870s, we didn’t know much about the archaeology of the world. People didn’t know a fair bit about Egypt. We knew jack about the ancient Maya. But he decides there are enough similarities from across the world that they must have a common origin in Atlantis.”

“It’s this bizarre, pseudo-historical reading that has no basis in reality, and ultimately, it’s racist,” Tlapoyawa says. “Any time you scratch pseudo-archaeology, under the surface, you’ll find racism sitting right there.”

Donnelly was not the first to pitch Plato’s creation as a theoretically real explanation for cultural transference. Almost a decade before Donnelly’s book, a British-American archaeologist and Freemason named Augustus Le Plongeon traveled with his wife, Alice Dixon, to the Yucatán, intending to connect the ancient Maya to Egypt and Atlantis. He believed the inverse of Donnelly: that the Mayans spread their culture, “and one of the first places it spread was Atlantis.”

“His idea was that the Yucatán was the cradle of civilization,” explains Tlapoyawa. A theory less based on cultural theft, but equally as wrong.

“You don’t need to embellish with b***s*** to make it interesting.”

So much of Mesoamerica has been subject to colonialism in which the people of the regions have their unique religions, histories, and technological achievements tirelessly filtered through a white European lens built on ancient Greek, Roman, and Christian texts. Colonial narratives frequently frame the presence of Europeans or space aliens as benevolent educators over so-called savages.

“It takes them decades to get their heads around the idea that there are continents with people they have never heard of,” Anderson says. Even Mesoamerican religions were hard for Europeans to fathom without reimagining it to their understanding.

“When the Spanish came, they thought of [central Mexican religions] as polytheistic,” Anderson says. But the only models for polytheism the priests had to reference were from Greece and Rome. “Spanish priests trying to chronicle [it all] tried to shove this Indigenous American belief system into a European system. And they’re different.”

Cribbing Culture

The likes of Donnelly and Le Plongeon inspired even more pseudo-intellectuals like Helena Blavatsky and Domingo Martinez Paredez, himself a Yucatec Mayan that Tlapoyawa says would “make up” Mesoamerican history. “He was one of the guys primarily responsible for mainstreaming the idea that the ancient Maya was somehow connected to Atlantis,” Tlapoyawa says of Paredez.

“In his work, I haven't been able to find him say the word ‘Atlantis.’ But he claims there was a lost civilization off the coast of the Yucatan that sank, and survivors taught the Maya their history and how to build pyramids. It’s basically the Atlantis story, just without the name.”

Collectively, the theories imply the real histories of indigenous Mesoamericans aren’t of importance and that made-up legends from white imaginations are the only explanation as to how these civilizations thrived at all.

“It robs the people of their own history,” Tlapoyawa says. “This idea there was some exchange, the Maya learning from the Atlanteans, instead of saying Indigenous people were smart enough to develop ideas on their own. The Maya have a legitimate, fascinating history. You don’t need to embellish with bullshit to make it interesting. They have their own accomplishments.”

“A Marvel movie is going to have more impact than Ancient Aliens.”

Interest in alleged connections between real American civilizations and fictional ones, like Atlantis, again surged in the 20th and 21st centuries. Paul Guinan, a comic book artist and writer behind the digital graphic novel Aztec Empire, points to the 1968 publication of Chariots of the Gods (a German book proposing that all ancient civilizations received their religions and technology from aliens) and TV shows like the History Channel’s Ancient Aliens, for perpetuating “baseless theories.”

“Creating a fantasy with Mesoamerican elements isn’t inherently racist,” Guinan explains via email. “It is definitely racist, however, when Mesoamerican cultures are depicted as needing outside help to achieve sophistication. That kind of depiction robs whole cultures of credit for their own accomplishments. Ancient Aliens is among the worst examples of this take.”

It’s into this fraught centuries-long relationship between actual, documented Mesoamerican history and the fictitious, often problematic, “story” of Atlantis, that Black Panther: Wakanda Forever wades.

Marvel Goes to Atlantis

We won’t know exactly how Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and its creators — particularly director Ryan Coogler, co-writer Joe Robert Cole, and Marvel Studios’ creatively-involved president Kevin Feige — will add to the complicated canon of Atlantis until the film arrives in theaters on November 11. (Requests to interview Marvel for this story were denied.) But by building Aztec influences into Namor and his kingdom, they’ve accepted some obligation to show a studied reverence for Mesoamerican culture.

“It leaves me nervous,” says Anderson, who is a Marvel fan. Beyond the racist landmines in the Mesoamerican connection to Atlantis, he adds that inaccuracies in any artistic blending of Aztec and Mayan designs would be offensive, too.

“My biggest concern would be if the MCU depicted Mesomaerican-style Atlantis as a savage, bloodthirsty culture,” Guinan writes to Inverse. “That would just be recycling tired stereotypes.”

What the best version of Black Panther’s Atlantis (which isn’t named “Atlantis”) should even look like, though, no one’s in complete agreement.

Everything seen in the movie’s promotional materials, from Namor’s headdress (inspired by the Jaguar deity Tepēyōllōtl) to artistic murals – which both Tlapoyawa and Anderson say are just gibberish – inspires mixed emotions. Even switching the name Atlantis to Talocan causes divisive feelings. Anderson’s glad they’re leaving that Euro-centric version off the screen; Tlapoyawa wishes a real Aztec word would have been used.

“[Nahuatl, the Aztec language] is a living language, one of 38 living Indigenous languages in Mexico,” he says. “Why didn’t they use a real word when we have an actual word that means ‘the place of water?’”

There’s more at stake than just the details of Marvel’s fantastical world-building. A movie like Wakanda Forever isn’t just a movie but a shared cultural experience that can influence thinking for decades to come. How Wakanda Forever succeeds in its artistic ambitions can be mutually exclusive to how well it references — and navigates — the ill-informed pseudo-archeology that has also historically alienated real human beings.

“They’re going to embed in mainstream America how people perceive ancient Mesoamerica,” warns Tlapoyawa. “Marvel’s an institution. A Marvel movie is definitely going to have more impact than Ancient Aliens.”

“Wakanda and Atlantis are fictional, but Africa and Mesoamerica are real,” Tlapoyawa adds. “In the real world, negative or positive, it’s going to have consequences, how much thought they put into it.”

The Inverse SUPERHERO ISSUE challenges the most dominant idea in our culture today.