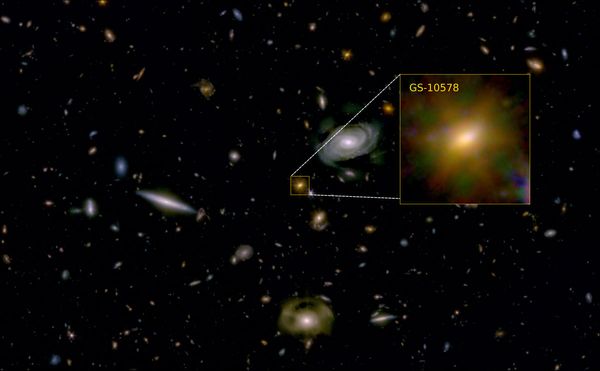

For a galaxy at its age, Pablo's Galaxy is massive. Formed during an early period in the universe's history and officially known as GS-10578, Pablo's Galaxy received its nickname from a scientist who observed it in detail and noted its immense size: Its total mass is about 200 billion times the mass of our Sun.

Yet like a spiraling whirlpool, a black hole is currently removing so much gas from Pablo's Galaxy that it can no longer normally form stars. Thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), University of Cambridge researchers led a study in the journal Nature Astronomy revealing the exact amount of gas being uncontrollably pulled into the celestial abyss by the black hole's gravity.

"Even though everyone was expecting black holes to starve galaxies by heating or removing gas, measurements showed that the amount of gas we could see being removed was simply not enough," Francesco D'Eugenio, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge's Kavli Institute for Cosmology, told Salon. "But before JWST, we could only see the hot, thin gas that shines most brightly. It turns out most of the gas being removed may be colder and harder to see."

D'Eugenio added, "JWST is so extraordinarily sensitive that we can observe much colder gas than with other telescopes." Detecting gases that had previously been too dark for them to identify and study, the scientists "measured how much gas is being removed from the galaxy, and how fast it is moving; the numbers show clearly that the amount of gas is sufficient to disrupt the normal star-forming activity of this galaxy."

In explaining a great deal about galaxy formation, the new study also raises provocative questions. Cosmologists believe the early universe was teeming with galaxies — perhaps even some filled with alien life. But clearly it didn't take long (on cosmic timescales, at least) for some galaxies to reach the end of their life. Pablo's Galaxy stands out for being dormant despite its large size and advanced age.

“In the early universe, most galaxies are forming lots of stars, so it’s interesting to see such a massive dead galaxy at this period in time,” co-author Professor Roberto Maiolino, also from the Kavli Institute for Cosmology, said in a press statement. “If it had enough time to get to this massive size, whatever process that stopped star formation likely happened relatively quickly.”

In terms of the quantity of the gas being expelled, scientists ascertained that ionised- and neutral-gas outflows measured by their equipment ultimately reached "0.14–2.9 and 30–100 solar mass per year, respectively."

If this much solar mass in a young universe was annually being forever lost into the gaping maw of a black hole, it would be less unusual. Yet according to D'Eugenio, "galaxies as massive as this one grow by attracting gas from a vast reservoir that surrounds them." This means that, especially for a galaxy formed early in the universe's history, gas would continuously fall into the galaxy, coil down and form large numbers of stars, which humans can detect even from thousands of lightyears away. "In these early epochs, the amount of gas around galaxies is so large that continuous star formation is the norm. But in this galaxy this process is not happening; there is a spanner in the cogs of the star-forming 'machinery.'"

The culprit is the central supermassive black hole, not unlike the one at the center of most galaxies, including our own.

"The [energy released from gas falling into the] the supermassive black hole is removing large amounts of gas very fast from the galaxy," D'Eugenio explained. "Without this gas, no new stars can be formed, so this galaxy is losing the `shine' of young and bright stars, and has already started it's long history of fading."

Scientists are regularly uncovering new insights into the violent nature of black holes. A 2023 study in The Astrophysical Journal revealed that black holes which suck up gases — forming what's known as accretion disks — do so in a manner of mere months, which is extremely rapid on an interstellar timescale, as well as 10 to 100 times faster than scientists previously believed.

The researchers led by Northwestern University's Nick Kaaz, a graduate student in astronomy, used computer simulations to determine that the black hole causes rotations which warp the accretion disk in such a way that the gas actually starts caving in on itself. This drives the mass into the black hole at an even faster rate, strengthening the gravitational pull as the gas is continuously slurped into the black hole's center. Eventually the entire accretion disk is torn in half, with the black hole first consuming the inner disc and then the outer one.

Coming on the heels of that research, the study into Pablo's Galaxy can help transform our understanding of how galaxies and stars are both formed and destroyed. Yet aspects of the story remain enigmatic, even in the case of Pablo's Galaxy.

"The stars in this galaxy are going around in circles about the center of the galaxy, which suggests that this galaxy did not undergo any major cataclysmic event (like crashing with another big galaxy) which could disrupt the ordered motion of its stars," D'Eugenio said.